What were spring festivals like in ancient Athens? Maria Lagogianni, director emerita of the National Archaeological Museum (NAM), speaks to the Athens-Macedonia News Agency and describes the spring public festivals in classical Athens – of course, this doesn’t mean that there weren’t other festivals taking place all year around.

“Spread out throughout the course of the year, the Attic festive calendar filled a large part of people’s everyday routine, offering relaxation and pleasure, with therapeutic and liberating effects, while also cultivating a sense of historical memory and social cohesion,” notes Ms. Lagogianni.

She adds: “Independently of the private, devotional practices at home, Attic festivals generally had a public aspect and a political slant. The citizens of Athens actively participated in the city’s celebrations and perceived time in relation to these events, as the Attic calendar was divided into twelve lunar months. The year began with the first new moon after the summer solstice (July 21-22), with the month called Hekatombaion (July-August). This coincided with the political year, which began with the new eponymous archon taking power, who would give his name to his year of office.”

So what were the festivals that embellished the lives of ancient Athenians in the spring? How many were mystical, with holy vigils or grandiose processions? To which gods did they dedicate their hymns, devotional or ecstatic dances? What type of sacrifices, libations or chthonian dedications accompanied them? Maria Lagogianni, former director of the NAM and the Epigraphical Museum of Athens, shares her knowledge with us.

© Shutterstock

Celebrating the advent of spring

The first springtime festival in ancient Athens was the Anthesteria, which also marked the coming of spring. The festival honored the god Dionysus and lasted three days, from the 11th – 13th day of the month of Anthesterion, which falls somewhere between the end of February and the beginning of March.

“During the first day of the Anthesteria, the Pithogia, Athenians cracked open their large jars of new wine and offered libations to the sanctuary of Dionysus at Limneon (possibly next to the Temple of Olympian Zeus). They would then make merry with the slaves in cheerful feasts, tasting the new wine in honor of the god of wine and revelry. The same day, they would give children wreaths made of flowers and various toys, while also allowing them to taste wine for the first time, drinking from smaller ceramic jugs. A series of these minute wine jars decorated with cute scenes of carefree children are on display in the permanent collection of the National Archaeological Museum (Room 56),” Maria Lagogianni shares with us, urging us to visit the Museum again as soon as possible.

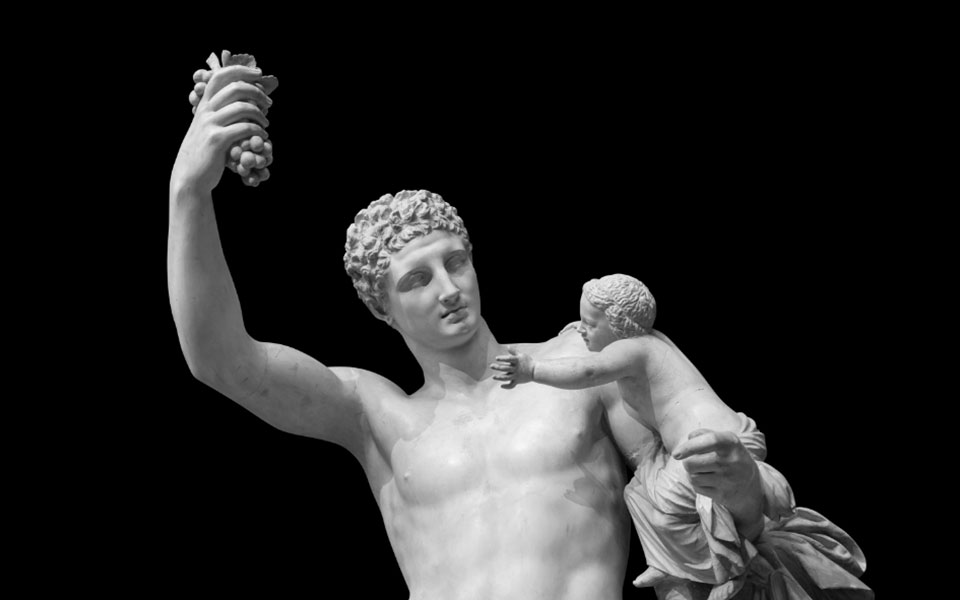

But the celebrations in the city did not stop after the first day. “The second day of the Anthesteria, the Choes, would include a drinking contest which involved celebrants drinking the ‘pain relieving’ gift of Dionysus from wine jugs called choes. It was commonly accepted that ‘if it were not for wine, all love and joy would have to disappear from the human world,’ as Euripides laments in his play, ‘The Bacchae’ (lines 772-774). But the most important ritual of the day was mystical in character, filled with the symbolism of fertility. It was about the sacred ritual marriage of Dionysus to the so-called Vasilinna, wife of the chief magistrate, the official responsible for the city’s religious ceremonies. This paradoxical ritual had ancient roots and in a way, symbolized Dionysus’ conquest of Attica. This day was also when the ghosts of the dead were believed to leave Hades and walk around the city. To avoid these ignoble spirits on the loose, Athenians would smear their doorways with pitch, hang disgusting wreaths of flowering buckthorn, and cordon off the temples (except that of Dioynsus),” she describes.

