The air is thick with smoke and the deafening roar of cannon fire. A relentless storm of artillery darkens the sky as waves of Ottoman janissaries surge toward the shattered walls of Rhodes, pouring through an 11-meter-wide breach near the bastion of England – the scene of the bloodiest fighting. For six brutal months, the Knights of the Order of St. John have held their ground, vastly outnumbered but unyielding. Clad in heavy armor, their red surcoats emblazoned with white eight-pointed crosses, they fight with desperate valor, their swords flashing in the chaos.

Above the carnage, Grand Master Philippe Villiers de L’Isle-Adam watches from the ramparts, his gaze fixed on the battlefield below. He knows the end is near.

It is December 1522, and Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent’s vast army has breached the final defenses. With food and ammunition dwindling, the once-mighty stronghold of the Knights is on the verge of collapse. Though they have inflicted staggering losses – some sources claim as many as 73 enemy deaths for every one of their own – the tide of war is unstoppable. Bloodied and exhausted, the defenders lay down their arms at last, marching out of the city with honor as the banners of the Ottoman empire rise above the smoldering ruins. After more than two centuries, the Knights of Rhodes are no more.

And yet, their legacy endures.

© Shutterstock

Rhodes, the largest of Greece’s Dodecanese islands, is a place where history isn’t just remembered – it lives and breathes. Step through the massive stone gates of the Old Town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and suddenly, you’re walking in the footsteps of these warrior monks. The cobbled Street of the Knights still echoes with their presence, while the Palace of the Grand Master stands as a testament to their lost Aegean empire.

For over two centuries (1310 to 1522), the Order of the Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitallers, transformed Rhodes into one of the most formidable Christian strongholds in the eastern Mediterranean. They built vast fortifications, defended against relentless sieges, and policed the high seas against Barbary pirates and Ottoman war fleets alike. Theirs is a story of faith, war, and survival – a tale etched into Rhodes’ mighty walls and whispered through its labyrinthine streets.

So, step back into the age of chivalry as we uncover the Knights’ dramatic rise and fall, explore their architectural marvels, and journey through one of Europe’s most breathtaking and best-preserved medieval cities.

Poverty, Chastity, and Obedience

Before they were warriors, they were healers.

The Order of St. John began as a brotherhood of Benedictine monks devoted to caring for weary pilgrims in the Holy Land. Their origins trace back to the 11th century – as early as 1023, according to the chronicler William of Tyre (c. 1130–1186). Their first great mission was the operation of a hospital in Jerusalem, offering shelter and medical aid to Christian travelers braving the perilous journey to the sacred city. But in a land ravaged by near-constant war, especially after the expansion of the Seljuk Turks in the Levant, compassion alone was not enough.

The success of the First Crusade (1096–1099) reshaped the Order’s destiny. In the wake of the Christian reconquest of Jerusalem, the Hospitallers evolved from a charitable order into a military brotherhood, sworn to defend Christendom and provide armed escorts for pilgrimages. Their formal establishment came in 1113, when Pope Paschal II recognized the hospital as an independent entity under the Church, exempt from both secular and local ecclesiastical authority.

Like their counterparts – the Templars, Teutonic Knights, and other chivalric orders – young men from noble families across Western Europe, drawn by the ideals of chivalry and the ethos of the Crusading movement, flocked to join their ranks, taking sacred vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The Hospitallers, however, retained a dual identity: they were both warriors and caretakers, tending to the sick and wounded even as they fought on the front lines.

By the 13th century, the Order had become a military powerhouse, commanding well-trained knights, mighty fortresses (including the impenetrable Krak des Chevaliers in Syria), vast estates and priories across Europe, and a formidable naval fleet that patrolled the eastern Mediterranean.

From humble beginnings, these warrior monks had evolved into one of the most elite fighting forces in the medieval world, answerable only to the Pope.

But the tides of war were shifting.

In Search of a New Home

In 1291, following decades of relentless attacks and petty in-fighting, the last great Crusader stronghold in the Levant – Acre – fell to the Mamluks, marking the final collapse of Christian rule in the Holy Land. The Knights, now homeless, retreated to Cyprus, where they regrouped – first under Grand Master Guillaume de Villaret, and later under his nephew, Foulques de Villaret. But Cyprus was a fragile refuge, surrounded by hostile powers and plagued by internal strife. The island offered little security for the Order’s future.

The Hospitallers needed a new home. A fortress. A kingdom of their own.

Their gaze turned to Rhodes, a strategic jewel at the crossroads of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. To control Rhodes was to control the trade routes between East and West, positioning the Knights as a dominant force in the Mediterranean.

