My late grandmother, a farmer’s wife in the agricultural heartland of Thessaly, had a generic term for wholemeal bread: skylopsomo, which translates as “dog bread.” In her household, as in most households at the time, bread for humans was made from refined white wheat flour. The bran from processing the grain was baked into loaves and fed to the farm dogs. I can picture my grandmother crossing herself and chuckling wryly at the thought of what is sold as bread for human consumption these days, and the premium that consumers are prepared to pay for it.

Over the past decade, the seeds of a small revolution have been sown: Greece has seen the revival of ancient food crops as modern “superfoods.” Plants once derided as famine food or relegated to animal feed now line the shelves of health-food stores and upmarket delicatessens, to meet an increasing demand for special diets, nutritional supplements and more adventurous gastronomic experiences.

Dotted all around our ancestral village, across the Thessalian plain and up into the surrounding hills are clearly visible mounds, which the locals call magoules (cheeks). They are the layered remains of generations of habitation by the very first Greek farmers, dating back as early as 9,000 years ago in the Neolithic period. These early farmers cultivated the ancient varieties of today’s grains; crops that were first domesticated in the Near East from wild grasses, 2,000 years earlier. Emmer wheat, whose scientific name is Triticum dicoccum, is one of the oldest domesticated grains, together with einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum) and barley. To this family was later added spelt wheat, Triticum spelta; together they formed the backbone of the early farmers’ diet. Neolithic cereals yielded meager volumes by today’s standards, producing smaller seeds encased in a hard husk, which required hours of extra labor to remove after threshing, and even further effort to grind. But the grains were also hardier, more resistant to pests and weather, and more nutritionally complex than their modern descendants.

