The Essential Guide to Greek Christmas Traditions

Explore Greece’s Christmas traditions, from sweet...

The Kallikantzaroi of Greek folklore are said to reside underground, emerging to the surface during the Twelve Days of Christmas, from December 25 to January 6.

© Shutterstock

As Christmas casts its shimmering glow over bustling streets and homes draped in twinkling lights, a question lingers in the winter air: Have you noticed strange noises at night, like faint scratching or low murmurs from unseen sources? Or perhaps you’ve woken to an inexplicably upturned chair, an extinguished fire, or the faint scent of something otherworldly? Beware – your festive season may not be as peaceful as you think.

You might have had an uninvited visitor – a mischievous little goblin known as a “Kallikantzaros” (plural: “Kallizantzaroi”). These supernatural creatures from Greek folklore awaken during the Twelve Days of Christmas, bringing with them a peculiar blend of mischief, mayhem, and dark humor. Their antics remind us that even in the season of joy, shadows still linger at the edges of the light.

Let’s dive into the fascinating world of the Kallikantzaroi to uncover their origins, popular stories, and the ways they continue to shape Greek Christmas traditions.

Small and mischievous, the Kallikantzaroi spend most of the year attempting to fell the trunk of the World Tree, hoping to bring about the Earth's total destruction.

The story of the Kallikantzaroi begins in the deep, myth-laden roots of Greek folklore. Scholars trace their lineage to ancient beliefs in chthonic spirits – malevolent beings thought to inhabit the underworld and emerge during the dark days of the winter solstice. This period, when the sun’s light wanes, was considered a time of heightened supernatural activity.

As Christianity spread through Greece, pagan customs merged with Christian traditions, transforming these spectral figures into the Kallikantzaroi we know today. The Twelve Days of Christmas – called the “Dodekaimeron” in Greek – became their playground. From December 25 to January 6, these goblins abandon their subterranean homes to roam villages and towns, leaving chaos in their wake.

According to folklore, the Kallikantzaroi spend most of the year deep underground, laboring to saw through the trunk of the mythical World Tree – a cosmic pillar believed to support the Earth. This Sisyphean task is never completed, as the goblins are compelled to ascend to the surface during the Dodekaimeron. While they revel in their seasonal escapades, the World Tree miraculously heals, forcing the goblins to start anew when they return to their underground lair after Epiphany. The futility of their efforts echoes the themes of cyclical time and perpetual struggle found throughout Greek mythology.

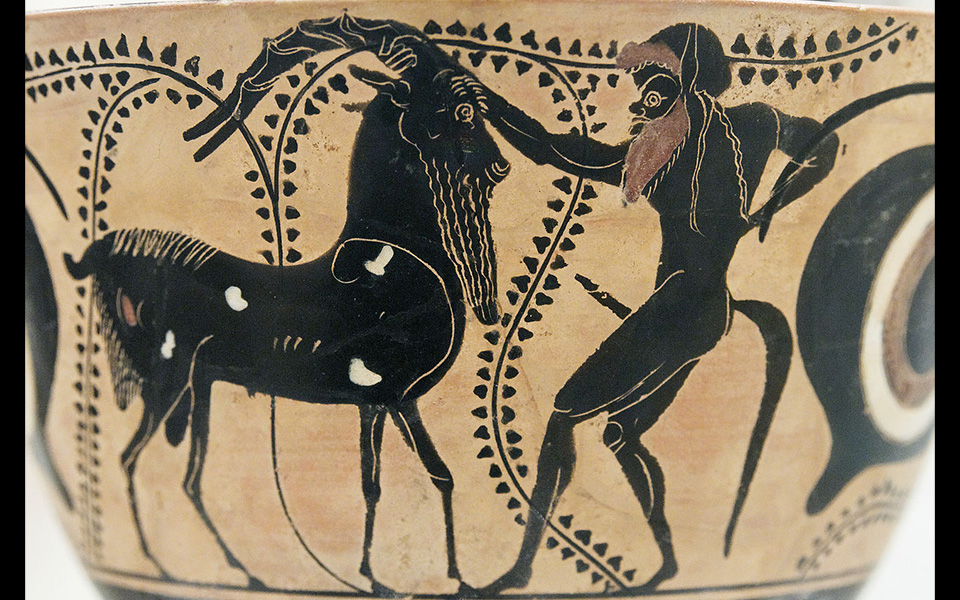

In ancient Greek mythology, satyrs were lively companions of Dionysus, the god of wine, music, and revelry.

The term “Kallikantzaroi” sparks lively debate among folklorists. Some trace it to the Greek words “kalos” (meaning beautiful) and “kantharos” (beetle or pot), hinting at a mix of beauty and grotesqueness. Others link it to “kalos-kentauros” (beautiful centaur), evoking the comically hideous satyrs of ancient Greek mythology, companions of Dionysus, the god of wine and revelry.

While similar goblins appear in the folklore of other neighboring cultures – like the dreaded (and significantly more terrifying) Krampus of Alpine tradition – the Kallikantzaroi remain uniquely Greek, entwined with the country’s rich tapestry of Christmas customs.

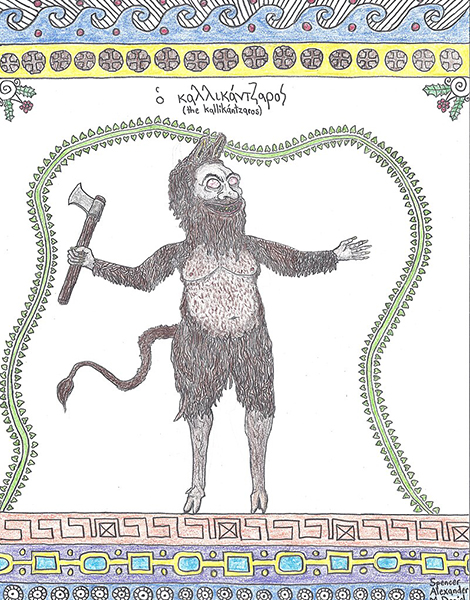

Pencil illustration from 2020 depicting a hairy kallikantzaros with goat legs, donkey ears, burning red eyes, and a long tail.

