The French Painter Who Found his Island Muse...

Igor Borisov turned Kimolos into his...

© Maya Tsoclis

Do you see this one over here? It’s feeling sad,” the farmer informs me, kneeling over his as-yet-unripe watermelons. With coarse hands, he carefully tends to the earth around the weak plant, uprooting the weeds.

“And the one next to it – the one that’s in good shape – what’s that, Mr Tzortzis?” I ask him. “Ah, that one is happy, can’t you see?” he answers, full of enthusiasm.

It’s morning in the meadow around Komi, one of the very few flat areas on the whole island of Tinos. The north wind just manages to slip through the slender canes that demarcate property boundaries, safeguard crops, and create a wondrous canvas of geometric shapes that only the birds flying overhead can truly appreciate.

There are vegetables and greens here, artichokes just over there, and potatoes a bit further down. There are also lemon trees that emit their intoxicating scent every spring, a heady perfume that wafts down narrow, labyrinthine dirt roads and into country churches like the one near here, dedicated to Aghios Isidoros, the patron saint of farmers.

In some fields, solitary pensioners – with time now on their side – carefully cultivate a kitchen garden to supply the family dinner table and those of a few friends. In other sections, the farming is done on a larger scale, and by younger hands; produce from these tracts is usually destined for the island’s street market, or even perhaps the markets in Athens.

At one of the artichoke farms in the village of Komi, Ms Rafiopoulou carefully harvests the fruit of her family’s labors.

© Maya Tsoclis

Mr Christos from Skalado grows all sorts of produce in his garden, which his family processes and sells.

© Maya Tsoclis

On the surrounding slopes, stockbreeders call out the typically Tiniot “e-e-e-e-la” (“Come!”) summons to their cows, inviting them to get milked, and the animals descend grandly from crags and dry-stone terraces in search of relief.

The karikia (special containers used for storing fresh milk) are put in the shade to await the arrival of the truck from the cheese-making facility of the Agricultural Cooperative of Tinos. Once they’re loaded onto the vehicle, they’ll travel down the asphalt road that runs next to the meadow, below the section where the cows graze, a road that today, seems to link the present with the past.

This road also happens to lead to the impressive sandy beach of Kolymbithra and to one of the nicest (according to The Guardian) beach bars in all of Greece. At Tinos Surf Lessons and Beach Bar, no structure is permanent. You’d swear the umbrellas were blown there by the summer winds, and that the bar itself – housed in a little Volkswagen van – is just passing through.

Nonetheless, this has become a gathering spot for a new group of visitors, people who ride the waves, care about the environment, meditate, love the arts, and would rather adopt the livestock they see on the island as pets than consume them as food. And while they might gladly take part in the local church festivals, these folks have definitely not come to the island on a religious pilgrimage.

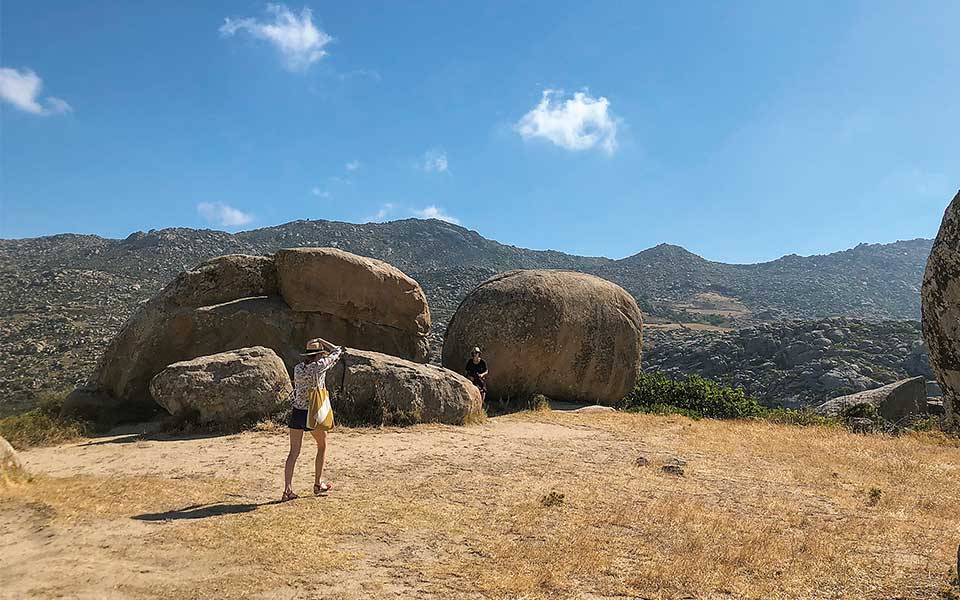

Granite boulders near the village of Volax, on one of the island’s signposted hiking trails.

© Maya Tsoclis

And yet, for Greeks, it’s as a pilgrimage destination that Tinos is most famous. For decades, Tinos has been associated with piety and supplication. And, let us praise the Lord for that! The flow of religious tourists, pilgrims who come to worship the Virgin Mary at her church, the Holy Church of Panaghia Evangelistria of Tinos – a custom which began, not by chance, during the days of the Greek Revolution – has always remained confined to the main town of Hora.

