Just imagine the scene. It’s the year 1430 and Sultan Murat II has a dream in which God reaches out to him with a rose. The Sultan asks “Can I take it?” God answers “Yes.” This vision emboldens the Sultan. Thessaloniki – with its fortifications, its fertile plains by the Axios River, with the Bay of Thermaikos for a harbor and, just for show, Mount Olympus majestic in the distance – is the rose of his dream. He takes it.

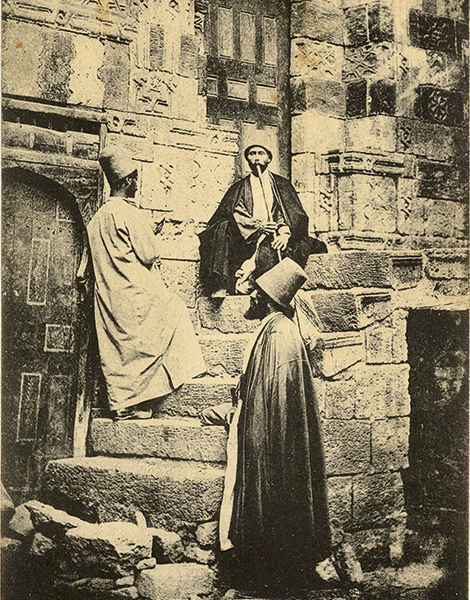

Our tour “Selanik – The Rose of the Sultan” takes us through those centuries (1430-1912) when Thessaloniki was a vital, thriving Ottoman city. You can still taste it in the syrup pastries, the rich creams and the dishes that are zestier and spicier than elsewhere in Greece. You can hear it in the dishes’ exotic names, too. Nothing distinguishes our lively spice markets from those of Istanbul but the language. The Ottoman presence lingers, especially in the upper town with its winding paths and traditional houses with their cantilevering upper stories. Water still flows from public fountains with Arabic inscriptions and, at the edge of a shady square, you may come upon a tourbe (tomb) of a Sufi holy man.

The Romans left stunning monuments – a triumphal arch, an Agora, a Rotunda. Then the Byzantines built a wealth of early Christian churches, and the walls of the upper city – now so picturesque – that ultimately failed to keep the Ottomans out. The Ottoman architectural presence is more subtle.

© Aris Papadopoulos

© Aris Papadopoulos

We start our tour near the city’s sole minaret; travelers of earlier eras write of the city once being aglow with them “like fireflies from a distance.” It is tall and elegant, but dwarfed by the Rotunda it still graces. For Thessaloniki’s urban scale, the Rotunda is massive – 24,5m wide and 29,8m high. It’s easily likened to the slightly older (and larger) Roman Pantheon. Not long after Galerius had it built, the Rotunda became the Church of Aghios Georgios. It stayed a Christian place of worship until 1591, when it was dedicated as the Mosque of Suleyman Hortaji Effendi (acquiring the minaret, the fountain for ritual cleansing outside the entrance, and a plaque in Arabic above the door).

As we enter the building, we’re all caught up in the sight of an unobstructed soaring space and in the glittering mosaics. Then our guide Tassos Papadopoulos passes around a portrait of a celebrity visitor – guesses abound, none of them correct. It turns out to be Herman Melville. Layers of history collapse on each other; the author of Moby Dick came in 1856 and later wrote of standing right here with stones in his trouser pockets, stones that had fallen from these very mosaics. We gaze up at that same ceiling. Thessaloniki has a way of making the past feel very close.

Why would the city have such scarce evidence of nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule? The Ottomans themselves were never in the majority – at times they accounted for only a quarter of the population. Their building needs, never very great to begin with, were largely met by what was already here. The Panaghia Acheiropoietos (“Church of the Virgin Not Made by Human Hands”) became the “Old Friday Mosque,” named for the service of thanksgiving for victory. An inscription on one of the columns – legible still – commemorates the taking of the city by Murad II. This mosque continued to serve as the center of Islamic spiritual life.

“Travelers of earlier eras write of the city being aglow with minarets ‘like fireflies from a distance.’ Today, only one remains.”

