The Secret Life of the Odeon of Herodes...

A monument of memory and music,...

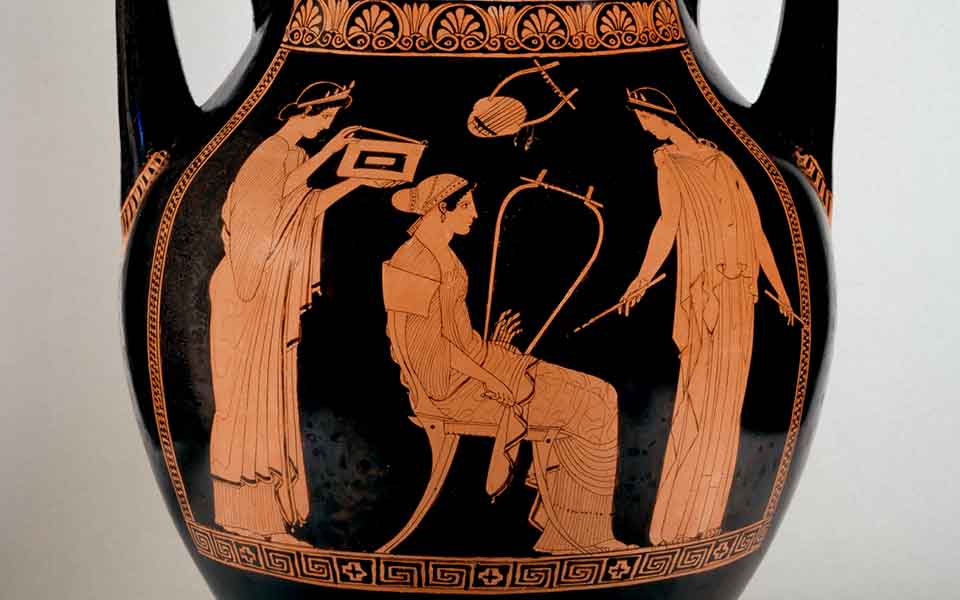

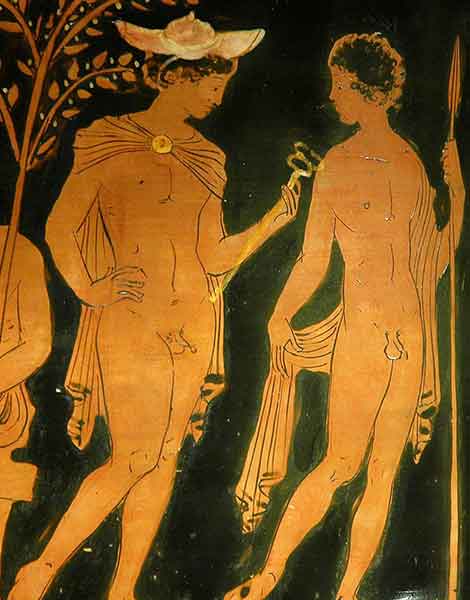

Niobid Painter - Red-Figure Amphora with Musical Scene, ca. 460-450 BC.

© Walters Art Museum / Public domain

When strolling around the sculpture gallery at any one of the fabulous archaeological museums in Greece, visitors may be forgiven for thinking that ancient Greeks, especially the men, spent most of their time in the buff. Rows of life-size statues in heroic poses are often depicted semi- or fully nude, while most female figures are shown wearing light, loose-fitting dresses, evocative of year-round sunny, dry weather.

While we know that nudity was socially acceptable for men in Greek antiquity, at symposia (drinking parties) and on the athletics fields for example, clothing would have been a practical necessity in most everyday activities, especially when out hunting, riding horses, or on military service (except as a rower in the navy). During religious festivals and civic events, scholars generally agree that clothing was not optional.

This was certainly the case for women, especially those from wealthy families, who, in ancient Athens at least, were expected to be fully clothed in public, wearing long robes down to their ankles and a head covering or veil to obscure most of their face and neck. By contrast, women in Sparta, who enjoyed greater autonomy than their counterparts in other city states, could exercise wearing tightly wrapped, single-shouldered tunics, exposing more flesh.