On the third day of the Anthesteria, the Chytroi, the city was in mourning. As Maria Lagogianni tells us, “the day was dedicated to Hermes Psychopompos (Hermes the Conveyor of Souls) and to the souls of the dead. Every house would prepare various grains in clay pots as offerings. On the same day, the young men and women of Athens would get on hammocks (swings), following a funerary tradition of atonement for the death of Erigone, daughter of Icarius. According to the myth, Icarius was taught by the god Dionysus himself to make wine. Being inebriated for the first time, Athenians thought they had been poisoned, so decided to punish Icarius and killed him. Erigone could not take the pain, and hanged herself from a tree.”

© Shutterstock

The Rural Diasia

Ten days after the Anthesteria, on the 23rd day of Anthesterion (early March), in the beautiful area of Ilissos, outside the city walls, was held a great public spring festival – the Diasia.

“The day was dedicated to Zeus Meilichios, whose symbol was the domestic serpent, the snake that protected the home. Ancient writers claim that people would give local offerings, cakes with honey in animal forms, to honor the god. For celebrants, the program also included food and spectacle: hearty feasts, hymns and horse races,” the director emerita of NAM notes.

Pastries, evening processions and drama contests

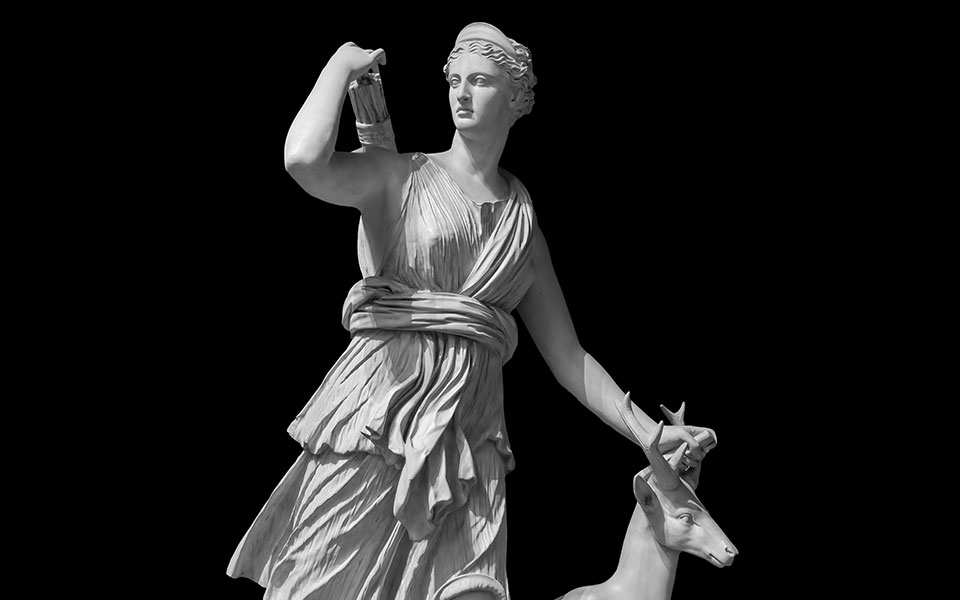

The ninth month of the Attic calendar was called Elaphebolion and partially coincided with our months of March and April. As she notes, “its name comes from the Elaphebolos, a celebration dedicated to the goddess Artemis Elaphebolos (deer slayer). In her honor, Athenians would sacrifice deer. Later, this ancient ritual was replaced with non-sacrificial offerings of delicious pastries made with wheat flour, honey and sesame seeds, in the shape of stags.”

During days 8-13 of the Elaphebolion (end March), the City Dionysia would be celebrated, a large festival in honor of Dionysus.

