There’s no getting away from the fact that the topic of ethnicity and racial identity is a proverbial hot potato. Collective memory of Nazi Germany’s weaponization of physical characteristics and national belonging in the 1930s and early 40s, not to mention some of the downright ethnocentric rhetoric from certain political groups in more recent times, can evoke a sense of unease when it comes to discussions about any one population’s physical features and ethnic origins.

More than most other populations from the ancient past, the physical appearance of the Greeks, especially those of the Classical period of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, has been a source of fascination for scholars, poets, artists, and political leaders (oftentimes nefariously), for centuries.

To put everyone at ease from the start, evidence strongly suggests that modern Greeks are genetically similar to those who inhabited these lands 2,500 years ago. Thanks to recent DNA studies of ancient human remains, we now know that today’s Greeks share a “genetic overlap” with even earlier populations in the region, being closely related to the Bronze Age Mycenaeans (ca. 1600-1200 BC) and, even further back in time, to the migrant Neolithic farmers who first ventured across the Aegean from Anatolia in the 7th and 6th millennia BC.

It’s safe to say that when we think of the descendants of the ancient Greeks, we needn’t go any further than the modern population. But beyond the typical Mediterranean stereotype of dark hair, brown eyes and olive skin that we often associate with people of Greek descent, we also know that modern Greeks are quite diverse in appearance, including those with much fairer coloring (blue and green eyes, blond hair and even the occasional redhead), and others who are much darker in complexion.

Below, we look at the available evidence to explore whether the ancients Greeks were just as diverse.

More diverse than you think

The population of ancient Greece in the Classical period, especially the city-states of Athens, Corinth, and other primary coastal centers, would have been surprisingly diverse, like many other societies dotted around the Mediterranean Basin at the time. Extensive maritime networks that crisscrossed the Mediterranean and Black Sea brought Greek seafarers and merchants into contact with all kinds of ethnic groups, and trading outposts and colonies extended their range even further. And there was also the issue of slavery and the use of mercenaries in ancient Greek warfare, which brought in migrants from the far reaches of Europe, the Eurasian Steppe and the Caucuses, as well as other parts of the Mediterranean world, North Africa and the Levant.

In order to understand what they looked like, we need to explore three main lines of evidence: how they represented themselves in art (frescoes, vase painting and sculpture), what the ancient sources say, and how these descriptions compare to more recent evidence from the study of human remains (forensic reconstruction and archaeogenetics).

Ancient Greeks in art

Greek art provides us with some important information about the physical features of people in the ancient past, although it should be noted that much of it depicts an aesthetic or perfectionist ideal. It’s no accident that numerous ancient Greek graves have been found to contain hand-held mirrors. Looks clearly mattered.

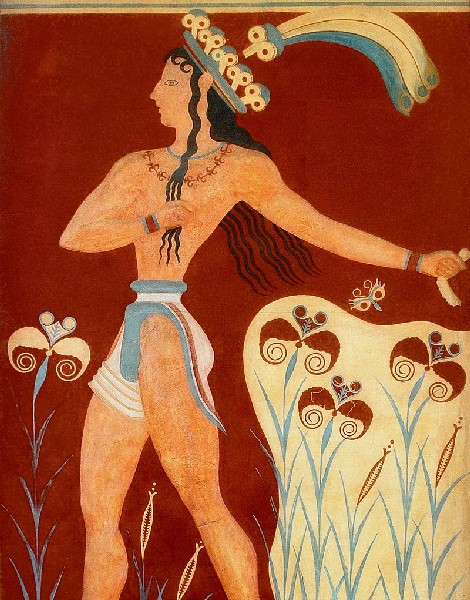

Minoan frescoes (the art of painting on plastered walls) from the mid-second millennium BC, notably from Crete and Santorini – the famous wall paintings of Thera, for example – make clear distinctions between male and female figures. Tall and slender, with narrow waists and long, dark hair, men are often depicted with reddish-brown skin, while women appear as porcelain white, with piercing kohl-rimmed eyes, and with fuller figures. This artistic convention is similar to the depiction of men and women in ancient Egyptian frescoes. In reality, Minoan women likely applied a foundation of toxic white lead or carbonate to lighten their complexion, a practice that was widely used by aristocratic women in late 16th through 18th century Europe (e.g., Queen Elizabeth I of England).

