Skyros: Myth and Memory on the Island of...

A wild, storied island where the...

Achilles tending Patroclus wounded by an arrow, Attic red-figure kylix, c. 500 BC (Altes Museum, Berlin).

© Bibi Saint-Pol / Sosias Painter

All-conquering, semi-divine Achilles, the greatest of all the Greek warriors at Troy, is a hugely popular figure in Greek mythology, famed not only for his skills as a fighter but also for his magnificently complex character, often torn between fits of uncontrollable fits of rage, passion and grief.

Homer, the presumed author-composer of the Iliad and Odyssey, is the oldest and one of the best sources for Achilles’ exploits in the Trojan War, but many legends grew up around him in later Greek literature and other epic cycles, as well as in 5th century BC Athenian tragedy.

Born the son of Peleus, king of Phthia in Thessaly, and the sea nymph (nereid) Thetis, it was said that his mother dipped him in the waters of the River Styx to make him immortal. The only part of his body left vulnerable was his left heel, where she had held him (hence the expression “Achilles heel” for a weak spot, both physically and figuratively).

King Peleus sent his son to be educated by Chiron, the “wisest and justest of all the centaurs,” on Mount Pelion in southeastern Thessaly. Chrion instructed the young Achilles in the deadly arts of swordsmanship and archery, and cultivated him in music, poetry, medicine and botany.

As the Greek army assembled for the expedition to Troy, his mother divined that he will either gain everlasting fame and glory but die young, or live a long, uneventful life in obscurity. He chooses the former and leads a force of 50 ships to war, accompanied by his close companion Patroclus and his loyal warriors, the Myrmidons (literally “ant-people”).

At Troy, Achilles quickly distinguishes himself as the deadliest, most feared warrior among the Greeks.

Achilles fighting against Memnon, polychromatic pottery painting, c. 300 BC (Leiden Rijksmuseum voor Oudheden).

© Jona Lendering

Ajax carries off the body of Achilles, Attic black-figure lekythos, c. 510 BC (Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich).

© Bibi Saint-Pol

The central theme of the Iliad is the wrath of Achilles, sparked by Agamemnon, leader of the Greeks, stealing away his Trojan captive, Briseis. Enraged at the dishonor of being stripped of his prize, Achilles withdraws from the war and sulks in his tent.

Without their best fighter, the tide of the war quickly turns against the Greeks. On the verge of defeat, Patroclus dons Achilles’ armor and leads the Myrmidons into battle, momentarily driving the Trojans away, but is killed by Hector, the best of the Trojan warriors, in single combat.

Upon news of his friend’s death, distraught Achilles storms out of the Greek camp to rout the Trojans and kill Hector. In his blind fury, he even fights the river god Scamander, whose waters have become bloodied and choked by all the Trojan dead.

He eventually finds Hector and chases him around the walls of Troy three times before facing him in a duel. Hector accepts his fate but begs Achilles to respect his body and afford him the proper funerary rites, sacred to both Trojans and Greeks. Instead, Achilles kills him and drags Hector’s mangled body behind his chariot, returning to the Greek camp, his bloodlust sated.

It is only after Patroclus’ funeral that he returns Hector’s body to Priam, king of Troy and father of Hector for formal burial.

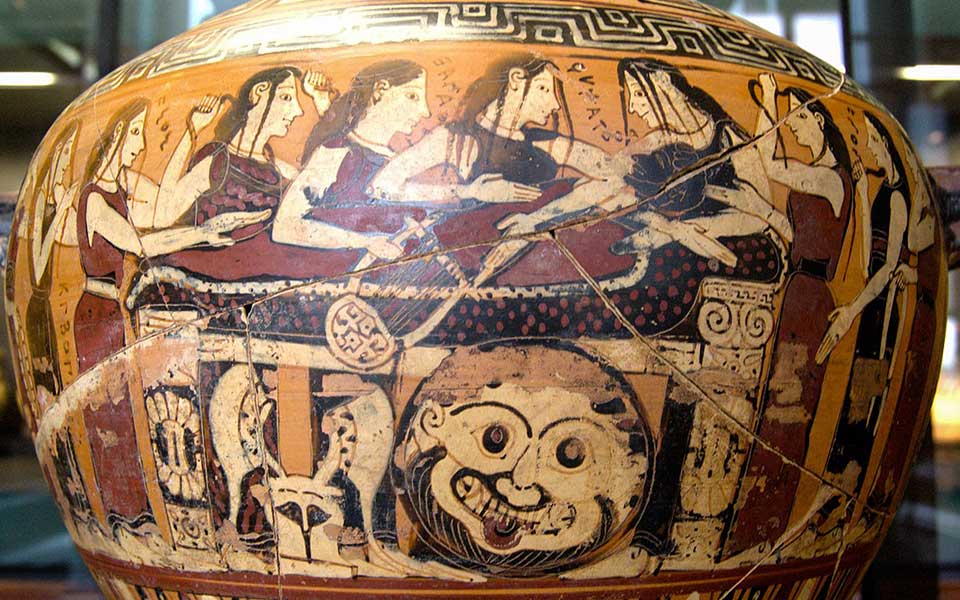

Thetis and the Nereids mourning Achilles, Corinthian black-figure hydria, c. 555 BC (Louvre, Paris).

© Bibi Saint-Pol / Damon Painter

There ends the storyline in Homer’s Iliad, but in later legends of the Trojan War, Achilles’ fate is revealed.

While scaling the gates of Troy, Achilles is killed by an arrow shot by Paris, brother of Hector, crouching hidden in a nearby tree. In some versions of the story, the flight of the arrow is guided by the Trojan-supporting god, Apollo, who held a grudge against Achilles for the brutal killing of prince Troilius in his own temple at the start of the war. The arrow pierces Achilles’ left heel, the only part of him that remains mortal, sending his shade to the Underworld.

Carried back to the Greek camp, his divinely-made armor, forged by the metalworking god Hephaestus, was later awarded to Odysseus, king of Ithaca, voted as the bravest among the Greeks and most deserving of the honor. Ajax, on the other hand, feels that he is most deserving, especially for having carried Achilles’ body off the battlefield. In Sophocles’ play Ajax, the hero storms off in a rage and commits suicide.

Throughout ancient Greek history, Achilles was a cult figure, worshipped and idolized in equal measure. Sanctuaries were erected in his honor throughout the Greek world, and he was venerated by the Thessalians. The kings of Epirus claimed to be descended from the hero through his son, Neoptolemus, one of the Greek warriors who famously hid inside the wooden horse at the end of the Trojan War.

Alexander the Great also claimed to be descended from Achilles and, in many ways, emulated his passion and valor, not only on the battlefield and as a great leader, but also in the love and loyalty he felt towards his men and his closest companion, Hephaestion. Like Achilles, Alexander was rash and compulsive, prone to uncontrollable rage and violence, but was clever and calculating and, perhaps, touched by the divine.

A wild, storied island where the...

From epic battles to avant-garde tragedy,...