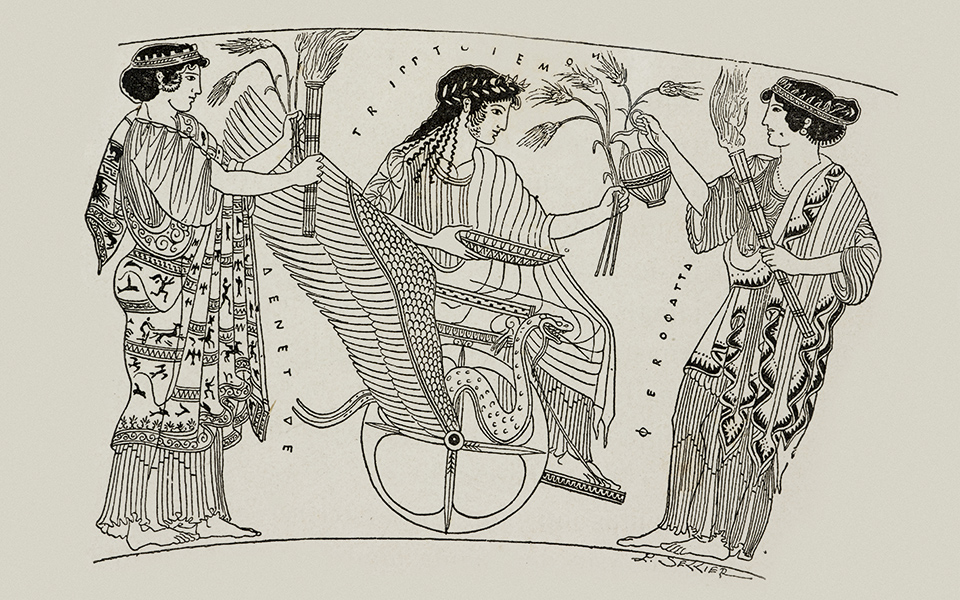

In classical Greek literature, we find references to a grain called zea or zeia (as distinct from the more common sitos for wheat) which may hark back to these earlier wheat varieties. For Homer, zea was a byword for fertility: the epithet zeidoros, meaning “zea-gifting”, is used in the Iliad to describe fertile land. However, it is not entirely clear whether zea was grown for human or animal consumption. Certainly Herodotus thought it worth mentioning in his Histories that the exotic Egyptians preferred zea to wheat or barley. It is also suggested, based on medieval texts, that the grain gave its name to the Piraeus harbor of Zea; however, more recent investigations have shown that in classical times, Zea was a naval base for Athens’s fearsome fleet of trireme warships, rather than a grain port.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Despite the ambiguities of language, the name zea with its classical connotations has become widely adopted in modern times. By the classical period, the archaeological evidence suggests that the ancestral wheat varieties had been mostly displaced by barley, and eventually by durum and bread wheat. By modern times, zea was all but unknown in Greece. An urban myth holds that its cultivation was banned in the 1930s, for fear of undercutting the price of grain imports, or, in a more lurid version, in a bid to keep the Greeks docile by depriving them of key nutrients. The reality is probably more pedestrian. Modern wheat varieties are much better suited to meeting modern mass demand, as they have been hybridized over the centuries to produce high yields, and are much easier to process by mechanical means. The main holdout for emmer wheat in modern times is Italy, where it is known as farro; the canny Tuscans have protected the grain as a regional specialty (Indicazione Geografica Protetta) since 1996. The name farro is used in Italy colloquially to refer to einkorn and spelt as well as emmer, often causing confusion among grain purists. Like zea, it is a useful shorthand for rustic grain varieties that have more in common with one another than with modern hybrids.

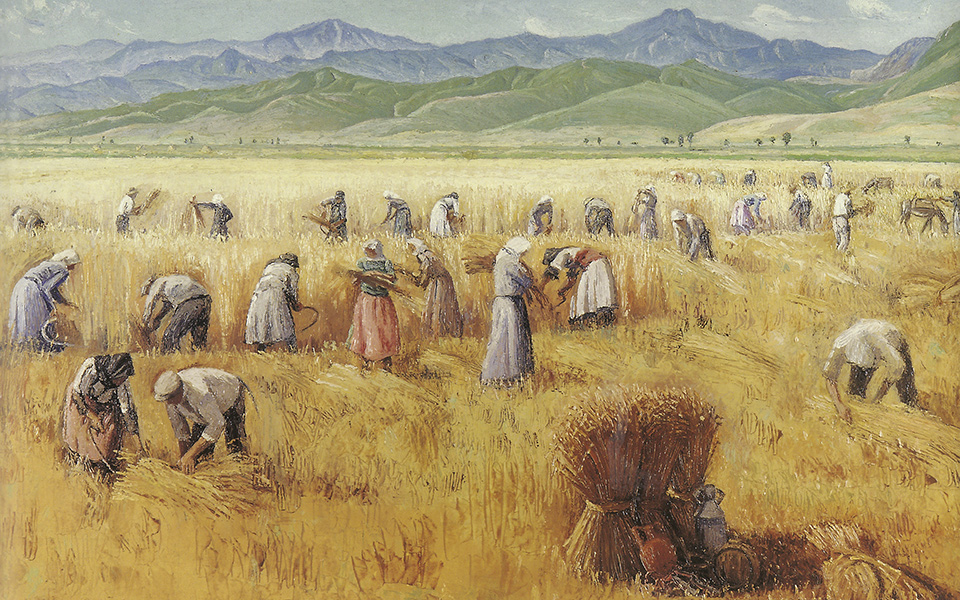

Within the last decade, just a few kilometers along the highway in both directions from our ancestral village, on land overlooked by the Neolithic magoules, a small group of entrepreneurial farmers have decided to reject modern high-yield wheat varieties and cash crops such as cotton and sugar-beet, which dominate the fertile plains, in favor of these ancestral grains. While some producers have opted to use certified Italian farro seed, marketed in Greece as Dikokko Sitari, at least one farmer claims to be using old grain curated by his family in Thessaly, marketed as zea. Their products can now be found quite widely in health food stores and Greek specialty delis, and are making their way into supermarkets and neighborhood bakeries as well.

The whole grains can be used in soups, stews and risottos instead of rice or pasta, while the flour can be baked into bread and cookies, and dried pasta made from the flour is proving particularly popular. Zea grains have a very distinctive nutty flavor, while bread and pasta produced from them have a pleasantly chewy consistency but are lighter and more elegant in texture than wholewheat alternatives.

In addition to providing a more adventurous gastronomic experience, proponents of emmer in particular note that it is low in gluten (though not gluten-free), twice as rich in dietary fiber as ordinary wheat, and high in the amino acid lysine, which improves digestibility. It is therefore suitable for diabetics, as well as people with mild digestive disorders (though not for sufferers from severe wheat allergies). It is also rich in vitamins A, B, C and E and magnesium.

