Over 5,000 years ago, nestled amidst the azure waters of the Aegean Sea, the Cycladic islands bore witness to the rise of a dynamic culture that flourished during the Early Bronze Age (c.3200-2000 BC), long before the large-scale palatial societies of Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece. This precocious island culture, sometimes referred to as the Early Cycladic Civilization, left behind a rich legacy of distinctive art, technical achievements, and the remains of highly organized settlements, comprising streets, two-storied houses, and drainage systems.

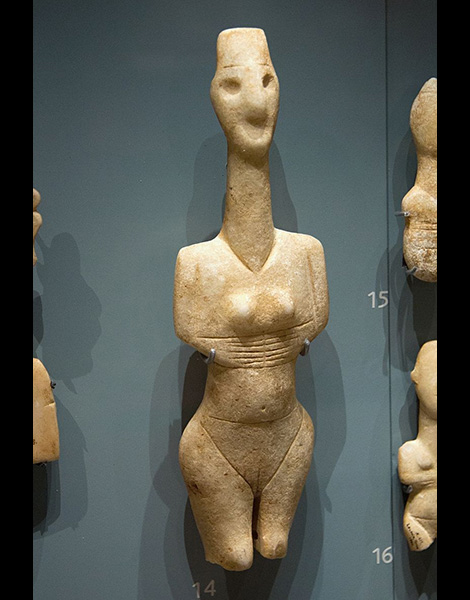

Renowned for their iconic marble figurines known as “Cycladic idols,” noted for their serene and abstract forms, and intricate pottery vessels adorned with geometric patterns, every artifact tells a fascinating story of creativity and craftsmanship, offering a tantalizing insight into the belief systems and cult practices of the ancient Cycladic people.

Here, we attempt to unravel the mysteries of Early Cycladic Culture by delving into its extraordinary art and technology, social organization, burial practices, and intricate trade networks that crisscrossed the Aegean.

For those with a serious interest in prehistoric archaeology, many of the objects left behind by this enigmatic island culture can be viewed in some of the country’s most famous museums, including the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens, home to the largest collection of Early Cycladic artifacts in the world.

© Nicholas Mastoras

Neolithic Origins

The roots of Early Cycladic Culture can be traced back to the Neolithic period (or “New Stone Age”), a time of profound social and technological change in the Aegean. Prior to the development of metallurgy and metalworking, the islands were inhabited by small-scale communities engaged in subsistence farming, animal husbandry (primarily sheep and goats), fishing, and early forms of pottery production. Tools were made from obsidian, a hard volcanic glass from the island of Milos, and local chert. Both materials could be fashioned into sharp blades, scrapers, chisels, small saws, and arrow/harpoon heads, while bone was used to make awls and needles (for stitching), and fish hooks.

During the Neolithic, which spanned from around 7000 to 3200 BC, the Cycladic islands were gradually peopled by pioneering agriculturalists who migrated from the nearby Greek mainland and Anatolia. These early settlers cultivated crops such as emmer wheat, wild barley, and pulses, adapting their farming techniques to the unique terrain and climatic conditions of the islands. Fishing, especially for tuna, also played an important role in their diet.

© Konstantinos Stampoulis - Public domain

Archaeological excavations have revealed traces of Neolithic settlements on several Cycladic islands, including Keros, Koufonisi, and Saliagos, providing valuable insights into the daily lives and material culture of the inhabitants. Neolithic communities constructed simple dwellings using locally available materials such as stone, mudbrick, and thatch. Archaeologists believe the site on the now uninhabited islet of Saliagos, occupied from 5000-4500 BC, is the oldest early farming settlement in the Cyclades. Situated between Paros and Antiparos, the tiny islet, a mere 110m by 70m in size, likely served as a center for the working and distribution of obsidian.

The Neolithic period also witnessed the ongoing development of maritime skills among islander communities, as evidenced by the presence of thousands of fishing implements and the wide distribution of obsidian throughout the region. These early mariners, using dugout canoes (hewn from a single tree trunk – “monoxylon” and bundle-reed rafts (traditional “papyrella” watercraft were used in the Ionian islands until the mid-20th century), laid the groundwork for the seafaring traditions that would characterize later Cycladic societies.

As the Neolithic drew to a close, the Cycladic islands underwent a period of cultural transformation, marked by the early development of metallurgy. Nevertheless, the Neolithic background provided the foundation upon which the Cycladic people of the Early Bronze Age built their culture, incorporating elements of agricultural innovation, maritime prowess, and material exchange into their evolving social fabric.

