The French Painter Who Found his Island Muse...

Igor Borisov turned Kimolos into his...

Tinos is famed for its traditional dovecotes, which are dotted around the island.

© Sime/Visualhellas.gr

I watched her crawling on her hands and knees up the Avenue of the Megalochari, the hill leading to the entrance of the church. She looked to be about 40, a fashionably dressed woman slightly at odds with her surroundings. Then I noticed that walking alongside her, in the shadows, was a man her age and a handsome lad in his twenties, a barman perhaps, or a competitive yachtsman, or a student… who knows?

Slowly but steadily, with the sun beating mercilessly down on her, the woman reached the pebbled entrance to the Church of Panagia Megalochari (the one with all graces), entered the marble courtyard, dragged herself with some effort up the stairs along the red carpet, crossed the threshold of the church, finally stood upright on her feet, kissed the icon with warmth and reverence, lit a candle, and walked out into the revitalizing northerly breeze, to rest in the shade. She was flushed and lost in thought when I asked her, “Do you believe in miracles?”

An alley in the village of Kardiani.

© Giorgos Santamouris

A votive offering left for the safe return of a sailor.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

“But of course,” she responded. “It was a miracle that brought me here. A car accident five years ago. My boy was battling death for three months in intensive care; they had written him off. And here we are today, all together. Just look at my lad!” The young man smiled at me nervously. “And why was it the Virgin Mary who performed the miracle and not the doctors, or science?” I dared to ask. “When I had lost all hope, it was Her I pleaded with,” she answered, in a way that brooked no objection.

