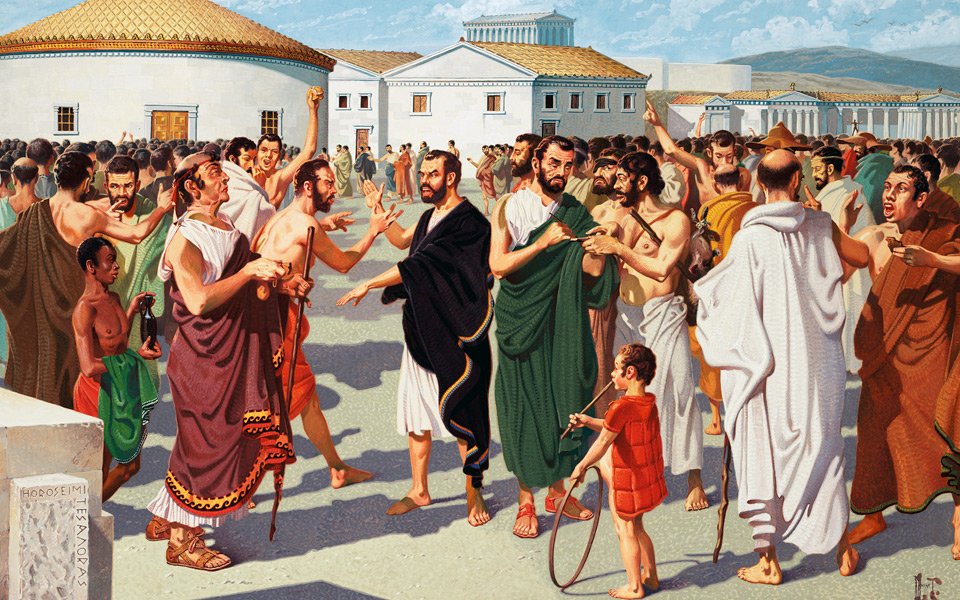

Set on gently sloping ground northwest of the acropolis, the Agora public square was laid out in the 6th century BC and has been under excavation for 85 years by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, under the supervision of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

Here have been found the buildings which housed the first recorded democracy (magistrates’ offices, law courts and assembly places), along with the objects used every day to make sure the system worked as it should (laws and regulations inscribed on stone, allotment machines, water clocks and ballots). A visitor to the Agora in antiquity would have occasion to see all three branches of the government in action: executive, legislative and judicial.

EXECUTIVE: THE ARCHONS AND THE ROYAL STOA

Coming from the main city gate, our visitor entered the Agora at its northwest corner and immediately came upon the Royal Stoa (Stoa Basileus), seat of the King Archon. There were, of course, no monarchs in democratic Athens, but the second in command was known as the King Archon; he was a powerful individual, responsible for religious matters and the laws. The stoa was his headquarters, in which he heard most of the cases brought before him. It was here, for instance, that he heard the charges of impiety laid against Socrates in 399 BC and determined that there was, in fact, sufficient evidence to send the matter to a full court of 500 jurors. The king also administered the annual oath of office to all incoming officials and magistrates, who swore to uphold the democracy and not take bribes, lest they pay a huge fine. The oath was performed at or on a massive unworked stone (lithos) which rested on the steps of the stoa. The building itself was lined with marble slabs recording in stone the constitution and laws of the city.

Like most Athenian magistrates, the king was not elected; almost all were chosen by allotment rather than election. Only a handful of positions were elective, those that required real expertise and experience: the water commissioner, some of the treasurers, as well as the generals. These roles were too important to leave to the luck of the draw. Pericles, for instance, seems never to have served as a senior archon, but showed his influence by repeated election as general of his tribe.

Whether elected or allotted, all Athenian officials were subject to an official, regular opportunity for the populace to remove a problem in the political system. A serious application of term limits, known as ostracism. Once a year the Athenians gathered in the Agora and took a simple vote: is anyone aiming at a tyranny, is anyone a threat to the democracy? If a simple majority voted yes, the people gathered again several weeks later. On this second occasion they brought with them a potsherd (ostrakon), on which they had inscribed the name of the individual they thought was a problem. The man with the most votes lost and he was exiled for 10 years. Many Athenian politicians took one of these extended vacations, courtesy of the Athenian people, and their votes, scratched onto sherds, were readily discarded and have been found by the hundreds throughout the excavations.

“ Once a year the Athenians gathered in the Agora and took a simple vote: is anyone aiming at a tyranny, is anyone a threat to the democracy? ”

© GettyImages/IdealImage

“ Once a decision had been made, the proposal was written up and posted on the face of a long statue base, the Monument of the Eponymous Heroes, which lay within the square itself, just to the east. ”

LEGISLATIVE: THE BOULE AND THE BOULEUTERION

Moving south from the Royal Stoa, the visitor would pass several buildings dedicated to gods (Zeus, Apollo and the Mother of the Gods) before arriving at the next government building, the bouleuterion. This was the meeting-place of the Boule, a council made up of 500 Athenians, chosen by lot. This may at first seem odd, but when one considers the cost, corruption, inefficiency and poor results of many modern democratic elections, it seems hard to believe we could do worse than the random choice of 500 individuals. Members of the boule served for a single year and they met most days, except during festivals, to consider and propose legislation. Once a decision had been made, the proposal was written up and posted on the face of a long statue base, the Monument of the Eponymous Heroes, which lay within the square itself, just to the east. All proposals had to be displayed for at least three days, so the citizens would have ample opportunity to read the proposal and discuss its merits. Every 10 days or so, the full citizen body met in assembly (Ekklesia) on the Pnyx, a large theatral area on the ridge to the southwest of the Agora. Here they would debate the proposal and then either approve it or vote it down. This dual passage of legislation is reflected in the opening of all Athenian laws inscribed on stone: “Approved by the boule and people (demos) of Athens”…

