“In the early ’70s, when I was a college student, I wanted to find a remote place, an island. There was a dot then on the map named ‘Donoussa.’ It took me 32 hours back then to reach the island, on a non-commercial ship.”

This is, more or less, the story of the first visit to that small Cycladic island in 1972 of Yiorgos Kolozis, one of the directors and the titular character of the documentary “Yiorgos of Kedros,” filmed on location on Donoussa. The work was originally scheduled to be premiered this March at the Thessaloniki Documentary Festival, which was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Friends of mine stirred my interest in the film, telling me good things about the island and even better things about Kolozis who, unfortunately, passed away in 2009 before completing his documentary – his son, Yiannis, took over directorial duties after his father’s death. As I really wanted to watch the film, a friend put me in contact with Yiannis, and the next thing I knew, I was laying on my couch at home, ready to travel in spirit to somewhere in the Cyclades.

Watching it, I soon realized that this was not your typical travel documentary; rather, it was a study on the passage of time, on the concept of memory, and on the very act of traveling, all quite fitting subjects in times when all we can do is reflect on our past travels and look forward to potential future ones.

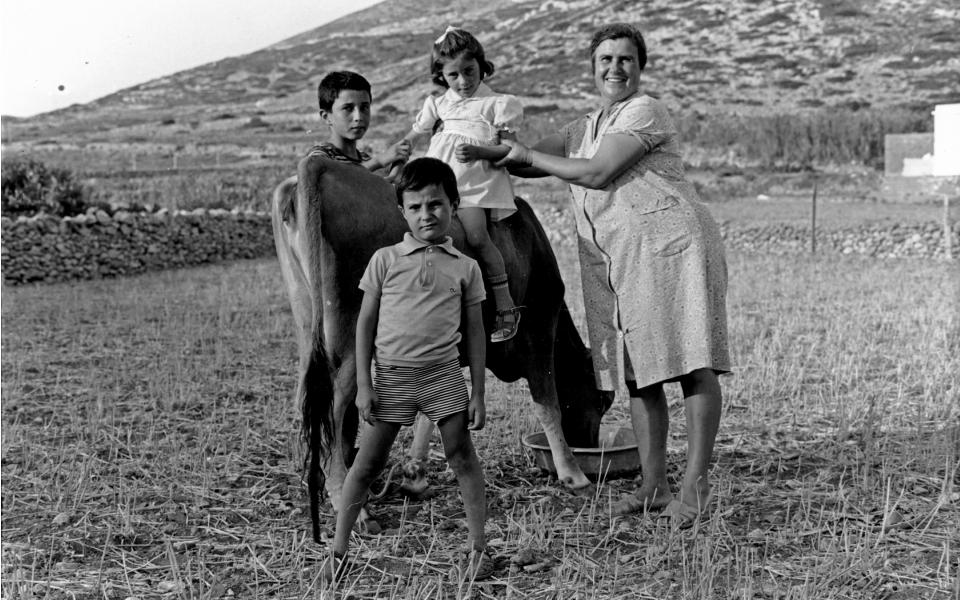

“When I arrived, it was practically a deserted island. There was no electricity, there was no port, there was nothing,” recounts Yiorgos, who comes to be known by the locals as “Yiorgos of Kedros,” having chosen to live alone in a tent on the then-empty beach of Kedros (meaning “Cedar”). From the very beginning, he felt such love for the island and its inhabitants that he returned every summer until 1978, capturing both landscapes and people with his analog video camera (using different film formats – standard 8mm, super 8mm and 16mm) and his still-shot camera.

“Traveling is not only about nature and landscapes; it is the people who play the biggest role. You travel, you meet someone, you speak to them, you exchange words, you hear sounds: that’s the magic of traveling,” Yiorgos Kolozis declares.

In 1999, after an absence of almost 30 years, Kolozis went back to Donoussa for another recording session – this time with digital cameras – only to find that a lot had changed on the island, and that many of the people he had met during the 1970s had passed away, while others were well into old age. Scenes in which the “survivors” look at black-and-white photographs of themselves and relatives, snapshots that Yiorgos had printed to give them as gifts, are highly emotionally charged. “Mitso, come look at your face. Come see how nice you look,” an old lady shouts to her husband as she sees a picture of him as a younger man.

It was during this trip that Kolozis decided that he would eventually turn all his footage into a documentary. He went back to the island in 2007 with his son, for what they both thought would be the final shoots. Unfortunately, Yiorgos’ untimely death in 2009 did not allow him to complete his film, but his son Yiannis took over the production, returning to the island numerous times to try and relive his father’s island experience from its beginning in order to understand “the equation comprising time, place, human consciousness and feelings, resulting in what we call memories,” as he wrote in a crowd-funding campaign he launched in 2018 on indiegogo.com to gather the money needed to complete the film.

“I went back to the same places and the same people, over and over again. It all seemed the same, although it was completely different. It was different because time changes things, and memories transform,” says Yiannis, who takes over the role of narrator halfway through the documentary in an account that, at some point, stops being linear. The story evolves into an emotional mix of shots ranging from those taken in the ’70s to others from 1999 and contemporary ones as well: the past becomes present, and objective time loses all meaning.

In the midst of a nearly hypnotic state caused by the swift changes in formats and shots, I heard Yiorgos repeating something for the third time in the documentary: “All in all, I like to come back.” It made me think that, in the end, the film actually dealt with the act of coming back – what is memory, if not a return in space and time? And how timely is the concept of return when we have been immobilized, when the only way we can look is back?

Perhaps, when all this is over, instead of constantly dreaming about new travels and constantly seeking new landscapes, it might make more sense to go back to places we know well, and rediscover them from the beginning: we might re-encounter our true selves somewhere along the way.