Nestled amid the sprawling olive groves of the Corinthia in the northeast Peloponnese, the ruins of the once glorious city of Tenea lay buried and undisturbed for centuries, steadily acquiring semi-mythical status.

Regarded by ancient writers, including the 2nd century AD Greek geographer Pausanias, as one of the largest and most prosperous cities in the region, Tanea was abruptly abandoned sometime after the 7th century AD, its temples, civic buildings and houses gradually falling into disrepair. Over time, its extensive street plan became entombed in thick layers of silt from nearby streams.

Despite the discovery of random surface finds over the years, the city simply vanished from view: an archaeological enigma.

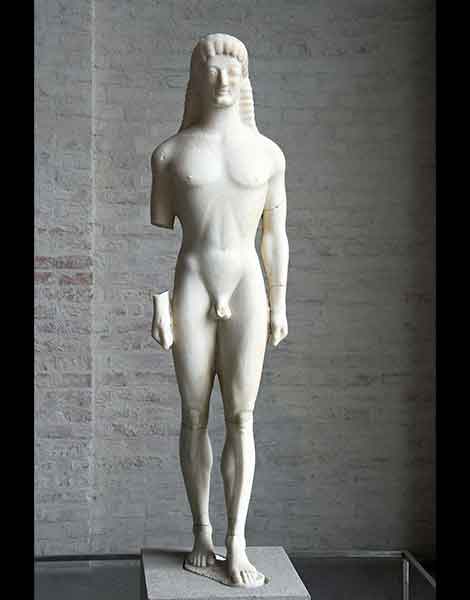

Archaeologists had long suspected the ancient city to be located somewhere in the vicinity between Corinth and Mycenae, partly thanks to Pausanias’ description of it being “about sixty stades distant” from Corinth, approximately 11km (the actual distance being around 15km). The discovery of a well-preserved marble Kouros (free-standing statue of a male nude) in the area in 1846, now on display in the Munich Glyptothek as one of the best examples of 6th century BC Greek sculpture, was another clue to the whereabouts of the site. Nevertheless, extensive agricultural cultivation in the area made it near impossible to accurately pinpoint the remains of any buildings buried under the surface.

Thanks to the chance discovery of an ancient sarcophagus near the modern village of Chiliomodi in 1984, and the unwavering persistence of Greek archaeologist Dr Eleni Korka, concrete proof of the lost city was finally unearthed in 2018, when a small but dedicated team of researchers revealed dozens of burial monuments, the ruins of houses, shops, public buildings, and the remains of a large bathhouse.

© Public Domain

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

A chance discovery

As project director and Honorary General Director of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, Eleni Korka is one of Greece’s most preeminent archaeologists. She initially dated the Chiliomodi sarcophagus, which contained the skeletal remains of a high-born woman, to the early Archaic period (late 8th-early 7th century BC), noting the exquisitely detailed paintings on the interior of the coffin. She immediately knew she was on to something.

It took nearly three decades to finally secure official permission from the Ministry of Culture to survey and excavate the area, which eventually came in 2013. With precious little funding, Korka’s small team returned to the site of the initial discovery and soon found dozens more sarcophagi in the vicinity. “Nearby we found about 40 others … they just kept coming out of the ground one after the other. It was like [the folk tale of] Ali Baba,” she told the BBC in 2019.

Moving north, beyond the ancient cemetery, the team made further important finds, including part of an ancient road and the remains of a Roman mausoleum, dated to around 100 BC, but the evidence of an actual city remained elusive.