But seizing the island would not be easy. The Byzantine forces, backed by armed Genoese merchants, held Rhodes with a firm grip, resisting the Knights’ advance. The battle raged for several years, marked by fierce naval clashes and relentless sieges. Yet the Hospitallers, hardened by decades of war in the Levant, proved unstoppable. In 1310, they finally claimed Rhodes as their own, establishing a sovereign stronghold – one that would endure for more than two centuries.

But to hold Rhodes, the Knights needed more than swords and ships. They needed a fortress city, one capable of repelling the full force of an empire.

Turning Rhodes into a Fortress

When the Knights of St. John seized Rhodes, they inherited a city that was already fortified – but not nearly strong enough to withstand the might of the empires that loomed on the horizon: the lingering albeit fractured Byzantines, the Mongol Ilkhanate in Asia Minor, the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria, and a new Turkish power that would soon become the Ottoman empire all cast long shadows over the eastern Mediterranean. If the Knights were to hold their new home, they needed more than just walls – they needed an unbreakable stronghold.

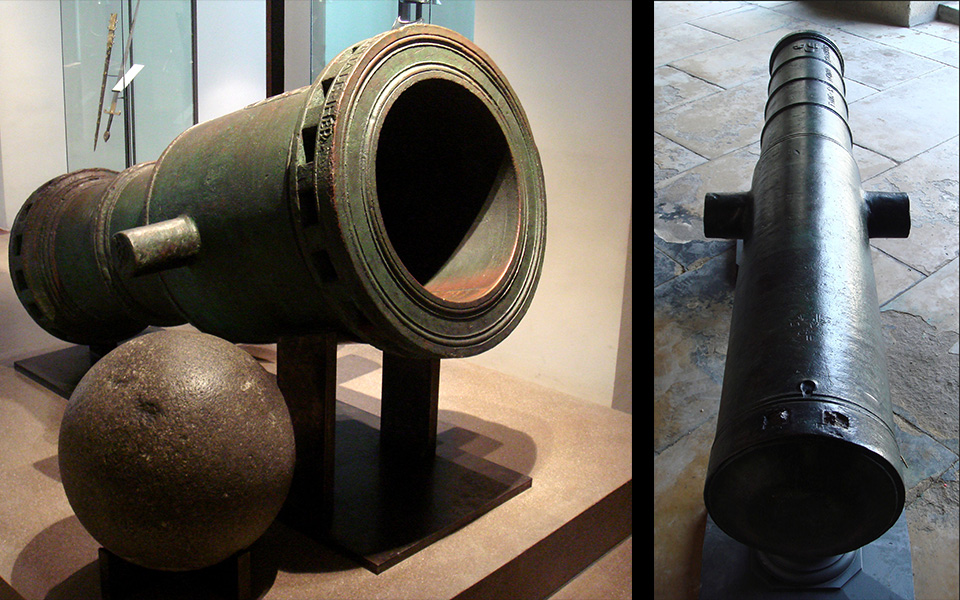

The Hospitallers launched an unprecedented military transformation, turning Rhodes into one of the most impregnable fortresses of medieval Europe. The city’s existing Byzantine defenses were not merely reinforced but radically expanded. Massive stone bastions, deep moats, and multilayered ramparts were constructed, designed to endure both prolonged sieges and the devastating impact of early cannon warfare. The most skilled military engineers of Christendom, trained in the latest European siege techniques, oversaw the project. Towering watchtowers and bastions – each assigned to a different Langue (or “Tongue”) of the Order – ensured that every approach to the city was heavily defended.

The result was an engineering marvel. The fortress walls, still standing today, stretch nearly 4 km around the Old Town. At points, they reach a thickness of 12 meters, and in particularly vulnerable sections, they were doubled or even tripled for added strength. Encircling it all was a deep moat, a final deadly obstacle for any would-be invader.

© Shutterstock

At the heart of this mighty citadel stood the Palace of the Grand Master – a colossal Gothic stronghold built in the 14th century atop the ruins of an earlier 7th-century Byzantine fortress. More than a military command center, the palace was the seat of the Grand Masters, a place of diplomacy, governance, and strategic planning. Within its massive stone walls and defensive towers, decisions were made that shaped the fate of Rhodes and its defenders.

Though the palace was partially destroyed by an explosion in 1856, it was meticulously restored by the Italians in the late 1930s during their occupation of the Dodecanese. Today, it stands as one of the finest surviving examples of medieval fortress architecture, its ornate halls and medieval artifacts offering a glimpse into the island’s storied past.

