The original Byzantines, inhabitants of the colony of Byzantion, founded by Greek settlers from Megara, are considered to be the foremost oenophiles and inebriates of the ancient world. They loved wine so much that they actually lived in the taverns and let out their homes (together with their wives) to merchants and foreigners passing through the city. Men of business to the core, they were the opposite of warlike. It was said they could not bear the sound of the war trumpet, even in their dreams, as their ears were accustomed to the sound of flutes at drinking parties. On one occasion, when they were at war, their general, Leonides, ordered the wine dealers to set up tents on the city walls; only then did they stop abandoning their posts to go off drinking.

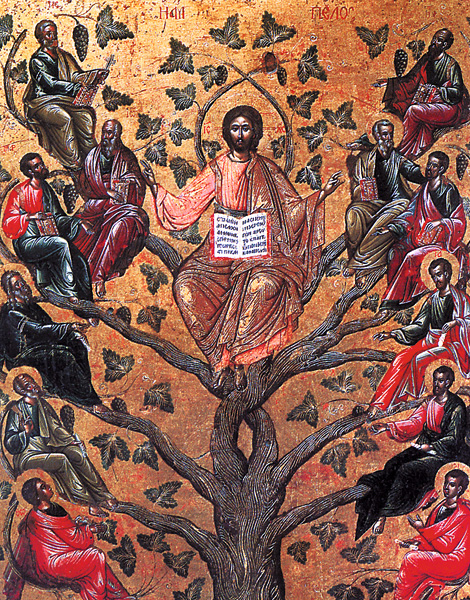

Reflective of such accounts, the proverb that “Byzantium conquers all with its wine” was handed down – as a nod to wine appreciation – to the successor city of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire (323-1453). The Byzantines saw their empire as a vineyard and the rulers as grapevines, but also as kraters of wisdom in which the new krasis was created, the new mix that would eventually give a new name to wine, krasin. The vine and wine, Dionysian symbols of culture, sybaritic indulgence and authority were mixed with the biblical concept of power and the spread of the chosen people of Israel (seen as a grapevine) to the ends of the earth, as well as with that of Christ as the true vine and of his disciples as branches, who went forth to change the world with the word of God. Such symbols were adopted and used in the ecumenical vision and imperial ideology of Byzantium. The expansion of the empire and intermarriage with foreign princesses also found apt symbolism in the transplanting of vines and in their offshoots.

In medieval times, both Constantinople and the empire itself were viewed as a place where wine flowed freely. Northern Europeans gave Constantinople the nickname Winbourg, the City of Wine. And they had good reason to do so. To both the Muslim world, where wine was generally forbidden, and to the peoples of northern Europe, the Christian empire was the preeminent land for the growing of vines and the production and consumption of wine. Between the 5th and 7th centuries, the trade or distribution of wine from Byzantium, to satisfy the needs of the army and local inhabitants alike, had spread to Numidia, Nubia, Ethiopia, the Caucasus, the Crimean hinterland, Ireland and England. The same pattern appeared later (10th-12th centuries) among the newly converted Christians along the Volga and as far as Novgorod and Scandinavia. The Slavs, Varangians and Anglo-Saxons in particular, but also the steppe peoples subsquent to their Christianization, saw Byzantium as a country full of vineyards, a place where they could purchase wine and oil. Indeed, the conversion to Christianity of Bulgarians, Serbs, Russians, Caucasians and many others by Byzantine missionaries inevitably brought them into closer contact with wine on account of the Eucharist – one more important Byzantine contribution to the dissemination of wine culture. Thus, in any center of Christian worship, a vine would necessarily be planted to provide wine for Holy Communion.

The vine and wine, Dionysian symbols of culture, sybaritic indulgence and authority, were mixed with the biblical concept of power and the spread of the chosen people of Israel.

© VisualHellas.gr

The contribution of monasteries and the church in general was a catalyst, therefore, not only for the dissemination and “Christianization” of wine culture, but also for the evolution of the beverage and the symposia (drinking parties) of the ancient world into more morally acceptable forms of wine consumption. Of course, the orgiastic Dionysus never disappeared. Despite sermons and condemnations of the oenophilic lifestyle by the church, Bacchic rites continued, as did prostitution, with wine consumption rife among soldiers and farmers, in ports, at trading posts, in fortress-cities, at inns, drinking dens and taverns, even in monasteries. There were also many instances of Dionysus using his charm to take over the imperial palaces, resulting in a series of famously drunkard emperors.