Nonetheless, for many years, this flow of pilgrims acted as a deterrent to other forms of tourism, consequently sparing the rest of the island from overdevelopment. That’s why I like to argue that Tinos was, in fact, literally saved by its Blessed Virgin!

To me, Tinos is its cultural landscape, its natural landscape and its people. It is its inland areas, it is Mr Tzortzis and his relationship with the land. It is its stone huts, small country churches, terraces and slowly crumbling dry-stone.

It is that “e-e-e-la” that resonates through the hillsides. It is its granite landscape around Volax and Falatados, the animal pens with their central monoliths, and the half-hidden detailing on the dovecotes. It’s also the dozens of handmade trails that trace ancient country roads through unexpected landscapes.

Tinos is the lesson in architecture offered by its 45 exceptionally well-preserved villages and the cool katogia (underground spaces) of its homes that continue to conceal treasures. It’s the moaning of the north wind as it slips through the covered alleyways of Tripotamos, Dio Horia and Steni.

Somewhere in the area around Kolymbithra Beach – but that’s as much as we’re willing to reveal!

© Maya Tsoclis

One of the hundreds of private chapels of Tinos, whitewashed and ready for its panigyri, a festival in honor of the saint to which it is dedicated.

© Maya Tsoclis

I confess that I find it difficult to believe that more than 30 years have elapsed since we, as a family, discovered the island. Another generation of people was around back then, one tied to the history and traditions of the place. It was as though things had remained unchanged for centuries, and this, undoubtedly, charmed us as well.

We used to enjoy wonderful Tiniot food in Ktikados at Taverna Drosia, which Vassili still runs and at which Ms Rini still cooks, and in Krokos, at Yia Mas, which was run by Ms Youstina and Mr Nikos. We enjoyed delectable fourtalies (omelets), homemade Tiniot cheese, louzes (cold cuts), artichokes in olive oil, gemista (rice-stuffed baked vegetables), imam bayildi (stuffed eggplants), pitsounia (squab) and rabbit with onions.

All produce was local, of course. And whenever you’d ask for the bill, Ms Youstina would always give you the same reply: “I don’t know… How much should I say, my dear?… Well, whatever you think is OK…” as though she were embarrassed to ask for money.

Time passed, and a feeling of uneasiness built as the older generation gradually vanished.

And then, a new renaissance emerged, essentially in the midst of the economic crisis.

Necessity spawned innovation. New ventures – such as the Cyclades Microbrewery, makers of Nissos beer, or the Tiniaki Ambelones winery (or T-Oinos) – created local products that went on to garner international awards.

The new generation of restaurateurs and producers broke new ground by creating the “Tinos Food Paths,” an inspired initiative that showcases Tiniot cuisine, putting collaboration and sustainability at the fore.

With new facilities producing cured meats and cheeses, new shops, new accommodation options for more upscale guests, and award-winning restaurants, tourism took off. This “misunderstood” island had now suddenly become “understood” and new admirers arrived, which frightened us somewhat.

Tarabados and, beyond that, Kambos, Xinara, Krokos and Koumaros. In the distance looms the mountain of Exomvourgo

© Maya Tsoclis

However, Tinos is a big island. You can be alone, if you wish. You can find deserted beaches in August, or take long solitary walks on marked trails through beautiful landscapes.

You can visit Exo Meri, where marble is king and where magnificent sculptors like Yannoulis Chalepas and Dimitris Philippotis were born, as was the painter Nikiforos Lytras. The Museum of Marble Crafts in Pyrgos, a member of the PIOP (Piraeus Bank Group Cultural Foundation) network of museums, is a great introduction to the world of marble and of marble working.

This is a craft which survives to this day: the sound of the mandrakas (a mallet-like tool) can be heard throughout Pyrgos, resounding from marble-sculpting workshops and from the School of Fine Arts. Faint echoes might even carry as far as the marble quarries and the villages of Marlas, Isternia and Kardiani.

Foreign publications like to present Tinos as the “authentic Cyclades” – and they aren’t wrong. The island has managed to preserve its appearance and its heritage – that is, its trinity of “nature, art and cuisine” – while retaining its soul as well.

However, they often forget to mention that the visitor who selects Tinos should approach the island with reverence: respect must be shown for people’s beliefs, for the prayers of Orthodox and Catholic Christians alike; for spiritual figures, like the nuns at Our Lady of the Angels; for the anguish and pain often suffered by pilgrims past and present; for the human toil that sculpted the landscape, working marble and other stone; for Aeolus, the wind god who chose Mt Tsiknias as his throne; and, finally, for the Tiniots themselves, who today are fighting to save their island – our island – from the “ambitious” investment plans threatening to convert this hand-hewn landscape into just another piece of real estate festooned with industrial wind turbines.

“This tomato develops from inside the earth. Do you see how it’s blossomed? Thirty years using the seeds from my own plants! The earth is the most pleasant thing there is. I’ve loved it, and, in return, the earth has offered me fruit, given me joy. Without joy, without love, there is no life…” After uttering these words, Mr Tzortzis strolls off to water his contented little zucchinis.

Igor Borisov turned Kimolos into his...

Patmos Aktis, Resort & Spa combines...

Discover Leros, a hidden Greek island...

New excavations shed light on an...