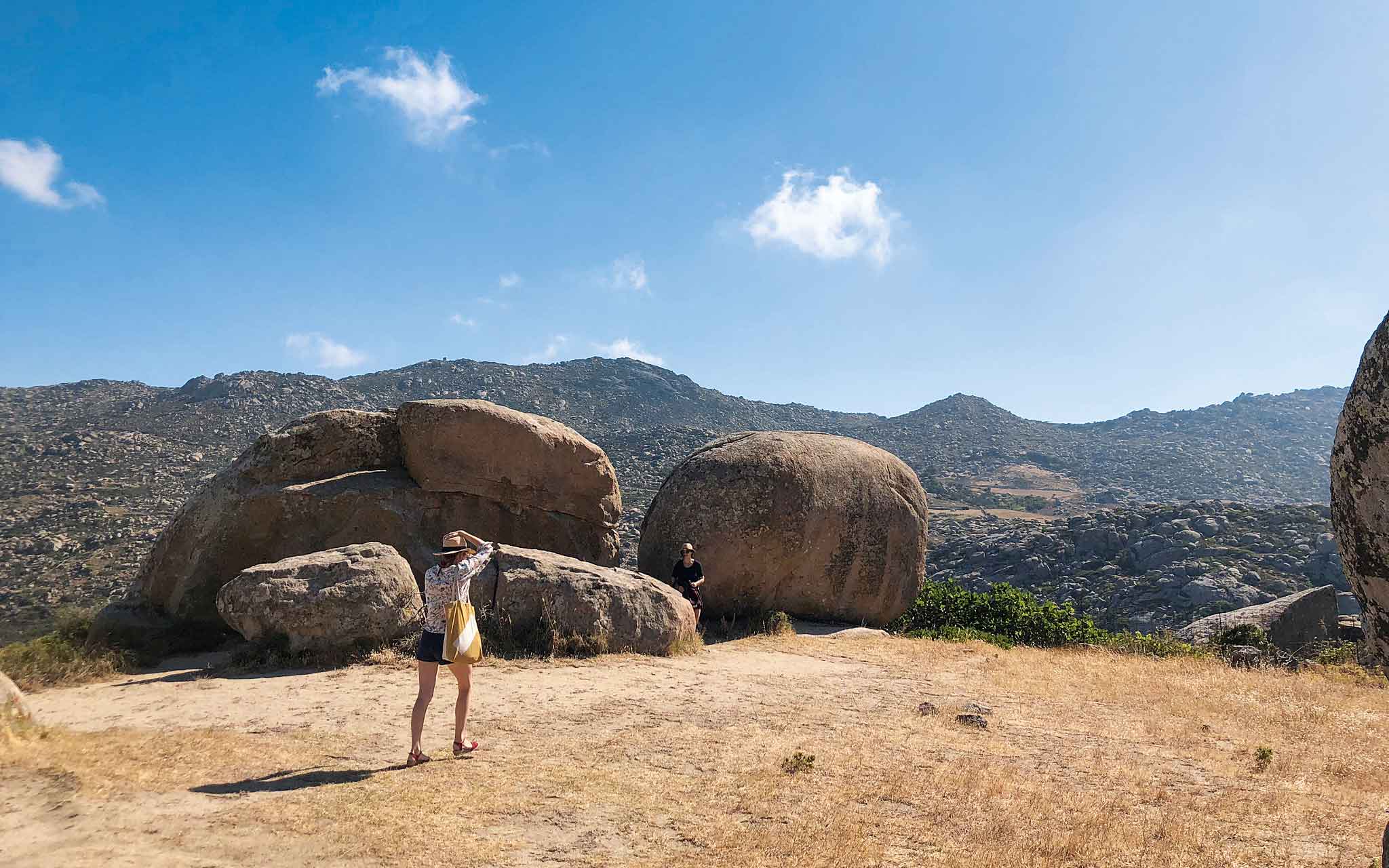

A giant granite boulder near an old threshing floor in Falatados.

© Giannis Giannelos

This is how her prayer joined those of the millions of worshipers who have been putting their faith in the Megalochari of Tinos for two hundred years now, etching, sometimes elegantly, other times artlessly, a name, a homeland, a date, on the cool marble thresholds of the church. As for myself, I won’t stop repeating that Tinos itself was saved by the Virgin Mary. It is this pilgrimage which you may find heartrending, uplifting or simply sociologically fascinating, that acted as a deterrent, rescuing the island from rampant tourist development at critical times.

Today, Tinos remains largely unspoiled (compared to other Greek islands), with villages that resemble open-air folk architecture museums. There are some contemporary award-winning buildings as well, but tradition has been spared. There’s a lively cultural life which honors both the past and the present, a farming sector undergoing a renaissance, prize-winning microbreweries and wineries, manufacturing units distributing their products nationwide, and a generation of young restaurateurs and tourism entrepreneurs who have realized that creating a destination requires vision, persistence, knowledge, and, most of all, cooperation.

© Evelyn Foskolou

Naturally, there are the beaches: otherworldly Livada with its wind-worn and salt-scarred granite boulders; Pachia Ammos with its sand dunes; Santa Margarita with its gaze on Mykonos; surfers’ favorite Megali Kolibithra; challenging Apigania; and child-friendly Laouti. But for me, Tinos is the magnificent and uniquely handcrafted hinterland.

As you approach the island from the sea, the naked, steep granite hulk of Exombourgo dominates the landscape. Like a giant eye, it observes history and human progress, oversees a wonderful rural microcosm and even defines the climate of Faltado, Koumaro, Skalado, Xinara, Arnado and all the other medieval villages which surround it. On its slopes, sometimes lost in cloud or lit by lightning, once stood the island’s capital, and on its summit perched the the Venetian fortifications, erected during Venice’s 500 years of rule. These fortifications were blown up by the Ottomans in 1715; the impressive ruins charm those persistent hikers who make their way up established routes to the peak of Aghia Eleni.

Kolymbithra Beach is popular with surfers.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

The same granite that formed Exombourgo runs towards the sea and the bay of Livada, creating in the area known as Petriados a series of uniquely beautiful landscapes. When I first came to the island, they spoke to me of the village of Volax, which gets its name from the round granite boulders scattered throughout the area. Are they the result of an ancient explosion? Or remains of a battle between the Titans and the Gods of Olympus? Fans of bouldering, who come from around the world to test their skills on these great rocks, don’t care which is true; that these stones exist is enough. Others who find their bliss in the countryside of Tinos include the hiking groups, of all ages and skill levels, who enjoy the well-marked network of Tinos Trails.

“We haven’t seen a more beautiful version of Greece,” I was told by a family on the trail towards the village of Agapi, and I agree. The farmers and herders of Tinos, artists at heart, have created with their hands and the materials at hand the landscape that we take for granted today. They built the terraces which dominate the hillsides, the dovecotes which are unique to the island, the rough shelters, the paths to their parcels of land, and, of course, the villages themselves.

There are 45 inhabited villages, all kept in outstanding condition. Most stand in naturally sheltered locations, close to potable water, in total harmony with the surrounding countryside, and with their backs, as it were, to the strong north wind.

The granite landscape of Tinos. Unique in the world, it extends from the village of Volax, curves behind Faladado, and “flows” down to the wild waters of Livada.

© Maya Tsoclis

Oh, that north wind! Tinos is famous for it, and this fact has brought a new crowd to the island: surfers, as well as aspiring surfers. On the days when the wind rages and swimmers become scarce, cars loaded with surfboards head towards Komi, and surfers from all across the world, sun-kissed and athletic, ride the waves of Megali Kolibithra.

