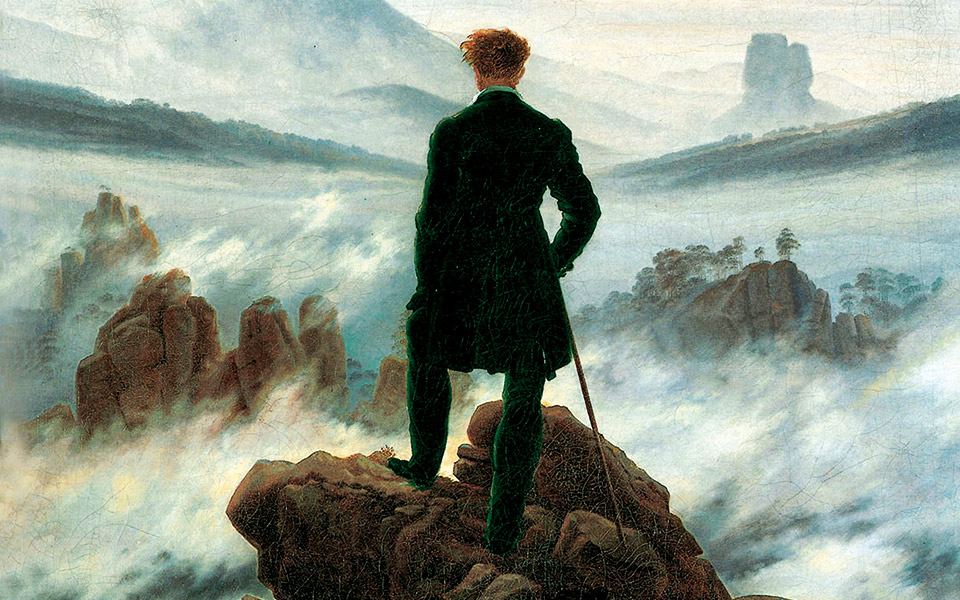

A man looks at the landscape that stretches out in front of him. Is it Caspar David Friedrich’s protagonist facing the foggy abyss? Or perhaps Odysseus, confronting the lightning-struck sea that separates Calypso’s island from his bed at home in Ithaca?

Odysseus, as we all know, is tormented by “nostos,” a term in ancient Greek literature – he desperately wants to go back home:

“Him she found sitting on the shore, And his eyes were never dry of tears, And his sweet life was ebbing away, as he longed mournfully for his return, For the nymph was no longer pleasing in his sight.” (Passage from Homer’s “Odyssey”, 151-5, translation by A.T Murray, 1919)

Yet what does the romantic 19th-century figure long for at the edge of the precipice? What is he thinking of? Could he be the ancestor of the stereotypical German tourist, the one that, inevitably, we all have run into, crossing the Samaria gorge with an almost irritating enthusiasm, or roasting under the sun on the most inaccessible Cycladic beach – fully nude, naturally – or even smiling at us from a table at Barba Yiannis’ kafeneio, wearing socks with his Birkenstocks?

The German word that describes the longing of return is “Heimweh” – homesickness – which sources say was introduced by Louis XIV’s hardhearted Swiss mercenaries. The war’s hardships might not have affected them, but memories of their homeland’s immaculate mountain tops and crystalline lakes plunged them deep into despair. (Paradoxically, the term “nostalgia” with its Greek roots actually owes its origin to Swiss doctor Johannes Hofer, who coined it in 1688).

“Heimweh,” embedded in the German vocabulary, was in need of an opposite: “Fernweh” is the irresistible urge to cut oneself from what is familiar, the longing to visit faraway and unknown lands, the thirst for something different. Could this thirst be the motive of the man in the mountains? Is he desperately longing to face the unknown? Does he simply want to escape the dull horizons of his “pale motherland,” or to return to the ruins of a mythical past which felt more carefree and more luminous?

And what about us? What torments us the most in these strange times of confinement? Is it our longing to go outside and conquer mountain tops that have never been walked on? A childish rebellion against prohibition? This peculiar feeling that currently overwhelms us corresponds to yet another German word: “Unheimlich”, the uncanny – literally meaning “unhomely.”

Once more, we encounter the term “heim” (home, residence, familiarity), this time next to the negative prefix “Un”. We tend to think that we are scared by the unknown, the uncanny; nevertheless, as Freud assures us, “the uncanny is that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.” French philosopher Barbara Cassin, in her work “Nostalgia: When Are We Ever at Home?” puts it slightly differently “Nostalgia is what makes one prefer going home, even if it means finding there a time that passes by, death — and worse, old age — rather than immortality.”

In the same way, Odysseus chose his ageing wife and his mere human destiny over an immortal goddess and eternal life. We, too, these days gaze over whatever landscape stretches out in front of us, caught between the desire for the safety of home and the desire to drift away. We are conflicted because, deep down, the adventurer Odysseus is a homebody, and Caspar David Friedrich’s narrator, who has reached the edge of the horizon, might in fact want to leap into the void.

This is precisely what Fernweh is, according to author and photographer Teju Cole: “The cure and the disease are one and the same. Fernweh is the silver lining of melancholia around the cloud of happiness about being far from home. The term “at home” describes both a location and a state of being. You can stay at home or feel at home, and often those two notions coincide.”

Perhaps all we need is to feel “at home” wherever we are right now, and wherever we may find ourselves in the future – all of us who, now more than ever, are longing for open horizons and the liberty to drift away.

This article was first published in Greek at kathimerini.gr