“Μost people live their lives without a purpose. Despina Achladiotou’s life has a purpose: to let passing ships know the islet of Ro is Greek. As soon as she spots a ship, she runs to the mast that has been set up on the beach, and raises and lowers the Greek flag several times. And the ship, according to the international courtesy rules of the sea, raises and lowers its own flag.”

These were the opening sentences of the April 1956 article in “Eikones” magazine, which made the “Lady with the Flag” famous across the nation. By then, Despina Achladiotou had already lived on Ro for 30 years – more than half of those alone. Over time, what this diminutive woman considered the most normal things in the world – not abandoning her island, raising the Greek flag – took on mythical dimensions, while she herself became a symbol of heroism and patriotism. Lucky are those who had the opportunity to meet her and experience her generous hospitality – she was so pleased to receive guests!

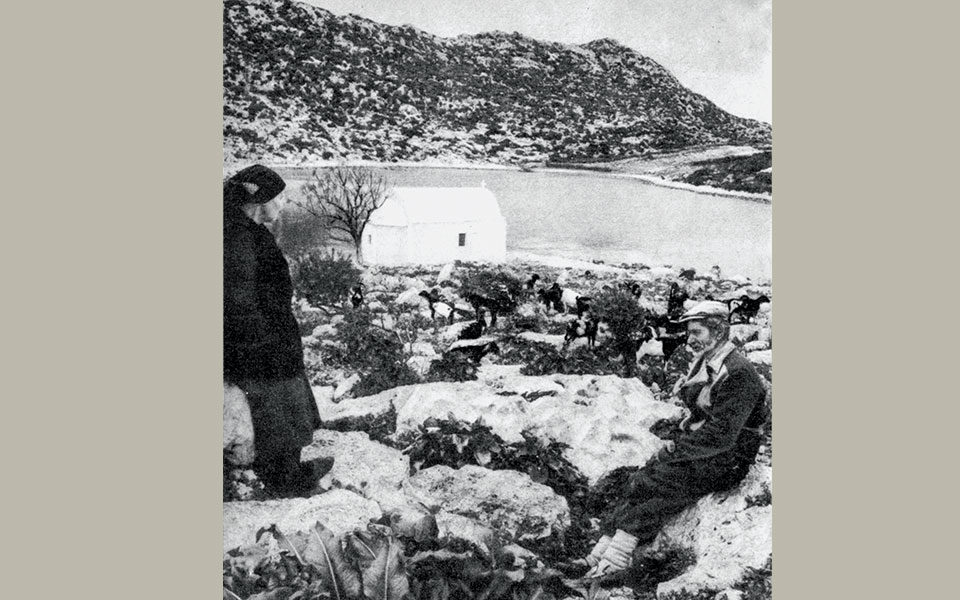

Despina Achladiotou was born in 1890. She settled on Ro with her husband, Kostas, in 1927, during Italian rule. At the time, the island was an uninhabited borderline between Turkey and the Dodecanese, and the municipality leased it to animal herders from Kastellorizo.

One day, about a year into their stay, a small team of Turkish soldiers disembarked from a motorboat and raised a Turkish flag on Ro. Despina reported the incident to the authorities on Kastellorizo. The Italian government took on the case, and asserted that the island was inhabited and therefore belonged to Italy, as did the other islands in the group. The Turkish flag fell unceremoniously.

© Municipality of Megisiti island archive

Despina and Kostas were the only inhabitants of the islet until 1940, when he fell ill. Nobody on Kastellorizo noticed the three fires that she’d lit as a distress signal, and so help came too late. Kostas died on the boat taking him to Kastellorizo.

After making arrangements for his burial, Despina returned to Ro with her mother. In the meantime, Greece and Italy had gone to war. Despina returned to Kastellorizo and began to help the Greek troops involved in the war effort in the Middle East, offering them food and lodging.

In 1943, after the surrender of Italy, the British ordered the evacuation of Kastellorizo and the surrounding areas, but Achladiotou refused to abandon her island, even after heavy German bombardment in November 1943. In her interview, she said, “They were firing and you could see the rocks falling. I said to myself, ‘This is the end of us.’”

After the bombings ceased, but with WWII still raging, sailors from the Greek Navy serving in the Middle East came ashore and discovered that Ro was inhabited by a woman and her elderly mother who welcomed them into their home and offered them food. On returning to their base, they informed their superiors, who sent a boatful of supplies. As that boat left, its crew saw the Greek flag flying over Ro.

When the islands were handed over to Greece, Achladiotou approached the military commander of Kastellorizo to ask: “Why not raise the Greek flag on Ro – so that everyone knows to whom it belongs?” The commander liked the idea. He ordered a flagpole be installed, and gave Achladiotou a brand new Greek flag.

From that moment on, raising the flag at dawn and lowering it at dusk became a daily task for Achladiotou. It was a task weighted with symbolism and one which gained perhaps even more importance after September 1975, when Turkish provocations (including the raising of a Turkish flag on Ro) against Greece began.

Achladiotou was decorated by the Greek Navy, and received honors from the Defense Ministry, the Athens Academy, the Municipality of Rhodes and other institutions. She died in 1982, aged 92 and was buried on Ro, next to the pole bearing the Greek flag, according to her last wishes.

© Photo from Eikones magazine, Vasos Migkos

“Now, she wants her peace…”

In her 1981 book, “Kastellorizo,” author Marie Karioti recounts a particularly pleasant visit to the Lady of Ro.

“I was told I would find her at the house with the flag. And so it was. Four flags flew on the island every day, from east to west. A large one on the tower, one on the coastguard building, one on the hotel and one on the house belonging to the Lady of Ro.

“I went up the steps and found her seated on the wooden sill of her open window. On the wall of her pristine house was an icon niche with many photographs. Photographs of Athenian celebrities, which she showed off with pride, and photographs of her relatives, living far away over the seas.

“As I listened to her and watched her, I felt a pride approaching envy for this authentic woman of our land.

“Many years had passed since she married a shepherd and gone to live with him on the island of Ro. They did not have children. Looking at her, I could feel the disappointment that this must have caused her and her husband. I imagined her anguishing over the thought of a child for hours, days, years, in the loneliness of the house, or while herding her goats and cattle.

“Her husband was good to her; I heard nothing more of his personality. For the winter evenings, the Lady of Ro had five books: a copy of Erotokritos; a hagiography; a biography of the Greek revolutionary hero Tzavellas and two other books whose titles I don’t recall, which she read by the light of a lantern.

© Photo from Eikones magazine, Vasos Migkos

“One day, a cow developed a boil on its head. Her husband heated an iron to cauterize it, but the cow reared up and kicked him in the chest. He took to bed and got worse by the day. It was winter, and the sea was rough. A signal was sent… a boat was dispatched, and together they set off for Kastellorizo. On the crossing, he passed away. When the boat reached Kastellorizo harbor, the mourning began.

“Achladiotou stayed on at Kastellorizo for some time, but her livelihood was on the island of Ro. So she returned with a relative. But her heart was still tortured by pain and loneliness and, as if wanting to destroy every last vestige of her former happiness, she threw her five books into the fire, and spent winter alone in front of the fireplace gazing at the flames.

“Every morning she raised the Greek flag, and lowered it at dusk. The captains passing by the island blew the horn in salute, either for the Lady or Ro or for the flag. With the passage of time, this sounding of the ship horns became a tradition.

“And so the years went by. The Lady of Ro eventually went to live in her old house on Kastellorizo. There she raised the flag each morning on her small balcony. One day, suddenly, she became famous and all of Greece talked about her. She got tired though, and now, as she told me, she wants her peace…”