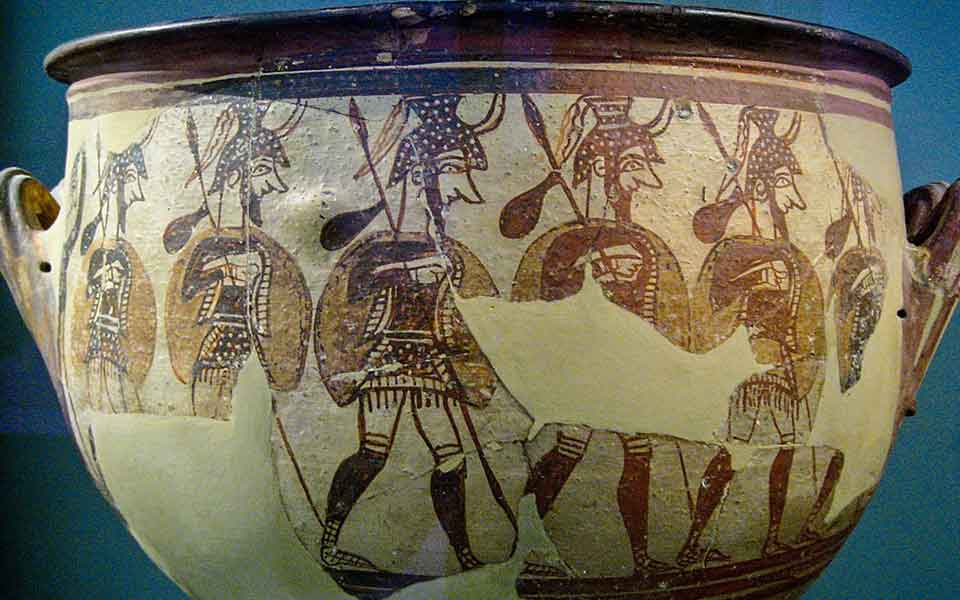

Finely painted ceramic vessels from the mid-first millennium BC, especially during the later Archaic and Classical periods (ca. 600-323 BC), provide key insight into aspects of everyday life, offering some interesting clues about the physical characteristics of everyday people. Both men and women are usually depicted with low foreheads, thick curly hair, almost always black or dark brown, straight noses, large eyes and ovoid faces. The bi-chromatic nature of the art (both in black-figure and the later red-figure traditions) makes it difficult to determine skin coloring, but the white-ground technique, developed in Attica ca. 500 BC, gave artists more freedom to express colors. In similar fashion to earlier Bronze Age art, women often appear as fair skinned while men often appear in darker hues or completely black.

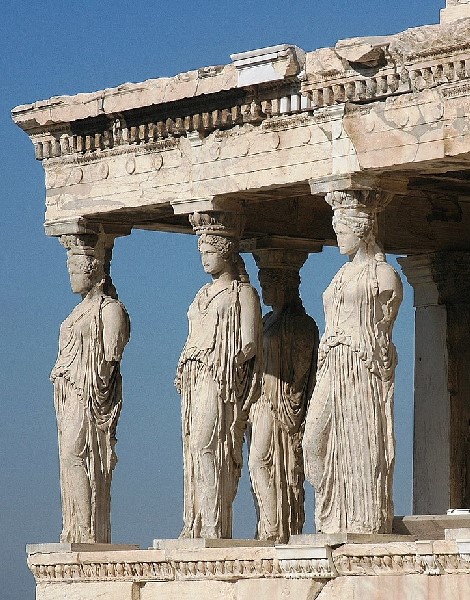

Stone, bronze and marble sculpture, arguably the Greeks’ most outstanding artistic medium, depicted ideal beauty – serene, graceful, and pious. In the Classical period, poses became more naturalistic (as opposed to the more rigid “kouroi” from the preceding Archaic era). Male figures are oftentimes shown in the nude, with a lean physique and taut musculature – the “heroic” ideal – youths appearing cleanly shaven, while older men are almost always heavily bearded. Facial features often include the same straight nose seen in vase painting, forming a straight line from base to tip, rather than a pronounced rounding over the bridge. Women, on the other hand, appear fully or partly clothed (female nudity became more accepted in the later Classical period, mid-4th century BC), and are often depicted with beautifully elaborate or intricate hairstyles (see the famous Caryatid statues from the porch of the Erechtheion temple on the Acropolis).

