Sacred Summits: Greece’s Ancient Mountain Sanctuaries

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...

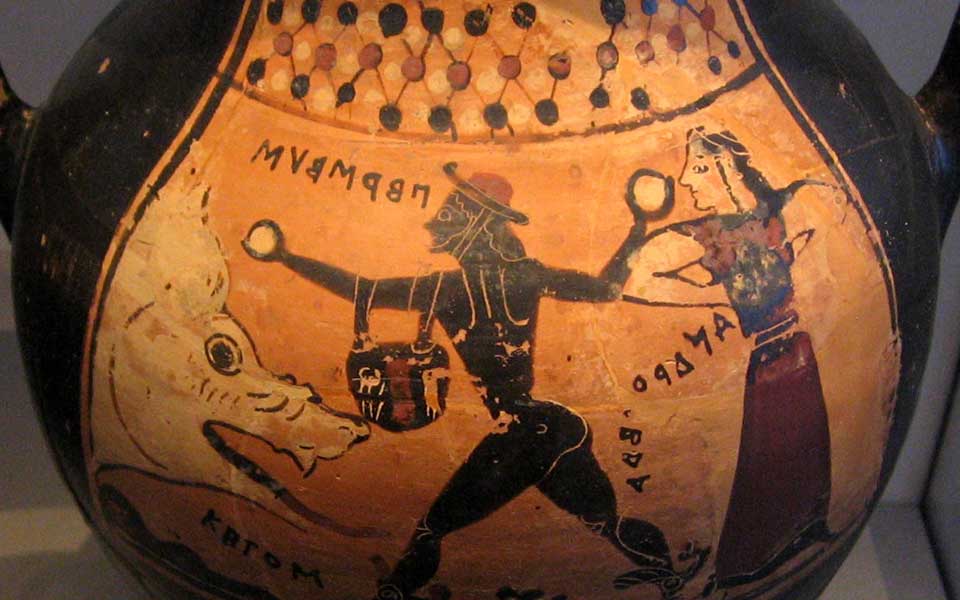

Ancient Boeotian bell-krater showing Zeus impregnating Danaë in the form of a shower of gold, c. 450-425 BC.

© Marie-Lan Nguyen

Aside from the all-powerful goddesses of Mount Olympus – Hera, Athena, Aphrodite et al. – Greek mythology often seems devoid of female characters.

In a bid to redress the balance, this entry in our “Who’s Who” series of lesser-known personalities in Greek myth recalls the story of Danaë, an Argive princess who, among other things, had a rather unusual encounter with Zeus – a god who, let’s be honest, did the craziest things to have sex!

Desperate for a male heir, Danaë’s father, Acrisius, king of Argos, consulted an oracle on how to procure a much-needed son to take over his hard-won throne. To his horror, the oracle replied:

“You will have NO sons, and your grandson must KILL YOU.”

In a desperate bid to forestall the prophecy, Acrisius imprisoned Danaë, his only child, in a dungeon with bronze doors, guarded by a pack of savage dogs.

Enamoured by her beauty, shape-shifting Zeus, king of the gods, turned himself into a ray of sunshine to evade the dogs, infiltrate the walls of the prison, and impregnated Danaë in a shower of gold – a bizarre way to procreate, even for Zeus.

The Roman poet Ovid captures the moment in his famous early 1st century AD epic poem, Metamorphoses (6.113):

“He [Zeus] courted lovely Danaë luring her as a gleaming shower of gold.”

Danaë receiving Jupiter [Zeus] in a Shower of Gold, by Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller (1787). It is said that Wertmüller toured with the painting, concealing it behind a curtain that, for a fee, he would draw aside as a kind of peepshow.

By Jan Gossaert (1527)

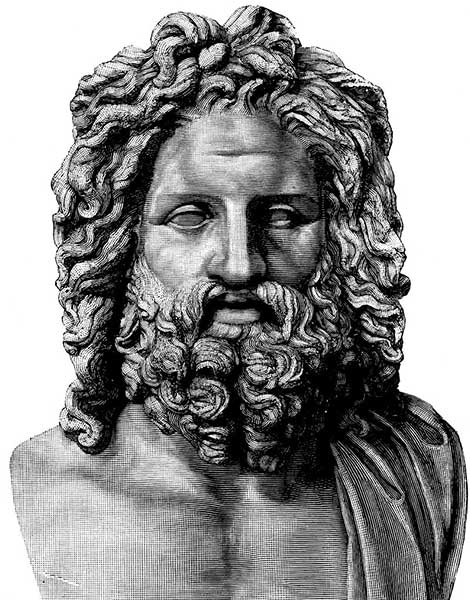

Illustration of the Otricoli head of Zeus. William Henry Goodyear, A History of Art: For Classes, Art-Students, and Tourists in Europe, A. S. Barnes & Company, New York, 1889. Page 158.