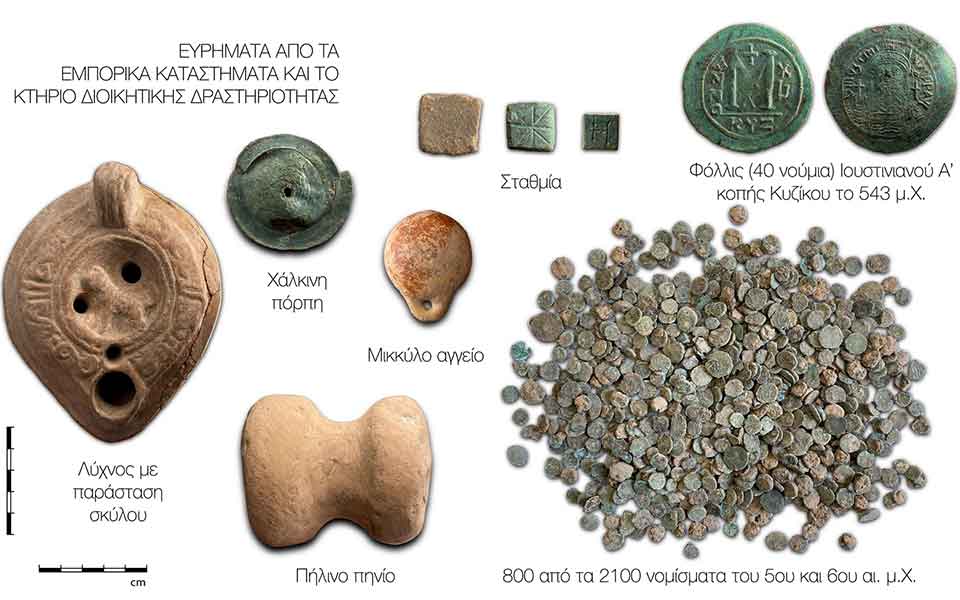

Proof finally came in 2018, when Korka identified the remnants of an extensive residential area, including paved roads, houses, water pipes, marble floors and an enormous bathhouse, dated to the end of the 3rd to mid-1st century BC. Since then, an unusually high number of coins have been unearthed – over 2,000 – many from the 5th and 6th centuries AD, including gold coins that were buried with the dead, clear evidence of the enormous wealth and prosperity of the city. Other small finds included delicately painted vases, jewellery, metal tools used to scrap off oil before bathing (strigils), and votive figurines, mainly from the later Hellenistic and Roman periods.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

Founded by Trojan captives?

According to Pausanias, Tanea was originally founded by captured survivors of the legendary Trojan War, brought to the Corinthia and “permitted by Agamemnon [leader of the Greek army and king of nearby Mycenae] to dwell in their present home.” As such, they claimed to be descended from the inhabitants of the island of Tenedos, located at the entrance to the Dardanelles, where, according to Homer, the Greeks hid their fleet to trick the Trojans into believing they had withdrawn from the war.

Acknowledging their Trojan ancestry, ancient writers tell us the Teneans were fervent worshippers of Apollo, a god who supported the Trojan side throughout the legendary war, famously inflicting a deadly plague on the Greek army.

Writing in the late 1st century BC-1st century AD, Greek geographer-historian Strabo referred to the temple of Apollon Teneatos, and mentioned that the city “prospered more that the other settlements.” He went on to write that the Teneans were left unscathed by the Romans following their destruction of nearby Corinth in 146 BC, flourished during the subsequent “Pax Romana” or Roman Peace, and that the peoples of Tenedos and Tenea shared a strong “kinship.” It is also interesting to note that the Romans, according to Virgil in his epic poem “Aeneid,” also claimed to be descended from the Trojans.

While most finds at ancient Tenea thus far date to the city’s Roman period, funerary evidence points to an extended period of habitation from the Geometric through Late Antiquity.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

The excavations continue

Despite the lockdown restrictions in 2020 and 2021 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Korka’s team continued to work on the site, unearthing more of its long-buried secrets.

Last year’s excavations brought to light for the first time the Classical-era (480-323 BC) settlement of the city, filling in a lengthy chronological gap. Excavations also revealed a large public building, covering an area of 145 square meters, with a wealth of important artifacts within its walls, including votive figurines depicting deities, birds, horses and other animals, and other Archaic and Classical-era pottery. In addition, coins of the 4th century BC were found, including Corinthian drachmas and half-drachmas.

Elsewhere, a strong defensive wall dating to the early Classic period was unearthed at the city boundary, and further burial monuments were discovered along the edge of the ancient cemetery, inlcuding a large above-ground Roman monument with an underground chamber, containing the remains of a child.

One of the unanswered mysteries is why such a large and prosperous city suddenly lost its wealth and disappeared from the historical record. Korka believes that the region may have been attacked by Slavic tribes in the 7th century AD, forcing the inhabitants to abandon their city and seek refuge in the surrounding hills.

What’s for certain is that there is so much more to discover at ancient Tenea: “It’s like an iceberg and we’re just hitting the tip,” project collaborator Konstantinos Lagos told the BBC. “It’s going to keep giving interesting findings for the next 100 years.”