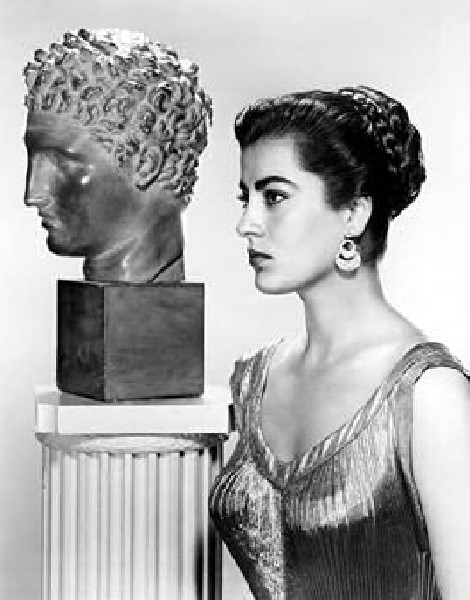

It could be argued that Alexander the Great’s thick, curly hair represents the most iconic hairstyle of any given individual from the ancient Greek world. Framing his strongly pronounced forehead and deep-set eyes, the most delicately carved marble busts were able to imitate the subtle movement of the Macedonian king’s near shoulder-length hair. It’s easy to imagine the curls gently “moving” when illuminated by flickering candlelight.

Here’s what he may have looked like in real life:

What do the ancient sources say?

Whilst ancient Greek art, in all its various forms, strived to represent the aesthetic ideal of male and female beauty, a close reading of the contemporary authors can also provide some interesting clues as to the physical appearance of the Greeks.

Amongst Homer’s many epithets in the “Iliad” and “Odyssey” (repeated adjectives or phrases linked to certain things or individuals – e.g., “wine dark sea,” “white-armed Hera,” “swift-footed Achilles”), it’s striking that many of the gods and heroes are portrayed as “golden” and “blonde-like.” Poseidon, on the other hand, is described as having a blue-black beard, while Aphrodite is “golden haired.” The term “xanthos,” meaning golden or tawny, is also ascribed to Achilles, whilst “war-like” Menelaos, the Spartan king, is referred to as “flaming-haired” or “red-haired.” We rarely think of Greeks as being blond or red-haired, but, like today, there were clearly a few kicking about in the ancient past – most definitely an exception to the rule, but certainly present. Likewise, the goddess Athena, divine counselor to the hero Odysseus, is often described as “bright-eyed” or “blue/gray-eyed” (“glaukoi”), a nod to the presence of blue-eyed Greeks.

Writing in the 5th century BC, Herodotus provides some useful descriptions of Greeks (“ethne”) in contrast to non-Greeks (“barbaroi”). While he generally accepted that Greeks were darker than northern Europeans and lighter than Egyptians and Ethiopians, his work emphasized that shared language, more than physical appearance, was chiefly important when it came to defining a collective sense of ethnic identity – Greek-speakers versus non-Greek speakers.

In his “Works on Human Nature: Mixtures,” Greek physician Galen (129-216 AD) describes the Greeks as having hair “with extremely good growth, which is strong, fairly dark, and neither completely curly nor completely straight,” while Jewish physician Adamantius Judaeus, writing in the 4th century AD, describes the Greeks as moderately tall of statue with curly hair, square faces, straight noses, and eyes “full of light.”

Human remains

Thanks to modern archaeological methods, other lines of enquiry have emerged in the study of ancient human remains. The most recent is archaeogenetics, the study of ancient DNA, which can be cross referenced with the genetic make-up of modern populations.

A recent Harvard University study, published in Nature, analyzed the ancient DNA extracted from the teeth of 19 people, including 10 Minoans from Crete (dating from 2900-1700 BC), four Mycenaeans from the Greek mainland (1700-1200 BC), and five individuals from other Bronze Age or early farming (Early Neolithic) communities (5400-1340 BC). It was found that the Minoans and Mycenaeans were closely related to each other, inheriting three-quarters of their DNA from the earlier farmers who had migrated across from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). Crucially, the Mycenaeans were found to have as much as 16 percent of their DNA from the Eurasian Steppe and/or Armenia, indicating a genetic divergence from their Minoan cousins. It appears that these northern ancestors didn’t make it as far south as Crete.