© Zde - Public domain

© Zde - Public domain

Island Communities

Social organization in Early Cycladic (EC) Culture was based around cooperation, reciprocity, and kinship. Like their Neolithic forbears, these tightly knit communities were predominantly agrarian, relying on subsistence farming, animal husbandry, and fishing as a primary means of sustenance. The earliest phase of the Early Cycladic (EC I – 3200-2800 BC) can be traced to the Lakkoudes cemetery on the island of Naxos.

Scholars agree that kinship networks and extended family units were at the heart of Early Cycladic society, creating a strong sense of cohesion and solidarity within individual communities. In the complete absence of written records, however, it is difficult to get any sense of the social stratification and hierarchy within these early islander settlements. Most of the archaeological evidence comes from carefully excavated cemeteries, notably in the elaborate construction of certain (high-status?) tombs and the grave goods they contain, including prestige objects such as jewelry and objects made of precious metals.

Burial customs also offer a tantalizing glimpse into the islanders’ religious/spiritual beliefs. Grave sites, often located in communal burial grounds or rock-cut tombs, and the inclusion of grave goods, including personal objects (jewelry, vessels, and tools), indicate that the islanders, at the very least, respected their dead.

© Shutterstock

By the EC II period (2800-2300 BC), cemeteries were conspicuously larger, and individual graves were often reused for several successive burials (sometimes over 20). In many cases, a small oblong slab was placed on the floor of the grave to serve as a “pillow” for the deceased. Curiously, the majority of the dead were laid to rest on their right side, in a contracted pose (fetal position), as if they were being symbolically retuned to the womb of Mother Earth(?).

Scholars have argued that the presence of presumed “ritual vases,” often zoomorphic (animal-shaped) and with no apparent practical use, may indicate some funerary or religious ritual. Others believe that the inclusion of grave goods, especially everyday objects, were intended to accompany the deceased on their journey to the afterlife, reflecting a belief in the continuity of existence beyond death.

One of the biggest cemeteries from the Early Cycladic II period was discovered at Chalandriani, on the island of Syros, attributed to the “Keros-Syros Culture” (2600-2300 BC). Here, more than 600 “beehive-shaped” graves were unearthed, organized into clusters (family groups?). Among the grave goods here were large numbers of heavily stylized, triangular marble figurines, with short, stocky legs, broad shoulders, and folded arms.

Water world

Seafaring and maritime trade played a critical role in Early Cycladic society, facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas between the islands and the broader Aegean world. According to Christos G. Doumas, Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology at the University of Athens, “the sea played a dual role: it was at once a barrier for landlubbers, invasion, influx of population, even unwanted infiltration, and a bridge for seafarers, facilitating communication with the outside world.”

Trade routes enabled the circulation of commodities such as marble, obsidian, emery, metals (copper, silver, and lead), as well as agricultural products, expanding the horizons of island communities and fostering connections with distant shores. Like their Neolithic forbears, the Cycladic people were skilled navigators, adept at traversing the sea in search of trading partners and new opportunities for exchange. Seafaring, therefore, was an important part of Early Cycladic identity.

The origins of seafaring and maritime trade in Cyclades can be traced back to the end of the Palaeolithic (“Old Stone Age”), when obsidian from Melos reached Franchthi Cave at Hermionis in the Argolid, as early as 13,000 BC, the earliest evidence for seafaring by anatomically modern humans in Greece. (There is compelling evidence that suggests archaic humans – such as Homo erectus or Homo heidelbergensis – may have crossed the sea to Crete at least 130,000 years ago.)

The introduction of metal working and the manufacture of more efficient tools would have contributed to the advancement of boatbuilding technology in the Early Cyclades. Boat representations, including the miniature lead ships in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, a rock carving from Naxos, and the incised representations of oared longboats on several frying pan-shaped ceramic vessels from Syros, indicate that Early Cycladic craftsmen were capable of building large, multi-oared vessels, sturdy enough to embark on long-distant voyages.

As trade networks expanded, so too did the cultural and economic influence of the Cycladic islands, fostering a dynamic exchange of goods and ideas. Through trade, islander communities forged contacts with the Greek mainland, Crete, and the East Aegean, contributing to the flourishing of regional communication networks and the spread of cultural innovation.

Access to fresh water would have been a primary concern for communities living on the smaller, more barren Cycladic islands, especially in times of drought. If crops failed, islanders would have been heavily reliant on neighboring landmasses for their long-term survival. As such, the eastern coastal regions of the Greek mainland have yielded copious evidence of maritime connectivity with the Cycladic world. Likewise, material exchanges with Crete can be traced to the so-called “Kampos Phase” at the beginning of EC II, initially with ceramic vessels and, later on, with Cycladic marble figurines, traded as prestige objects.