But emperors were not the only sots; monasteries were home to the most iconic drunks of the Byzantine period, namely monks. The extreme monastic notion of the need to avoid the pleasures of wine, merriment and intoxication, contrasted sharply with the reality of inebriate monks and left the supposed ascetics exposed to all manner of mockery, especially in the 10th and 11th centuries. It was during this period that wine appreciation found new favor – particularly among the elite and the upcoming middle classes – and also when the literary figure (as an anthropological type) of the Krasopateras (wine-bibbing monk) was created, the equivalent of medieval western Europe’s pater vinosus. It was also during the Byzantine period that a symbolic correspondence between sea and wine and between ship and cup was first suggested or magnified through use of ancient literary traditions and notions of drowning in wine or the sea, or of the harvest as war and love. These were themes that were to be embraced by neo-Hellenism in order to give a seal of approval to its wine-drinking lifestyle. In the same period (11th-12th centuries) important monasteries on Mount Athos, as well as the Metropolis of Thessaloniki, owned a large number of vineyards in Halkidiki and throughout Macedonia. Indeed, the Great Lavra monastery was systematically engaged in the wine trade with Constantinople and sought special tax treatment.

Celebrated Byzantine Wines

A number of Byzantine provinces were renowned for their sweet, aromatic wines: Bithynia, in particular. Sweet wines made from different varieties were reputed to be produced there, while physicians referred to their medicinal properties. Many celebrated wines were also produced in the early Byzantine period in Syria and Palestine, in reconquered Carthage, in Egypt, on the Aegean islands, in the Peloponnese and in Italy. One account describes a scene during the reign of Justin II (565-574) in which the emperor and his wife, Sophia, look out at the ships in the Bosporus and the Sea of Marmara (historically Propontis) transporting wine to Constantinople from Gaza, Egypt, Italy, the Peloponnese, Mytilene, Chios and Rhodes.

In the years that followed the reigns of Justinian I (527-565) and Justin II – with Avaro-Slavic invasions that lead to the destruction of vine crops in the Balkans and Greece, as well as Arab incursions that resulted in the loss of Syria, Palestine, Egypt and in a disruption of Mediteranean trade – Bithynia became the main supplier of wines to the Byzantine capital. Besides the prevalent inexpensive, sour, watery wines, reeking of resin, originating from Philippopolis to Attica, there were also “precious,” delicate, sweet and fragrant wines from Bithynia, fine wine from Nicaea and flowery Anthosmias from Cyzicus. These were old wines from the imperial estates, made from sun-dried grapes. This type of imperial Bithynian wine is thought to be associated with a new wine known as Malmsey, or Malvasia (as it was known in Italy and the Iberian Peninsula, after Monemvasia). First mentioned in 1214, it was reportedly offered to and consumed by the Latin conquerors in front of Hagia Sophia, along with wines from Chios and Lesbos. Monemvasian-type wines from the Peloponnese, Crete and the Aegean islands now came to prevail also in Constantinople at the center of trade rivalry.

A number of Byzantine provinces were renowned for their sweet, aromatic wines: Bithynia, in particular.

Along the shores of the Bosporus, the struggle between the Italian maritime republics over free movement of goods in Byzantine ports, especially wine, accompanied by their demands for tax exemptions (12th-14th centuries), meant that all the oenophile Byzantines could hear was war trumpets. But the Byzantines themselves no longer had to set up wine shops on the city walls. They now had protection and commercial power in the form of operating licenses for inns and wine shops, where political games of power were played out, altering the fates of mariners, merchants and empires.

Against this background, the provinces around the Sea of Marmara and the Bosporus, with assistance from the wine-growing regions of the Aegean, influenced and steadily shaped Byzantine wine culture for approximately 1,000 years, even during the Ottoman period. Bithynia supplied wine to the Byzantine capital, but also received visitors from the city. In late Byzantine and post-Byzantine times, despite periodic declines in wine-growing, the region continued to produce its acclaimed wines. In the 14th and 15th centuries, wines from Cyzicus and Trigleia (present-day Tirilye), but also from Thrace, the Peloponnese, the Aegean islands and Crete, reached Constantinople or passed through the Bosporus strait to reach the peoples of the Black Sea.

Towards the end of the medieval period, when the empire fell first to the Crusaders and then to the Ottoman Turks, there came, shortly before the New World was discovered, what is undoubtedly Byzantium’s most important contribution to the wine map of new Europe. It was at this time that the chapters concerning vine cultivation and wine-making by Cassianus Bassus in the Geoponica were sent to western Europe to be translated and used by agriculturists. Also transferred were actual vines, wines and, above all, precious know-how on the production of what was the pre-eminent wine during the entire medieval and Renaissance periods – Malvasia. Sweet wines from Cyprus, especially the famous Commandaria – as well as the Malvasia and Athiri wines from Crete, the Aegean islands and the Peloponnese; the wine of Trigleia and Ganos, produced by Greeks of the Sea of Marmara and Thrace; and various other Muscat wines – flooded the European market as far as Scandinavia. The West appreciated, sought out and finally played a major role in establishing both in Europe and around the world a unique wine, Malmsey.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ilias Anagnostakis is research director at the National Hellenic Research Foundation’s Institute of Historical Research.