Santorini Beyond the Crowds: What to See and...

Discover hidden beaches, authentic tavernas, ancient...

Babis the bus driver with his wife, Artemia, and his daughter, Evangelia, in 1979.

Right, mother and daughter are pictured today in the same bus.

© Left: Pamela Browne Right: Perikles Merakos

Artemia says she can’t remember exactly when photographer Pamela Browne took the family portrait inside her husband Babis’ American-made bus. She does, however, remember having to move from Mesa Gonia to Oia around 1970, when Babis got the concession to operate his bus along with a small subsidy because it was the only vehicle available to serve the residents of the remote upland village. Apart from its regular runs, Babis’ bus was also used to take patients to hospital and kids to and from the secondary school in Fira, as well as to bring in groceries and anything else that was missing in the village, along with the post. During the 1970s, Babis, who drove two scheduled runs a day, often also had to bring the midwife from Fira when a resident went into labor. Oia really was the end of the line.

Like many Australians, Pamela Browne decided to travel the world after finishing university. It was the mid-1970s and she was crossing Yugoslavia by train on her way to Budapest when she met a man named Stelios, who spoke to her about a place he said was like no other: Oia in Santorini. Her timeline is a bit fuzzy after 40 years, but she remembers keeping in touch with the young Greek, and later, in 1977, traveling from Piraeus to Santorini with Stelios and his sister on a liner called the “Miaoulis.” The journey was calamitous; engine breakdowns meant it took 48 hours in a vessel reeking of cigarette smoke and the results of seasickness. They stopped for coffee and breakfast with a view of the caldera as soon as they arrived and then took Babis’ bus, throwing their backpacks onto the roof rack. “Traveling with little old ladies and chickens, we reached Oia, after surviving the hairpin bends along sheer cliffs at breakneck speed,” Pamela recounts in the introduction to the art book “Oia: Portrait of a Village 1977-1979,” containing her photographs from that time.

Snapshot of locals playing with an octopus.

© Pamela Browne

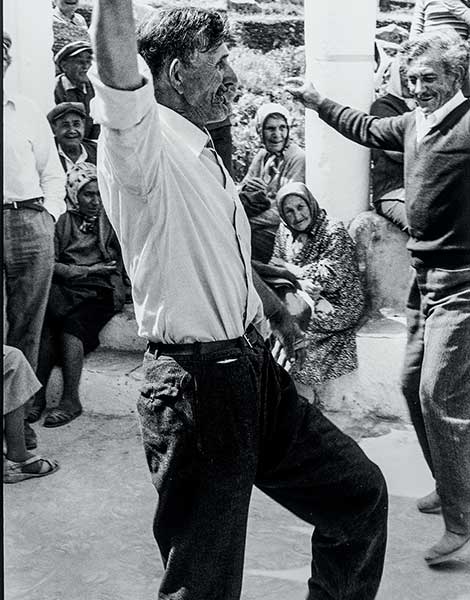

Locals dancing during the religious festival of Saint George in Oia.

© Pamela Browne

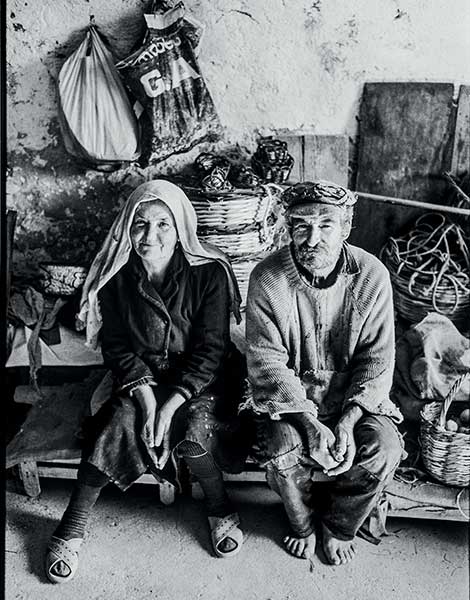

Basket-makers Charis and Roussetos in Baxedes.