These winds, which we often called “restorative” – I suspect for consolation – are attributed to Voreas, the son of Aeolus, and the personification of the north wind. During the voyage of the Argonauts, his winged sons, the twins Kalais and Zitis, provoked the wrath of Hercules, who hunted them down and killed them on Tinos. Since then – because everything in Greece has a mythological explanation – Voreas and old grandfather Aeolus mourn by setting the north wind on our island. Perhaps it’s these winds, and the atmosphere they create, that inspired so many creative people, from sculptors Halepas and Sohos to painters Lytras, Gyzis and my father Costas Tsoklis, and from the philosopher Kastoriadis to the composer Koumentakis, who were born here or adopted the island as their own.

They have left Tinos a notable legacy: the many cultural initiatives on offer, which attract audiences of all ages. Museums large and small, artists in residence, a plethora of local festivals and cultural initiatives, make Tinos an ideal destination for restless, mindful visitors, for those seeking to combine uplifting the soul and the spirit.

A sculptor’s studio in Pyrgos, the traditional center of marble working.

© Vangelis Zavos

The sound of hammers striking chisels echoes around Pyrgos, in Exo Meria, the northern part of the island. The land was always rich in this material, but it was the Venetian period that played a decisive role in the development of marble crafts, and the incredible Museum of Marble Crafts of the Piraeus Bank Group Cultural Foundation in Pyrgos lays out for visitors the magical journey from quarry to workshop to art collection.

Today, the centuries-old tradition of the villages of Kardiani, Ysternia, Marlas and Pyrgos continues at the Preparatory and Professional School of Fine Arts. The marble craftsmen of Tinos toil on in their workshops, using the same tools and techniques as their ancestors, some reprising traditional motifs, and others struggling to open up new artistic paths – a difficult task, under the weight of tradition.

Surfing off Livada Beach.

© Evelyn Foskolou

It’s impossible to talk about Tinos without mentioning its food and drink. The island is rightly proud of its excellent homegrown or locally made products, such as the internationally award-winning NISSOS beer and the wines from Tiniaki Ampelones vineyards, Volacus Wine, Vaptistis Winery and other worthy ambassadors who spread the message of Tinos worldwide.

Tinos’ many producers are making a name for themselves and carving out a place in the Greek market. The aged graviera and the PDO Tinos kopanisti cream cheese from the Farmers’ Cooperative, Giannis Kritikos’ cured meats, Aggeliki Rouggeri’s kariki blue cheese, and the little round cheeses of the San Lorenzo creamery are all excellent. Local restaurateurs, sensing a demand, have collaborated on gastronomic initiatives, such as Tinos Food Paths, which captured the hearts of food lovers and became models for other islands. At the forefront of this contemporary culinary scene are Marinos Souranis’ Marathia, Antonia Zarpa and Aris Tatsis’ Thalassaki, and, more recently, Dimitris Katrivesis’ Thama. With all this creativity, there’s a fear that, with the explosion of new arrivals, new chefs and new food trends, we may lose touch with the pleasures of those simple dishes which charmed us when we first came to know the island – but I’m sure we’ll prove to be wiser than that.

Ice cream on the steps with friends – a special summer treat.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Tinos is bound up in faith, in the pilgrims’ offerings, and the prayers of Orthodox and Catholics. It shines out in the spirit of the nuns of the Virgin of the Angels in Kechrovouni and the Ursuline sisters at Loutra. It is the wild goats of Tsiknias and the thyme which wafts its scent under the feet of hikers. It is the gray stone terraces of the summer and the green, flower-covered valleys of spring. It is the shadows of the clouds which rush over the island, the trees bent in the north wind, and the wild waves whipped up by the south wind.

It is the lonely beaches, the marble statuary in cemeteries, the festivals in the villages and the remote chapels, and the islanders’ flying footwork as they throw themselves into the balos, an energetic local dance. It’s the new guest houses, the award-winning restaurants, the new trails that follow ancient paths, the bookshop-cafés in the town’s alleyways, and the young fathers with babies in their arms. It is the souls of the old rejoicing in the achievements of the young, and it is the responsibility we have to hand this little paradise of ours over to the next generation, still unspoiled.

Aggeliki Rouggeri cheese, Tel. (+30) 694.825.9427

Kritikos cured meats, Tel. (+30) 22830.292.80

Marathia, Tel. (+30) 22830.232.49

Nissos beer, Tel. (+30) 22830.263.33

San Lorenzo creamery, Tel. (+30) 22830.415.49

Thalassaki, Tel. (+30) 22830.313.66

Thama, Tel. (+30) 22830.290.21

Tiniaki Ampelones vineyards, Tel. (+30) 22830.411.20

Tinos Farmers’ Cooperative, Tel. (+30) 22830.223.23

Vaptistis Winery, Tel. (+30) 22830.421.55

Volacus Wine, Tel. (+30) 697.848.5671

Igor Borisov turned Kimolos into his...

With its beautiful olive groves, emerald...

A compact archaeological guide to the...

The attention of the global fishing...