To that end, the ancient Greeks of the Archaic (ca. 800-480 BC) and Classical (480-323 BC) periods had a number of clothing options available to them, based around two primary garments: a tunic (either a peplos or chiton) and a cloak (a himation or chlamys). These were often mixed and matched, and worn in different styles, depending on the social status of the wearer. Much of what we know about ancient clothing comes from contemporary sources and artistic depictions, including statues and vase painting.

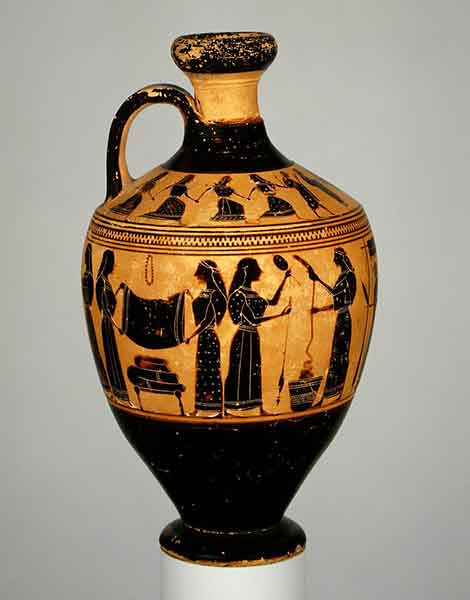

In ancient Greece, textile manufacture was largely the responsibility of women.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art / Public domain

On this lekythos attributed to the Amasis painter, women are shown folding cloth, spinning wool into yarn, and weaving cloth on an upright loom.

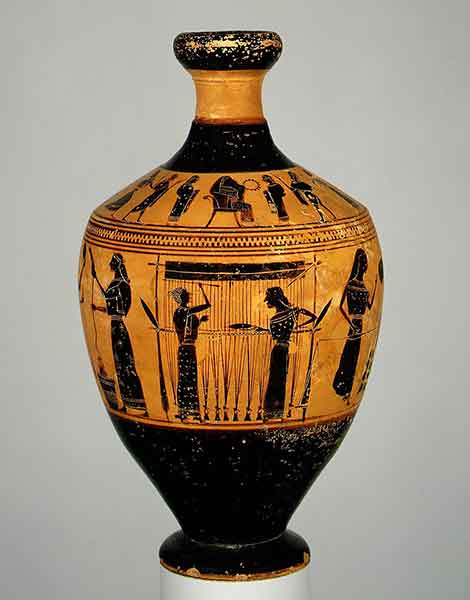

© Metropolitan Museum of Art / Public domain

While no ancient Greek clothing has survived in the archaeological record, accounts describe linen and wool as being the most common materials. The lightness of linen, woven from flax and soaked in olive oil, was ideal for the hot summers, and sheep’s wool, spun into fine threads, was used to make heavier garments, capes and cloaks for the wintertime. Finely woven linen and soft wool were more expensive, and, for the super wealthy, silk was also available.

The production of textiles was both laborious and time consuming, and generally the preserve of women and slaves. Contemporary artwork, inlcuding the traces of paint on ancient sculptures, and organic dye residues found in pottery, strongly suggest that some fabrics were brightly colored (“polychromy”) and decorated with elaborate designs. The majority of dye pigments were produced from shellfish, plants and seeds, and urine. The most expense of all, ancient writers Aristotle and Pliny both describe the creation of “royal purple” from the secreted mucus of Hexaplex trunculus, a species of murex (sea snail). Pliny even describes mixing murex and urine to create an attractive pale purple colour.

Because purple dye was extremely difficult and expensive to make, 4th century BC historian Theopompus remarked, “Purple for dyes fetched its weight in silver …” Indeed, in the Byzantine empire, a child born to the reigning emperor was said to be “porphyrogenitos,” (“born in the purple”).