© Pamela Browne

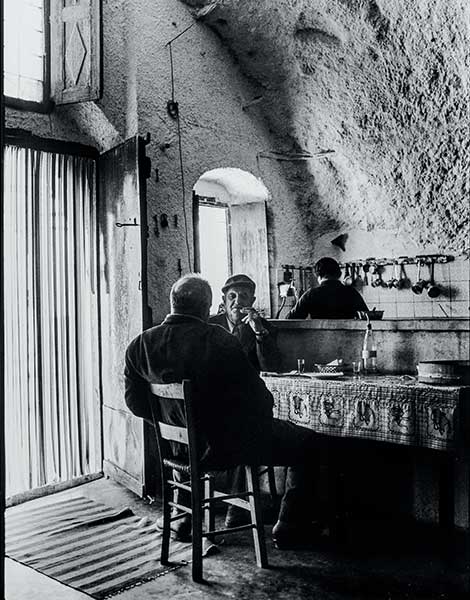

It was late autumn, almost winter, with the setting sun casting its orange glow across the village’s white houses, when Pamela realized that there was indeed “something magical” about Oia. She stayed on for 10 months, renting a room on the Armeni steps from the owner of the kafeneio Lauda, which served coffee, omelettes and occasionally canned food. The kafeneio had no fixed prices; you just paid what you could. In the summer, the owner would sometimes rent out his rooftop as well as a few rooms nearby. The village already had a small community of expatriates, mostly Germans from Stuttgart. Pamela also met a French woman, Maria Viard, who had moved to Oia from Burgundy in 1974 after coming to the island, she says, “by accident.” Viard, whose nickname is Baba Vida, ended up buying and fixing up an old building in Finikia and still lives in Oia. There were few foreigners living on the island then, and Pamela got to know them all within a couple of weeks. (Strangely enough, the village also had a monkey someone had brought over from Africa.)

The locals, most of them poor, were very friendly and would give the foreigners fruit and vegetables or treat them to a coffee as they returned from their fields on foot or by donkey. Donkeys were used for everything, including carrying heavy sacks of flour and sugar, and even barrels of gasoline for the bus. The kafeneio in the village belonged to Manolis Darzentas; it was close to the road that leads to where everyone goes to watch the sunset today. The main road also had a butcher’s shop, which today is a bar called either Hassapiko (after the Greek word for “butcher’s”) or Marykay’s. There was a baker called Nikos, two greengrocers, one run by Vintsenza and one by Georgia, and a grocery store belonging to Kallitsa in a space that‘s now a clothing store. They sold canned food, toilet paper, condensed milk, fresh eggs and, on occasion, some cheese. There was no running water, so the locals collected rainwater in cisterns and boiled it before they drank it.

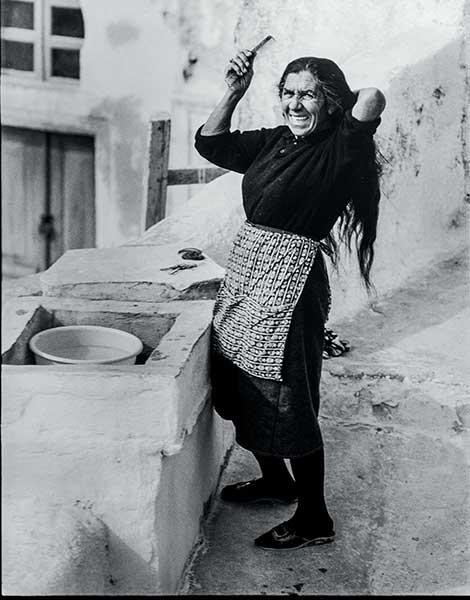

Kallitsa, owner of Oia’s grocery store, busy with her knitting.

Youngsters clambering on their father’s boat.

“We used to have lots of celebrations, and wine, red brusco, flowed freely.” Pamela remembers. The locals danced at religious festivals, including the one in honor of Saint George. “As a photographer, I always had a camera, but I didn’t walk around with it. It was hard to find film in Santorini. That said, it was easy to take people’s photographs; everyone was very relaxed. I photographed them brushing their hair and feeding their children, and I never had to convince anybody to let me photograph them. I didn’t feel like a bully when I needed to pull out my camera, as is the case now,” she says. Many of the photographs from those days will be on view in her exhibition “Portrait of a Village,” an extended version of her 1979 show, at the Oia Community Centre “Panygirospito,“ from September 7 to 14.

Conversation over coffee in the kafeneio Lauda.

Argyro, resident of the village of Finikia.

Change came abruptly to the village. In the early 1970s, the Greek National Tourism Organisation (GNTO) selected six parts of the country to develop, and Oia was one of them. “I remember my husband telling me one day that the bus just couldn’t fit so many passengers,” Artemia says. As she recounts this, she is sitting in the parking garage run by her daughter Evangelia, looking at Pamela’s photos with Maria Viard, Vassilis Mandilaras, a friend of the photographer’s, and Emily Mandilaras, who is co-curating the exhibition with Elias Cosindas. The locals are trying to put names to the faces and to recognize where these pictures were taken. In these photographs, the main road, which is now paved in white marble, has nothing but houses – no jewelry shops, no boutiques and certainly no groups of tourists.

Artemia left Oia – most natives have left – when it got a regional bus service and her sons took over from Babis. They, too, are bus drivers, but it’s no longer a one-bus town; there’s bus service from Fira every 20 minutes. The age of innocence that Pamela captured so beautifully in black and white is over. The one thing that hasn’t changed is the view: it remains equally magical, even if you have to share it with a lot more people.

Discover hidden beaches, authentic tavernas, ancient...

From Samos to Crete, we've selected...

From Santorini sunsets to ancient ruins,...