“Zea grains have a very distinctive nutty flavor, while bread and pasta produced from them have a pleasantly chewy consistency but are lighter and more elegant in texture than whole wheat alternatives.”

“I would say that it’s like eating a dietary supplement,” says Vincenzo, an Italian transplant who, together with his Greek wife, has spent the last 20 years running Aloe, a local health food store in the residential Athenian neighborhood of Ilissia. “People these days are being more careful about what they eat, even though there is less in their pocket. I have new customers coming to us and asking for these products all the time, particularly young mothers.”

The revival of ancient grains is part of a global phenomenon, spurred by a growing recognition of the health contribution of dietary fiber, the enduring popularity of the Mediterranean diet and the search for new gastronomic experiences. There is also a burgeoning demand for gluten-free, whole foods and other alternatives to processed wheat, initially to cater to sufferers from medical conditions such as celiac disease, but increasingly to meet demand for alternative diets as a lifestyle choice (the global market for gluten-free food alone was valued in 2011 at $1.6 billion). In Greece itself, greater health-consciousness and a return to traditional ingredients and recipes and locally-grown crops has created a flourishing domestic market in the teeth of the recession. Indeed, as Greeks turn to their native soil and traditions to restore their national pride, and a new generation of producers look with fresh eyes on neglected opportunities, alternative food crops may be among the few economic sectors benefiting from the crisis. There is clearly room for growth in the home market, as German spelt – marketed as Dinkel – still takes up considerable shelf space alongside the native products, while global demand might eventually provide an export market.

Gusto di Grecia, a delicatessen specializing in traditional Greek foods from small producers in the upmarket neighborhood of Kolonaki, carries several lines of zea and Dikokko products. “We see lots of demand for whole grains from people with special dietary requirements, but our mission with all our products since starting out has been to identify small producers across Greece,” says sales manager Katerina. “There’s a lot of activity in the countryside, often by young people, reviving traditional foodstuffs and bringing them to market.”

For the farmers, this growing appetite for ancient grains presents a clear opportunity. Emmer and its sisters are likely to remain a specialty or “premium” product, as the prices are considerably higher than for ordinary wheat products: according to the producers, grains fetch up to two and a half times the price of wheat in wholesale terms, and the gap widens for processed products. Much of the price differential is due to the lower yields, greater wastage (those tough hulls) and higher processing costs compared to industrially grown wheat, so not all of it goes to the farmers as profit. However, the ancestral wheat varieties can grow in poorer quality rocky soil, thrive in hilly terrain up to 1,500m elevation, do not need irrigation and require fewer fertilizers and pesticides because of their naturally higher resistance to pests and common diseases. Thanks to their rugged, undemanding character, they allow farmers to cultivate land that would otherwise lie fallow. I’m sure my grandmother, who by all accounts held the purse strings in the household, would see the benefit in that.

MORE ANCIENT SUPERFOODS

• Other traditional crops are finding a new lease of life as modern “superfoods,” too. For modern metropolitan Greeks, eating acorns has long been a metaphor for desperation or backwardness, but on the Aegean island of Kea, a resident American used the Kickstarter online crowd-funding platform to fund a revival of the local wild acorn harvest. The acorns are used to produce nutrient-rich gluten-free flour and baked goods which are exported worldwide. The harvest itself forms the focus of a growing agritourism trade, for visitors looking for something more than a beach holiday. (Read more: www.iloveacorns.com)

• Stamnagathi, a wild spiny chicory rich in fiber, vitamins and antioxidants, traditionally popular in Crete for both raw and cooked salads, is now systematically cultivated for the Greek market and is also exported to France.

• Sea-buckthorn (Hippophae L.) is a berry which was mentioned by Dioscurides, the “father of pharmacology,” and other ancient authors as a medicinal plant. Its scientific name, derived from ancient Greek, translates as “shiny horse” – it is credited with keeping the horses in Alexander the Great’s cavalry healthy and bright-coated. Over the last decade, it began being systematically cultivated in Greece, with support from the government. The berries are made into premium fruit juice for the Northern European market; it is also used in a variety of food supplements, skin treatments and cosmetics.