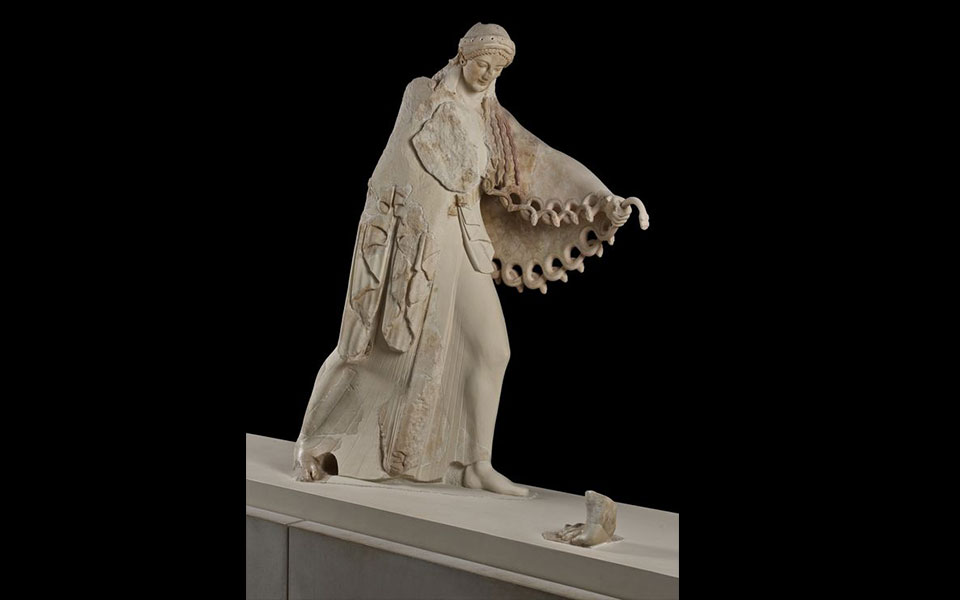

“In their evolved form, the City Dionysia was a wonderful festival combined with the devotional rituals of the older Rural Dionysia, with theater and drama contests. One day before the festival, Athenians would take the wooden statue of the god to a small temple in the Academy. The next day involved the proagon, when the playwrights and actors were presented to the audience. In the evening, a grandiose procession of torch-holding celebrants would return the wooden statue of Dionysus to his sanctuary on the southern incline of the Acropolis, where the theater of Dionysus is located.

“On the morning of day 9, a large celebratory procession would carry an effigy of a phallus to the sanctuary of Dionysus. A circular ritual dance by boys and men singing the dithyramb would follow. The day would finish with the komos, a merry procession of celebrants along the model of the Rural Dionysia. The following days were dedicated to drama contests: the 10th to comedy and the last three to tragedy. The transformation of the simple Dionysia into the evolved form of this drama contest is one of the largest achievements of Athenian democracy,” she tells the Athens-Macedonia News Agency.

© theacropolismuseum.gr

The “April-May” celebrations: promoting the grandeur of the city

The 10th month of the Attic calendar, called Munichion, partially fell in our months of April and May. It is named after the Munichia, a celebration in honor of the goddess Artemis, who was worshiped in her sanctuary in the Munichia peninsula, in Piraeus. “On the 16th day of the month, Athenians would honor the goddess by organizing a procession towards her sanctuary. A sacrifice and offerings of pastries called amfifontes, especially prepared for the occasion and decorated with burning candles, would follow. The spring celebration also included the nautical games of ephebes (young men) that took place in memory of the naval Battle of Salamis, and to honor the goddess Artemis, who had contributed to the Greek victory by taking the form of the full moon,” notes Lagogianni, explaining that the anniversary of the battle had been moved to this day from the end of September.

The festival of the god Eros would take place on the 4th of this month, while on the 6th, Athenians would honor Apollo Delphinios. “According to the myth, Theseus – before sailing for Crete – dedicated an olive branch wrapped in white wool, also known as iketiria, to Apollo Delphinios. In memory of this event, Athenians organized a procession made up of young girls, who symbolically would hold iketiria as they made their way to the temple of Apollo Delphinios (south of the Temple of Olympian Zeus). On the 19th day of the same month, they celebrated the Olympeia, a grand festival that included a procession with horses. They say this festival was established by the tyrant Pisistratus, in memory of laying the foundations for the grandiose Temple of Olympian Zeus,” she says.

© Shutterstock

Τhe end of spring: ritual cleansing and a festival for foreigners

The end of spring and the beginning of the summer was marked by Thargelion, the 11th month of the Attic calendar that fell between mid-May and mid-June.

“This month included many celebrations, starting from the Thargelia in honor of Apollo and Artemis. On the first day of the festival (6th day of Thargelion), the citizens of Athens would carry two convicts around the city, the pharmakos or katharma, who as scapegoats were meant to absorb every miasma. At the end of this cathartic ritual, they would throw the pharmakoi into the sea or exile them from the city to rid themselves of any abomination or bad luck. The second day of the festival (7th day of Thargelion) was more cheerful, as it included a procession, musical contest and consumption of the first fruits of the season, boiled or kneaded in bread,” explains Lagogianni.

There was also the Bendidia festival, celebrated in the same month at the port of Piraeus, by locals and by foreigners. “It was in honor of Bendida, the Thracian goddess whose worship dates from the end of the 5th century BC. According to ancient writers, a double procession was held on the day – one composed of native Greeks and one of Thracians, while at night there was a horse procession with lit torches,” Lagogianni says as she comes to the last festival of Thargelion, the Plynteria. “This was about the ritual cleansing of the ancient wooden statue of Athena Polias, which was taken via a procession to Faliro and washed in the sea, together with her dress (peplos), by two young girls called the loutrides or plyntirides. It was then returned to the Acropolis in another procession, accompanied by lit torches. This was the only event of the day, as people approached it as somewhat of a national holiday. In fact, the Athenians considered it among the apophrades (impure days on which temples were closed and business was not done) and very unlucky. They would cordon off the city’s temples with rope to protect them from evil spirits and not engage in any religious services, while they would also close the courthouses. Overall, completing any serious affair on this day was avoided out of superstition.”

Source: Athens-Macedonia News Agency