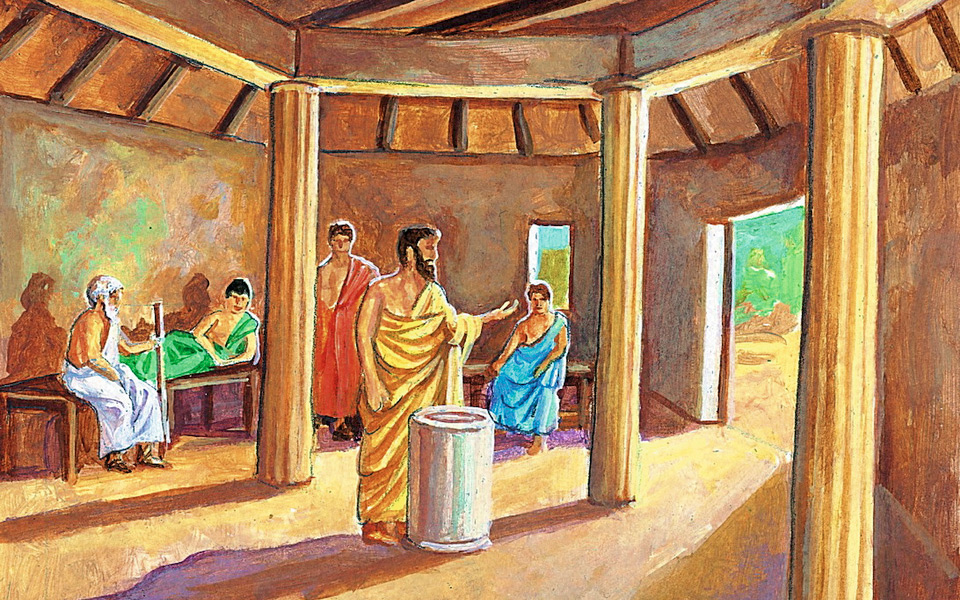

The Boule was managed by tribal contingents (prytaneis) of 50 councilors, who served in rotation for a month, acting as an executive committee. During their month in office, the prytaneis had as their headquarters the tholos, a round building just south of the bouleuterion. The prytaneis were fed at public expense and the tholos was their dining room. Cups and pitchers have been found all over the area, carrying the ligature ΔΕ, standing for demosion (public property) to make sure the prytaneis did not walk away with the state-owned crockery at the end of the meal. The fact that most of the vessels found were for wine suggests that perhaps the legislators were not always fully sober when they deliberated.

In addition to dining in the tholos, at least 17 prytaneis were expected to sleep there overnight. If some emergency arose, any messenger could go directly to the tholos to find 17 citizens serving as councilors, on duty and ready to deal with any issue. In this sense, the building represents the functional heart of the Athenian democracy, a symbolism not lost on the Thirty Tyrants who, during their brief reign in 404/403 BC, used the tholos as their headquarters.

© Corbis/Smart Magna

JUDICIARY: THE LAW COURTS

The bedrock of democracy is the legal system. Only an independent judiciary can guarantee the rights of all individuals and prevent abuses by the more powerful and privileged segments of society. The formation of the Athenian democracy was a process, not an event, and the first crucial step was taken by Solon in the 6th century BC, when he created “popular” courts, where individuals were tried by their fellow citizens, not just aristocrats or magistrates. The Athenians had many courts all over the city, at least one of which has been identified under the north end of the later Stoa of Attalos.

Because they were so essential, the courts were among the most regulated sectors of government. To ensure a fair hearing, the minimum Athenian jury was comprised of 200 citizens, while courts of 500 were not uncommon.

Elaborate allotment machines assigned the jurors to the courts so there was no way to influence an Athenian jury without bribing all of the literally thousands of citizens eligible for jury duty each year. Clepsydras (terracotta water clocks) guaranteed that each side would have the same amount of time to argue the case. And jurors were provided with two bronze ballots — one for guilty, the other for acquittal — which allowed them to arrive at a verdict in secret.

© GettyImages/IdealImage

A DEMOCRACY NOT WILDLY DEMOCRATIC

There are both parallels and differences in how democracy was practiced in ancient Athens and the modern versions of today. Ancient Athenian democracy, by today’s standards, was not wildly democratic. Excluded from participation were women, a large number of slaves and a vast population of free Greeks from others cities who lived in Athens but had no citizen rights. That is, only a small and unknown proportion of the inhabitants had a direct vote in the democratic process.

On the other hand, if you were a participant, you were expected to play an active role, to “rule and be ruled in turn” as the phrase went. Both the modern and ancient systems were flawed, but they are usually regarded as better than any of the other options. Despite any flaws, the concept of equal citizenship, the protected rights of the individual, a communal civic awareness, as well as a sense of the corporate identity of the people developed over time and led to an entirely new Athenian society, one which endured in reality for 200 years and which has remained an ideal for another 2,500.

“ Ancient Athenian democracy, by today’s standards, was not wildly democratic. ”