Multilingual Stronghold

Just beyond the Palace of the Grand Master, one of the best-preserved medieval streets in the world stretches toward the harbor – the legendary Street of the Knights. This cobbled thoroughfare, lined with imposing stone lodgings and intricately carved coats of arms, was the heart of the Order’s international brotherhood. It housed the “Inns” of the Order’s eight Langues (or “Tongues”), the distinct ethno-linguistic divisions that formed the backbone of the Knights’ organization, each represented in the Order’s eight-pointed cross.

Each Langue represented a different group of knights, bound by language, heritage, and shared military duties. The eight original Langues were: Aragon, Auvergne, Castile, England, France, the Holy Roman Empire, Italy, and Provence.

Every Langue was administered by a Prior and had its own quarters, chapel, and defensive responsibilities within the fortress city. Though French, Latin, and Italian were the official written languages of the Order, the spoken language of daily life in Rhodes was a kind of medieval “Esperanto” – a blend of Italian, Spanish, and French, used alongside various dialects of medieval Greek, reflecting the diverse origins of the Knights and the island’s cosmopolitan inhabitants.

© Perikles Merakos

The walled city of Rhodes was divided into three distinct sectors, each serving a unique function within the Order’s stronghold. At the highest point stood the Administrative Quarter, dominated by the Palace of the Grand Master, where the Order’s leadership resided and governed the island. Below it lay the Kollakio, the domain of the Knights themselves, where the various Langues maintained their Inns and lodgings, each adorned with heraldic emblems reflecting their distinct national identities. Beyond these elite quarters stretched the Bourgo – or “Hora,” as it was known in Greek – the lower town where the Greek and Jewish communities lived alongside the Catholic “Franks,” a catch-all term used for Latin Christians.

While the Knights ruled from their fortress above, life in the Bourgo thrived in the shadow of the city’s mighty walls, a testament to Rhodes’ diverse and multicultural past.

Fortress Island

But the city itself was just the beginning.

Beyond the fortified walls of Rhodes Town, the Knights constructed 11 castles across the island, including Monolithos and Kastellos, securing key strategic points and protecting the 50 villages that lay beyond the capital. Even the harbor was fortified, with a massive, submerged chain that could be raised to block enemy ships from entering the port. Every inch of the island was turned into a military-monastic state, a bulwark against the ever-expanding power of the Ottoman Turks.

And soon, their defenses would face the ultimate test.

The Sieges of Rhodes: The Knights’ Finest Hours

For more than two centuries, the Knights of St. John held Rhodes as an outpost of the Christian West on the doorstep of the Muslim world. Their presence was a constant thorn in the side of the Ottomans, who viewed the island as both a strategic prize and an obstacle to their naval dominance of the Mediterranean.

Again and again, the Ottomans tested the Knights’ defenses, but it was in two colossal sieges – separated by just over four decades – that the Order’s legend was truly forged.

The Siege of 1480: A Miracle Defense

By the late 15th century, the Ottoman empire had reached the zenith of its power. Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople (1453), had turned his sights to Rhodes, determined to crush the Hospitallers and extend Ottoman control across the Aegean Sea. In May 1480, he dispatched an enormous invasion force of 70,000 men, led by Gedik Ahmed Pasha, to seize the island.

Inside the city’s formidable walls, only 600 knights and around 2,000 Greek and Latin men-at-arms stood ready to resist the full might of the Ottoman war machine. The odds were grim.

For three months, the attackers bombarded the city’s defenses, battering the walls with artillery fire and launching relentless assaults against the bastions. The fiercest fighting took place at the St. Nicholas Tower, a key defensive position overlooking the harbor, where the Knights and local militia fought hand-to-hand, repelling repeated Ottoman charges.

On July 27, the Ottomans launched their most ferocious assault, breaching the defenses near the Gate of St. Athanasius. The city seemed on the brink of collapse – until Grand Master Pierre d’Aubusson led a final counterattack in person, rallying the defenders and driving the invaders back from the breach. Wounded five times and barely clinging to life, d’Aubusson became a symbol of defiance and heroism.

With heavy losses and no reinforcements from Constantinople (now Istanbul), the Ottoman forces abandoned the siege on August 17. Against all odds, Rhodes had survived. It was one of the most astonishing defensive victories of the Middle Ages, and for a time, it seemed as though the Knights were truly invincible.

But the respite would not last.

The Great Siege of 1522: The Fall of Rhodes

Four decades after their first failed attempt, the Ottomans returned – this time under the command of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, the most formidable ruler in Ottoman history. He came with an overwhelming force: contemporary sources estimate as many as 200,000 men, backed by dozens of siege cannons and mortars, and a fleet of 400 warships that encircled the island.

Against this immense army, the Knights of St. John had fewer than 7,000 defenders, including just 703 knights. But surrender was not an option.