When compared to the DNA of modern Greeks, it was found there is a close “genetic overlap” with the ancient Mycenaeans, sharing many of the same ancestral roots but with some additional dilution of the earlier Neolithic ancestry. Remarking on the continuity of the modern population with their Late Bronze Age forebears, co-author George Stamatoyannopoulos of the University of Washington in Seattle, said it’s “particularly striking given that the Aegean has been a crossroads of civilizations for thousands of years.” While modern Greeks have acquired further genetic traits from later migrations, it’s no surprise that the genes for dark hair and brown eyes, carried over from the Minoans and Mycenaeans, remain so dominant today.

Yet more evidence for physical characteristics can be gleaned from the art of forensic facial reconstruction, a blend of anatomy and physiology, osteology, and, somewhat controversially, a liberal does of creative imagination.

Based on the well-preserved remains of skulls, forensic anthropologists can create two- or three-dimensional reconstructions by using the musculature of the cranium, or by overlaying facial tissue based on depth data according to race, sex and age, or a combination of the two (known as the “Manchester Method” – developed by specialists at the University of Manchester in the UK). Three standout projects in Greece have attempted to recreate the physical appearance of individuals from different periods of the past: Philip II of Macedon, a young victim of the Plague of Athens (430-426 BC), and the 9,000-year-old remains of a young woman from the Greek Mesolithic (ca. 7000 BC).

The skeletal remains of Philip II of Macedon, Alexander the Great’s father, were discovered in 1977 by Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos in the main chamber of Tomb II at Aigai, near Vergina. Assassinated in 336 BC at the age of 46, there are almost no descriptions of the king in the ancient sources beyond that he had a full beard and had lost his right eye 18 years earlier at the siege of Methone (354 BC). In the early 1980s, a University of Manchester team identified the king’s partly cremated skull on the basis of the eye injury and were able to produce two facial reconstructions.

Recovered from a mass grave in the Kerameikos in the mid-1990s, “Myrtis” was the name given to an 11-year-old girl who died of typhoid fever during the Plague of Athens in 430 BC. Myrtis’ skull was exceptionally well preserved, enabling Greek orthodontics professor Manolis Papagrigorakis to scan her facial features and build an accurate reconstruction. Myrtis’ reconstructed appearance, used in the United Nations’ “We Can End Poverty” campaign in 2011, was given brown eyes and red hair.

A more recent reconstruction by Professor Papagrigorakis in 2018, that of a young woman who lived in the Mesolithic (“Middle Stone Age”) ca. 7000 BC, used a combination of CT scans and 3D printing technology. Named “Avgi,” Greek for Dawn, and thought to be around 18 years of age when she died, her remains were first recovered in 1993 from Theopetra Cave, in the central Greek region of Thessaly. Her heavy-set features, broad forehead and protruding jaw are in stark contrast to the more finely featured Myrtis, reflecting her harsh hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Like ancient, like modern

As we have seen, recent DNA studies have confirmed that today’s Greeks share a significant “genetic overlap” with the Mycenaeans and early farmers who first arrived in this region in the Early Neolithic, ca. 7000 BC, with additional DNA from later migrations. What they looked like, however, is difficult to determine, but many of the artistic representations show them to be broadly similar to a large cross-section of the Greek population today, namely dark-haired, brown-eyed, and with fair to olive skin.

There are of course exceptions, with the odd blond-haired, blue-eyed Greek thrown into the mix, as well as other colorations, sometimes described in the ancient texts. The Thracians to the north (from modern-day Bulgaria, parts of northern Turkey and Greece), according to Herodotus, included lots of redheads. As the populations mixed, the MC1R gene for red hair diffused further southwards – hence the odd occurrence of red/auburn-haired Greeks.

People from other parts of the Mediterranean, including North Africa/Egypt, Anatolia and the Levant, also mixed with the ancient Greek population (through trade, slavery, warfare, migration), leaving behind their genetic “fingerprints,” too. In sum, the ancient Greeks were a pretty diverse lot – much like today’s population.

While much of the genetic history of modern Greece was already in place by the end of the Late Bronze Age, subsequent migrations over the millennia have left their mark.

More recent migration from other parts of Europe, Africa, the Middle East and beyond is now becoming the norm for Greece, a country at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, and the modern population is certainly reflective of that increasing diversity.