Athena wearing a plain doric overfold chiton, ca. 460 BC

© Harrieta171 / Public domain

Left: A Greek youth named Kleonikos wearing a himation robe. From the Gymnasium at Eretrea, Euboea, 1st century BCE. (National Archaeological Museum, Athens). Right: Statues at the "House of Cleopatra" in Delos depict a man and woman wearing the himation

© Left: Mark Cartwright - CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 / Right: CC-BY-SA-3.0

The first item of clothing, worn by both women and men, was the chiton, a simple tunic-like garment that was formed from a wide, rectangular tube of material. It could be worn as a simple undergarment or, depending on the weather, as the whole outfit. Men’s chitons usually went to the knees and fastened around the waist with a belt (“zone”). Women’s chitons, on the other hand, were often ankle length.

Two types of chiton have been identified – Doric and Ionic, named after the two main orders in architecture. The Doric version was “sleeveless” (open on the side) and fastened at the shoulders using pins known as “fibulae.” The Ionic type was much fuller and more elaborate, with excess fabric girdled around the waist forming a pouch (“kolpos”), and sleeves that were clipped along the arms.

Peplos scene. Block V (fragment) from the east frieze of the Parthenon, ca. 447–433 BC.

© Twospoonfuls (2008) / Public domain

The peplos, a much heavier garment and mostly worn by women, was a large square piece of cloth worn over the chiton, fastened around the waist, and pinned at both shoulders, leaving it open down one side. Upper-class or aristocratic women would wear brightly colored and ornamental peploi over her chitons as a conspicuous display of wealth and status. In Classical Greek art, goddesses are often depicted wearing peploi, the most notable example bring the caryatids on the porch of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis of Athens.

The great cloak (himation), worn by both women and men, was a much heavier piece of rectangular cloth, made of linen or wool. Usually worn over a chiton (or peplos in the case of women), it was draped diagonally over one shoulder. In summer, men could wear a himation without a chiton underneath, in similar fashion to a Roman toga. A thicker woollen himation could be worn in cold weather.

Another type of short cloak worn by men was the chlamys, a seamless rectangle of woollen fabric fastened at the right shoulder with a fibula or brooch. It was mainly worn as a cape by soldiers, messengers, or servants to wealthy families (in similar fashion to a livery). A longer, heavier cloak, the red tribon, was famously worn by Spartan warriors.

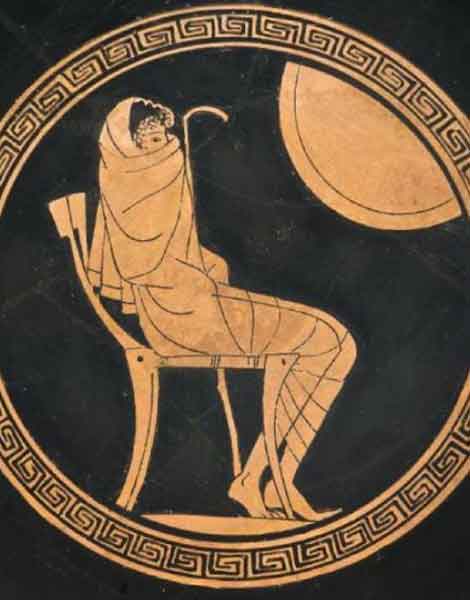

Achilles wrapped in a himation, depicted on a red-figure kylix from ca. 500 BC.

© Margareta Sjöblom (1988) / Public domain

Hermes wearing a petasos hat, Attic red-figure krater, ca. 380–370 BC.

© Marie-Lan Nguyen (2006) / Public domain

While the artistic depictions of ancient Greek clothing evoke a sense of year-round hot weather, the truth is, of course, that Greece experiences four seasons, and temperatures in the depths of winter can plunge below freezing. In fact, snow, while rare, was not unknown to the ancient Greeks, especially to those in the mountainous regions of the north, and people would have adapted with the appropriate clothing.

When moving about outside in cold weather, men and women would have worn thick, woollen cloaks and tight-fitting boots that fully covered the feet, lined with soft felt. made of wool and/or animal fur.

Accessories in the summer included a wide-brimmed hat (“petasos”), worn by men, and a peaked hat for women.

Footwear included slippers, sandals, and leather shoes, but it is thought that most Greeks walked around barefoot, especially in the house.

A monument of memory and music,...

As Greeks gather for their Tsiknopempti...

Before passports and package tours, pilgrims...

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...