© Katolophyromai

Greek primer illustration of a kallikantzaros with goat legs and donkey ears.

The Kallikantzaroi are as weird and grotesque as they are fascinating. Imagine small, hunched figures with coarse, hairy skin, goat-like legs, and sharp claws that gleam in the firelight. Their glowing eyes pierce the darkness, and their twisted, animalistic features give them a truly otherworldly appearance. Some tales describe them as lisping and blind, with a penchant for feasting on worms, snails, and other unappetizing creatures.

Yet for all their fearsome looks, the Kallikantzaroi are more prankster than predator. They delight in petty mischief. Their favorite activities include souring milk in village homes, extinguishing fires, and spilling ash from hearths across freshly cleaned floors.

They are said to slip into houses through chimneys, cracks in walls, or even open windows. Their antics, though frustrating, are rarely harmful, earning them a reputation as impish nuisances rather than malevolent beings.

According to folklore, just as the final section of the World Tree is about to be sawed through, Christmas dawns, allowing the Kallikantzaroi to emerge from the depths.

The most iconic tale of the Kallikantzaroi is their futile endeavor to fell the World Tree, thus causing the Earth to collapse in on itself. This narrative, with its cyclical rhythm, captures the essence of their existence: creatures doomed to an eternal dance of toil and frivolity.

One beloved Greek fairy tale about the Kallikantzaroi recounts the story of two sisters, Kallo and Marbo. In the tale, Kallo is sent to the mill at midnight and encounters the goblins. Using her wit, she tricks them into fetching her jewels and beautiful dresses. By dawn, the goblins are forced to retreat, leaving Kallo unscathed and richly adorned. Marbo, envious of her sister’s success, attempts the same but lacks Kallo’s cunning. Instead, she falls victim to the goblins’ pranks, returning home humiliated.

This tale highlights the dual nature of the Kallikantzaroi: dangerous yet susceptible to human cunning.

Despite their fearsome looks, the Kallikantzaroi are more trickster than predator.

© Shutterstock

In Greece, the Twelve Days of Christmas are celebrated with a mix of joy and caution. This period, spanning from December 25 to January 6, is often referred to as the “unbaptized days” in Christian tradition – the time from the Nativity to the visit of the Magi, or Three Kings. The Kallikantzaroi are believed to be most active during this period, leading to a range of customs and rituals aimed at warding them off.

A favorite among Greeks is to hang garlic at entryways, its pungent smell believed to repel the goblins. Another fascinating custom involves leaving a colander by the door. According to legend, the Kallikantzaroi are compelled to count the holes in the colander, but their inability to count beyond two – three being a sacred number – ensures they are caught in this futile task until the first rays of dawn chase them away. Other customs include lighting fires in hearths throughout the Dodekaimeron to prevent the goblins from entering through chimneys and drawing crosses with charcoal on doorways for spiritual protection. In some regions, families hang a basil-wrapped cross over a bowl of holy water, using it to bless each room daily.

Food plays a central role in Greek Christmas traditions, and even the Kallikantzaroi have found their place at the table. Families sometimes leave out offerings of “loukoumades” – golden, honey-soaked doughnuts – as a distraction for the goblins, who are drawn to their sweetness.

The Blessing of the Waters on the Feast of Epiphany, January 6th.

© Shutterstock

As the Twelve Days of Christmas draw to a close, the Feast of Epiphany on January 6 brings a climactic end to the goblins’ antics. This day holds profound spiritual significance in the Greek Orthodox Church, commemorating both the Magi’s visit to the infant Jesus and His baptism in the Jordan River. On Epiphany morning, priests bless homes and public spaces with holy water, banishing the Kallikantzaroi back to their subterranean lairs.

In some regions, young men participate in the “Blessing of the Waters,” diving into icy rivers or seas to retrieve a cross thrown by the priest, symbolizing purification and renewal. For many Greeks, this marks not only the goblins’ departure but a spiritual reset – a return to order after the chaos of the unbaptized days.

While belief in the Kallikantzaroi has faded in urban areas, they remain a beloved part of Christmas folklore in many parts of rural Greece. Stories about the goblins are passed down to children, fostering a connection to cultural heritage, and providing playful lessons about consequences and behavior. Local theater performances and festive decorations often feature these mischievous creatures, adding humor and whimsy to the festive celebrations.

More recent interpretations of the Kallikantzaroi sometimes portray them as misunderstood outcasts rather than outright villains, adding depth to their character. This mirrors broader trends in folklore, where traditionally fearsome figures are reimagined as complex, relatable entities.

Beyond their antics, the Kallikantzaroi symbolize the tension between chaos and order, darkness and light. They reflect humanity’s desire to explain the unknown and find balance in a world filled with both mischief and wonder.

So, as you light your hearth and hang your garlic this Christmas, remember the Kallikantzaroi and the magic they bring to Greece’s winter nights. Mischievous yet endearing, these goblins are a testament to the enduring power of folklore, connecting generations through stories of laughter, wonder, and festive mischief. Who knows? They might pay you a visit this holiday season – but only for a harmless prank or two.

Explore Greece’s Christmas traditions, from sweet...

A Polish-born artist who lives on...

From Christmas markets to New Year’s...

From epic battles to avant-garde tragedy,...