Nine months later, Danaë bore him a son called Perseus, who, in time, would go on to become one of the greatest heroes of them all.

With the ominous words of the oracle clamouring in his ears, enraged Acrisius, not wanting to incur the wrath of the Fates by murdering his own daughter (not to mention the offspring of Zeus), locked Danaë and her infant son in a wooden ark and cast them out to sea.

As if by a miracle – or perhaps the gentle guiding handing of a god (?) – the ark washed towards the island of Serifos in the southern Aegean and was netted by a fisherman named Dictys.

Hauled ashore, Dictys broke open the ark and found both mother and child still alive – seriously dehydrated and malnourished, of course, but alive. The kind-hearted fisherman took them to the local king, Polydectes, who raised Perseus in his own house.

As the years passed, Perseus grew up to be a headstrong and precocious young man, often defending his mother against the unwanted advances of Polydectes, seeking her hand in marriage.

In a bid to get rid of Perseus, the king, egged on by his loyal supporters, contrived a plot to send the young man away on a suicide mission (a common theme in Greek myth). Assembling his subjects in the palace, Polydectes announced that he was about to sue for the hand of Hippodameia, daughter of the wealthy king Pelops, for marriage, requesting they each contribute a horse apiece as a wedding gift.

Unable to provide a horse – but more than a little relieved to learn that the lecherous king was no longer pursuing his mother – Perseus rashly offered to fetch the Gorgon Medusa’s head as a gift instead, falling straight into the trap: “That would indeed please me more than any horse in the world,” replied Polydectes.

Now, the legendary tale of “Perseus and the Gorgon” is known well enough, and there is no need to recall it in any detail here. Nevertheless, it is important to note that Medusa was so appalling and terrifying in her appearance, with venomous snakes for hair, razor-sharp teeth and a revoltingly long and slimy forked tongue, that all who gazed upon her were so petrified with fright they turned to stone.

Perseus with the Head of Medusa by Benvenuto Cellini (1554). On display in Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, Italy.

© JoJan

Medusa, by Caravaggio (1595)

While Perseus was away on his mission, supported by the goddess Athena, who supplied him with a brightly-polished shield so as only to see the gorgon’s hideous reflection, and Hermes, who gave him a rather nifty pair of winged sandals and a special adamantine sickle to cut off her head, Danaë, continually pursued by Polydectes, sought refuge in a temple of Athena.

Upon his return to Serifos, Perseus, now accompanied by the beautiful Andromeda, whom he had rescued from the sea monster Cetus (NOT the Kraken – that’s an entirely different creature from the Norse sagas), went straight to the palace to confront the king. Greeted by astonishment, quickly followed by a barrage of insults, the hero produced the head of Medusa, thus turning Polydectes and his courtiers all into stone. (Incidentally, the circle of boulders on Serifos became a famous sight in antiquity).

Perseus then returned with his mother to Argos to claim the throne of his grandfather Acrisius and fulfil the prophecy. In various versions of the myth, Perseus accidentally killed his grandfather with a discus, carried out of its intended path by the will of the gods.

Perseus rescuing Andromeda from Cetus, depicted on an amphora in the Altes Museum, Berlin.

© Montrealais

The story of Danaë and the shower of gold was well-known throughout antiquity, inspiring poets, playwrights and artists. In Homer’s Iliad (14.319 ff), the early Greek poet describes Zeus’ feelings for the mortal princess in touching detail:

“Never before has love for any goddess or woman so melted about the heart inside me, broken it to submission, as now: not that time . . . when I loved Acrisius’ daughter sweet-stepping Danaë, who bore Perseus to me, preeminent among all men.”

One of several variants by Titian (1544). Cupid is alongside Danaë. National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples, Italy.

The erotic nature of Zeus’ visitation shocked early Christian leaders, most famously St. Augustine, but it soon became a favourite theme for Renaissance painters, many whom considered Danaë a symbol of the transfiguring effect of divine love. Some modern scholars view the myth as pastoral allegory, namely, water is “gold” for farmers and shepherds, and Zeus sends sunshine and rain on the earth – Danaë.

Danaë was the eponymous “queen” of the so-called Danaans, a term that was synonymous with Argive (people of the Argolid) but was sometimes used to describe Greeks in general (most notably in Homer).

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...