For six months, from June 26 to early December, the defenders of Rhodes fought with unyielding determination. They used arquebuses and Greek fire, launched counterattacks under the cover of darkness, and filled every breach in the walls with a wall of steel. Yet the sheer weight of Ottoman numbers was unstoppable. Siege engineers tunneled beneath the ramparts, planting explosive charges to bring down entire sections of the walls, while relentless bombardment from massive cannons shattered the once-impenetrable defenses.

Supplies dwindled. Starvation set in.

By mid-December, the city was on the verge of collapse. Yet the Ottomans, too, had paid a terrible price – disease and constant combat had decimated their ranks. Knowing that continued resistance would bring the slaughter of Rhodes’ civilian population, Grand Master Philippe Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, urged by the townspeople, negotiated an honorable surrender. In a rare act of respect for their valor, Suleiman granted the Knights safe passage. On January 1, 1523, the last of them sailed away, accompanied by several thousand Greek and Jewish inhabitants who had fought alongside them.

The white cross of the Order was lowered from the battlements, replaced by the crescent moon of the Ottoman Empire.

Though the Knights had lost their island home of more than 200 years, they were not defeated. Their next chapter would unfold on the island of Malta, where, in 1565, they would defy Suleiman once more in a siege even more legendary than the last. Meanwhile, Rhodes entered a new era under Ottoman rule, forever shaped by the legacy of the warrior monks who had transformed it into an unshakable bastion of the medieval world.

© Perikles Merakos

© Perikles Merakos

Rhodes Today: A Living Legacy of the Knights

Though the Knights of St. John sailed away in 1523, their legacy remains woven into the very fabric of Rhodes. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the medieval city they built stands as one of the finest preserved in Europe, its Gothic fortifications, cobbled streets, and grand palaces evoking a past of chivalry and conquest. Wandering through its winding alleys, visitors can still trace the footprints of the warrior monks who once defended its walls.

The Palace of the Grand Master, with its soaring towers and massive stone stairways, remains the city’s crown jewel. Once the seat of power for the Knights, it now houses a fascinating museum that brings the medieval world to life, featuring exquisite Hellenistic, Roman, and Early Christian mosaic floors, intricately carved furniture, wall hangings, and hand-woven textiles. Nearby, the Street of the Knights – arguably the best-preserved medieval street in existence – still bears the heraldic emblems of the eight Langues, a testament to the Order’s diverse European roots.

Another remarkable site within the walled city is the Church of Our Lady of the Castle (“Panagia tou Kastrou”), an 11th-century Byzantine church later transformed by the Knights into a grand three-aisled Gothic place of worship. Its blend of Byzantine and Gothic elements serves as a striking symbol of Rhodes’ layered history.

The Hospital of the Knights, today home to the Archaeological Museum of Rhodes, echoes the Order’s original mission of care. Inside, medieval weapons, ancient sculptures, and relics from the Knights’ era are displayed alongside artifacts from earlier periods, offering a deep dive into Rhodes’ rich past. Meanwhile, the imposing city walls and fortified gates, once battered by Ottoman cannons, now provide breathtaking views over the harbor and the shimmering Aegean beyond.

Where are the Knights Now?

Though their days as warrior monks have long passed, the Knights of St. John – now known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta – continue their mission in a different form. No longer a military force, the Order has traded swords and armor for medical equipment, evolving into a global humanitarian organization. As a Catholic lay religious order, it provides medical aid, disaster relief, and social assistance in over 120 countries.

Despite losing Rhodes in 1523 and later settling in Malta, the Order retained its sovereign status. Today, it is a recognized subject of international law, issuing passports, maintaining diplomatic relations with more than 100 countries, and holding permanent observer status at the United Nations since 1994. With its headquarters in Rome, the Order now operates through a vast network of 52,000 doctors, nurses, auxiliaries, and paramedics, supported by 100,000 volunteers worldwide.

© Shutterstock

Yet Rhodes is more than just a medieval time capsule. Beyond the Old Town, the island boasts sun-drenched beaches, turquoise waters, and a vibrant nightlife that draws visitors from around the world. In summer, the streets are lively with travelers exploring the fortress-city by day and dining under the stars by night. But for those seeking a quieter, more immersive experience, the shoulder seasons of spring and autumn offer a chance to wander Rhodes’ historic streets without the crowds, with pleasant weather and a slower, more contemplative pace.

The story of the Knights is not just confined to the past – it lingers in the city’s stones, its traditions, and its enduring spirit. Whether standing atop the battlements, gazing out over the sea where Ottoman warships once gathered, or simply sipping a coffee in a centuries-old square, visitors to Rhodes are not just witnessing history; they are stepping into it.

Are you ready to walk in the footsteps of the Knights?