Located on the outskirts of the ancient city of Amphipolis in central Macedonia, the Kasta Tomb – otherwise known as the Amphipolis Tomb – is the largest and most lavishly decorated funerary monument ever discovered in Greece. Dated to the last quarter of the 4th century BC, scholars associate the site with the famous Argead dynasty of Alexander the Great, one of history’s most successful military commanders, and the bloody events that were triggered by his untimely death at the age of 32, in June 323 BC.

Characterized by its enormous size and intricate design, the discovery of the tomb has sparked intense debate about who was buried there. Its proximity to the site of ancient Amphipolis, an important strategic and economic center of the Macedonian-Greek empire, strongly suggests it was built for a person of great importance, directly connected to the ruling family.

When Alexander died unexpectedly in Babylon at the height of his power, he left no obvious successor. His wife Roxana was pregnant at the time with his son, the future Alexander IV, but the absence of a designated regent to rule in his stead led to a bitter power struggle among Alexander’s battle-hardened generals, known as the “Diadochi” (Successors), to assert control over his vast empire. The ensuing conflict, known as the Wars of the Diadochi, lasted for decades, with shifting alliances, betrayals, and military campaigns that stretched the length and breadth of Alexander’s empire, from Greece to the Indus Valley. The result was the fragmentation of his empire into four main Hellenistic kingdoms – the Seleucids, Ptolemies, Antigonids, and Antipatrids – and several smaller regional states.

Following the discovery of human remains in the Amphipolis Tomb in 2014, public speculation regarding their identity went into overdrive. Was it the intended burial place of Alexander the Great? But if the ancient sources point to Alexandria in Egypt as his final resting place, was it constructed for someone closely associated with him? If so, who?

© Public domain

Human remains

The earliest archaeological excavations at the Kasta tumulus (burial mound) in the mid-1960s revealed a vast circular wall, 3m high and 158m in diameter, made of limestone and covered with marble that was imported from the North Aegean island of Thassos, over 60km away.

The tumulus itself is nearly 500m in circumference and towers 30m from ground level, forming an imposing feature in the landscape that is visible from miles around in every direction; an astonishing feat of engineering. The foundations of a 10m-square building on top of the mound, discovered in 1973, are thought to have formed the base of an elaborate grave marker, perhaps a colossal lion sculpture, a symbol closely associated with the ruling Macedonian dynasty.

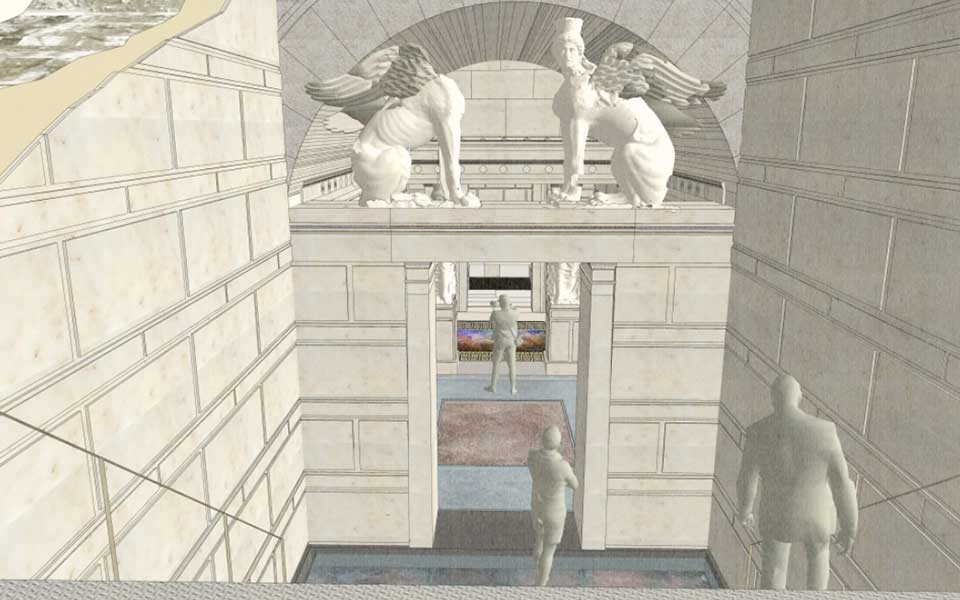

As excavations resumed in 2012, the tumulus was once again thrust into the public eye when the Greek Ministry of Culture announced the discovery of an inner tomb at the bottom of a 13-step staircase, guarded by a pair of 2m-tall marble sphinxes perched atop the entrance, their missing heads and wings an ominous sign that the tomb had already been raided.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Upon entering the tomb, the archaeologists revealed three separate chambers, covering an area of approximately 500 square meters, and adorned with exquisite sculptures, wall frescoes, and a richly detailed floor mosaic, depicting the abduction of Persephone into the Underworld by Hades. But the best was yet to come …

In early 2015, the Ministry announced the discovery of the remains of five individuals in the third chamber, the main burial chamber, sparking excitement in the media and intense scholarly debate among archaeologists and historians.

The barrel-vaulted tomb, looted in antiquity, contained the skeletal remains of a woman over 60 years of age, found at the bottom of the box-shaped “cist” grave in the floor, as well as the scattered bones of two men, aged approximately 35 and 45 respectively, a newborn infant, and the fragments of a cremated adult of indeterminate age and sex. Only the elderly woman’s skeleton had a skull. Close investigation of the younger man’s bones revealed unhealed wounds, deep cut marks, suggesting he had met a violent death.

Four possible candidates

Despite extensive forensic analysis, the exact identity of the tomb’s five occupants remains a mystery. Key researchers have developed several theories concerning the intended occupant of the cist burial, and while the excavation team believe the tomb was originally built for Hephaestion, Alexander the Great’s “Chiliarch” (chief military commander) and closest friend, who predeceased him in 324 BC, others argue it is the final resting place of an extremely powerful and influential woman in Alexander’s life.

Let’s take a closer look at the four candidates currently being debated by the experts:

Hephaestion (c. 356 BC–October 324 BC)

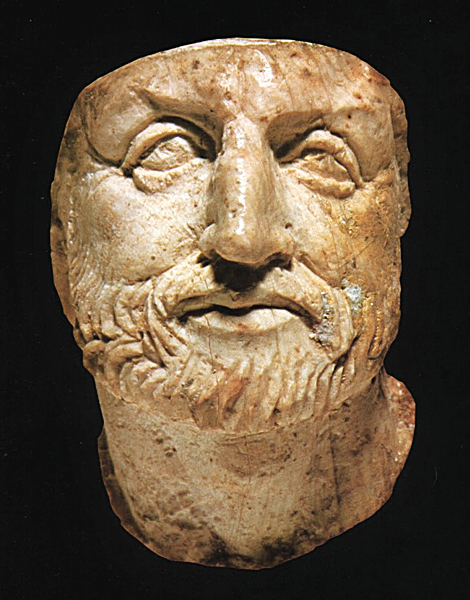

Hephaestion was Alexander’s closest and most trusted companion, playing a significant role in his life and military campaigns. Born into an aristocratic family in Pella, Macedonia, around 356 BC, he shared Alexander’s education under the tutelage of the philosopher Aristotle, forging a deep bond with the young Macedonian prince. Ancient biographers, including Curtius, describe Hephaestion as “the dearest of all the king’s friends; and shared all his secrets,” adding that he possessed qualities that complimented Alexander’s own personality, such as loyalty, intelligence, and courage. Historians have compared their relationship to the Homeric figures of Achilles and Patroclus.

During Alexander’s conquests of Asia, Hephaestion held important positions in the army and its administration, playing a crucial role as a member of the king’s personal bodyguard (“Hetairoi”) and a commander of the elite Companion Cavalry.

Tragically, his life was cut short when he fell ill of typhoid fever (?) and died suddenly in 324 BC in Ecbatana, Persia. Alexander was distraught by his friend’s death and mourned him deeply, organizing a lavish and costly funeral in Babylon and ordering the construction of heroic shrines and monuments throughout the empire. The Greek biographer Plutarch, writing in the first/second century AD, described Alexander’s grief as “uncontrollable.”

The case for Hephaestion as the main occupant of the Amphipolis Tomb has been put forward by the chief archaeologist of the current excavations, Katerina Peristeri. It is based on two graffiti inscriptions of the word “[π]αρέλαβον” (meaning “received”) on two stone blocks that have detached from the retaining wall around the Kasta mound, and a monogram of the letters ΗΦ (“Hephaestion”?) on a roof slab inside the tomb.

While this theory has gained traction in academic circles, some scholars have dismissed the epigraphical evidence as unconvincing, saying that the tomb was built around a pre-existing cist grave intended for inhumation (i.e., the non-cremated remains of the dead). We know from the historical sources that Alexander planned an elaborate cremation for Hephaestion atop an enormous funeral pyre, 60m high, decorated with golden-prowed ships and delicately carved sculptures – a permanent memorial. Whether the funeral pyre was lit and Hephaestion’s cremated remains were entombed within is open for debate. Historian Robin Lane Fox argues that the pyre was likely never completed, as Alexander himself died less than eight months later.

The fragmented remains of the younger man in the Amphipolis Tomb roughly correspond in age to Hephaestion, who was about 32 when he died, but the bones reveal deep wounds that would have almost certainly been fatal. And while it’s likely that Hephaestion sustained injuries and battle scars during the many years of campaigning, all the ancient sources agree that he died of a fever over a thousand kilometers away in Persia, and his body was never returned to Macedonia.

Olympias (c. 375–316 BC)

Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was a remarkable and hugely influential figure in ancient Macedonian-Greek history. Born around 375 BC, she belonged to the noble Epirote Molossian dynasty (ancient Epirus) and married king Philip II of Macedon, cementing a strategic alliance between the two kingdoms.

Olympias was known for her strong personality, intelligence, and deep devotion to the religious and mystical beliefs of her ancestral lineage, which claimed descent from Neoptolemus, son of Achilles. She was deeply connected to the ancient Greek religious cult of Dionysus, often associated with ecstatic rituals and fervent worship. Her connection to mysticism and alleged involvement in cultic practices added to her enigmatic and sometimes intimidating image. Indeed, her beliefs and influence likely contributed to Alexander’s own sense of destiny and ambition.

During Philip II’s reign, she faced political intrigue and rivalries within the Macedonian court and was often seen as a threat. After Philip’s assassination in 336 BC, Olympias’ influence increased as she supported and protected her son’s ascension to the throne. However, her relationship with Alexander became strained over time, especially during his long and protracted military campaigns in the East, and was accused of meddling in the affairs of state.

After Alexander’s death in 323 BC, Olympias faced political turmoil and was eventually murdered on the orders of Cassander, one of Alexander’s generals, in 316 BC, aged 59.

The case for Olympias as the primary occupant of the Amphipolis Tomb is popular among scholars, largely due to the remains of a woman who died at approximately the same age as Olympias being the likely occupant of the cist grave in the main burial chamber. The iconography of the decoration in the tomb also strongly suggests a high-status female occupant, sphinxes being symbols of the queen of Macedon, as well as a pair of caryatids (maidens) at the entrance of the second chamber. However, some have pointed out that Cassander, as the unconditional ruler of Macedonia following Alexander’s death, would not have built such a lavish tomb for his archenemy. After all, Olympias had been responsible for the death of his brother, Nicanor, and was implicated in the murder of many of his friends and supporters.

Writing at the end of the 1st century BC, the historian Diodorus Siculus records that Cassander had besieged Olympias in the Macedonian city of Pydna, where she was eventually killed by the relatives of her victims, “wishing to curry favor with Cassander as well as to avenge their dead.” And while Diodorus states that Cassander “left her unburied,” the skeletal remains of the elderly woman in the tomb being of similar age to Olympias at the time of her death is an intriguing coincidence. Also, could the scattered bones of the two men in the tomb belong to two loyal retainers who were both cut down while trying to defend the queen?

Scholars have called for a DNA study to be carried out on the woman’s remains by extracting a trace sample from her tooth enamel, which would help to confirm her ancestry and genetic traits. If the strontium levels in the enamel match those from the Molossia region of Epirus, where she was born and raised, the remains may well be those of Alexander the Great’s mother.

© EPA, Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Roxana (c. 340 BC–310 BC)

Alexander’s wife, Roxana, was born around 340 BC in the region of Bactria, Central Asia (modern day northern Afghanistan, southwestern Tajikistan, and southeastern Uzbekistan). In her early teens, she married Alexander in 327 BC to strengthen political alliances and foster goodwill between the Macedonians and the people of Bactria. But her role as Alexander’s wife was not solely ceremonial. As queen consort, Roxana actively participated in his military campaigns, and her presence boosted the morale of the Macedonian troops as they continued to fight in the East.

Roxana became pregnant with Alexander’s child shortly before his death in 323 BC, after which she gave birth to a son, named Alexander IV. In the political turmoil that ensued, Roxana and her infant son became political pawns, as rival factions sought to gain power and influence. They both came under the protection of Alexander’s mother Olympias, but, following her assassination in 316 BC, were imprisoned by Cassander in the citadel of Amphipolis as he sought to eliminate potential rivals.

In 311 BC, the 11/12-year-old Alexander IV was briefly confirmed king of Macedon, with Cassander acting as his guardian, but he and Roxana were soon murdered, sometime in 310 BC, marking the end of the direct line of Alexander the Great and the Argead dynasty. The exact circumstances surrounding their deaths remain unclear, but it is believed that their elimination was motivated by Cassander’s desire to consolidate power for himself.

There is little to link Roxana and the young Alexander IV to the Amphipolis Tomb except that they were both in the city when they were killed. The remains of the newborn infant in the tomb are far too young to be Alexander IV, and Roxana herself would have been around 30 when she died, too young to be the elderly woman in the cist grave. Nevertheless, could the fragmentary remains of the cremated adult be Roxana?

© Public domain

Cynane (c. 357-323 BC)

A fourth and somewhat intriguing possibility is Cynane, the daughter of Philip II of Macedon and Audata, an Illyrian princess. Born sometime around 357 BC, she was the older half-sister of Alexander the Great.

Raised by her mother, Cynane was trained in “the arts of war” and, according to the historian Polyaenus, personally slew an Illyrian queen in battle. Philip II married her to his nephew Amyntas, with whom she bore a daughter named Adea (c. 337-317 BC). Her husband Amyntas soon died following Alexander’s accession to the throne in 336 BC, and she did not seek another marriage.

Cynane’s ambition and desire for power became evident when she attempted to secure the Macedonian throne for her daughter. She proposed a marriage alliance between Adea and her half-brother’s son, Alexander IV, but her plans were met with fierce resistance from the Macedonian nobles. Ultimately, Cynane’s political aspirations were thwarted, and she was assassinated, in 323 BC, shortly after her half-brother Alexander’s death.

Although her life was cut short, Cynane’s legacy as a fierce and capable military leader and her attempts to secure power for her family mark her as a notable figure in ancient Macedonian-Greek history. Her story reflects the complex dynamics of power, ambition, and gender roles in the ancient world.

Historian Peter Delev makes a powerful case for Cynane as one of the intended occupants of the Amphipolis Tomb, claiming that, as a high-standing member of the royal family and a daughter of Philip II, she was “greatly revered by the Macedonians,” and would have been afforded due respect and an appropriate funerary monument.

Her daughter, Adea, went on to marry Philip III of Macedon, changing her name to Eurydice. As queen, she would have had the power and the means to commission the construction of the Amphipolis Tomb. As such, she may have arranged for the internment of the cremated remains of her mother, Cynane, along with her grandmother, Audata, who was around 60 years old when she died, matching the skeletal remains of the elderly woman in the cist grave.

Another interesting twist is the fact that the fragmentary remains of the younger man in the tomb may belong to Cynane’s husband, Amyntas, who was killed and buried after the accession of Alexander, and would have been around 30 years of age at the time of his death.

A tomb fit for a queen?

Not only does the sheer size and grandeur of the Amphipolis Tomb stand as a lasting testament to the advanced architectural and artistic achievements of the ancient Macedonian-Greeks, it offers a tantalizing glimpse into the political intrigues of the time.

It is highly likely that the decoration of a 4th century BC Macedonian tomb, in this case depicting strong female iconography – the sphinxes, the Caryatids, and the mosaic of Persephone with flame-like red-gold hair – would be directly associated with its occupant. Intriguingly, Persephone’s reddish-blond hair color in the mosaic was famously associated with the Epirote Molossian dynasty of Olympias; its mythical founder, Neoptolemus (“New Warrior”), being named “Phyrrhus” (meaning flame-red in Greek) at birth. Indeed, the Roman historian Claudius Aelianus, writing in the early 3rd century AD, recorded Alexander’s own hair color as follows: “They say that Alexander, the son of Philip, was naturally handsome: his hair was swept upwards and was golden-red in colour.” (Aelian, Varia Historia 12.14). Could the iconography point to Olympias as the intended occupant of the cist grave?

As ongoing research and excavation continue, the tomb promises to unravel more secrets and deepen our understanding of this fascinating period in ancient history.

After reviewing some of the main contenders, who do you think was buried in the Amphipolis Tomb?