Other great churches of Thessaloniki became mosques over the years, while small neighborhood mosques were also built by various benefactors. What remained of these after the Ottomans left was destroyed in the fire of 1917. However, two magnificent 15th-century mosques do remain, and we will be seeing them both.

One is the Aladja Imaret (1484) – a jewel-box hidden by the mid-20th century apartment buildings surrounding it. Even if you came up on it by chance, you might keep walking – the broad porch is unremarkable, and except for the muqarnas above the door, there is little hint to the building’s character. The splendor of the inside takes you entirely by surprise. Two domed chambers – the front one a meeting area, the back one a prayer hall – are filled with intricate niches and arabesques. Much of the original painting is gloriously intact, as are segments of inscriptions on the walls. The name evokes both the look and purpose of the structure. “Aladja” means many-colored and refers to the stones that adorned the minaret that once stood outside, a vestige of an ornate Persian architectural style unusual in this part of the Islamic world. An “Imaret” is a house of charity – the mosque served as school, soup kitchen and prayer hall. Now a space for exhibitions and performances, the mosque has known other uses as well: a man following the tour with us shared his own history of the Imaret – as a boy, he was entrusted with the key to the building, a great heavy thing of iron, he said. He was given the key as head of his boy scout troop. The Imaret was to be their new den, and he recalled unlocking the door for the first time – after perhaps decades of disuse – and finding it much as we see it today, but with fully half a meter of undisturbed dust inside.

We come to a clearing with a fabulous vista – Aristotelous Square and the ruins of the Roman Agora, the shimmering bay and, beyond that, a trace of the white peaks of Mount Olympus. The Church of Aghios Dimitrios, with its shrine to the city’s patron saint, is in a choice location. Sultan Byazid II dedicated it to Islam in 1493, and it became the Kasimiye Mosque. Kasimiye is the Muslim incarnation of St. Dimitrios. His tomb was kept open for both faiths, and Christians continued to worship him here, with rituals performed by the Hodja.

This same neighborhood above the downtown area also has a site from the end of the Ottoman Empire – the boyhood home of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, father of the Republic of Turkey. It is now the Turkish Consulate and a museum, filled with artifacts from his daily life as well as biographical texts and a convincing life-sized wax likeness. The pomegranate tree planted by his father still grows in the walled garden. So many visitors from Turkey come here that a cafe across the street serves tea in delicate little glasses, with sugar cubes on the side, just like in Istanbul.

The Ottomans may have departed long ago, but traces of their daily life linger on. I once met a man who had been to the Bey Hamam (also known as Paradise Baths) for a steam bath when he was a boy – it was open right up until 1968. The baths are just west of “Old Friday,” – which was the city’s main mosque when Murad II built the baths in 1444 as a place for people to prepare for worship. The inside of the baths is closed to the public, but we hear it’s very grand – it was most recently used as the primary location for a period film set in an Algerian bath house. Happily, part of the structure operates as a cafe, with access to the roof. We take a break here for a coffee among the domes of the hamam – a particularly exotic, surreal slice of Thessaloniki.

“What remained of the mosques after the Ottomans left was destroyed in the fire of 1917. Only two remain: the Aladja Imaret and the Hamza Bey Mosque – known as Alkazar.”

Close to the Bey Hamam is the former town hall, which older residents still call Caravan Serai, meaning a hostelry for travelers arranged around an open courtyard for their animals. (Today’s less romantic counterpart is the parking area in the basement.) Directly in front of this building is the Hamza Bey Mosque, the city’s most prominent Islamic building, larger than the Aladja Imaret and right in the city’s center on Egnatia Street, the main commercial street of downtown Thessaloniki. In all likelihood the first mosque built in the city, it started as a simple prayer hall, or Mescid, built in honor of military commander named Hamza Bey by his daughter, Hafsa Hatoun, in 1468. It was augmented over the years, acquiring a large asymmetrical courtyard with a portico of borrowed Byzantine columns supporting graceful pointed arches. The building was in use for years after the Ottomans left – small shops crowded into its exterior spaces. The grand courtyard, covered then, was a cinema (at times an adult cinema) called the Alkazar. In fact, the mosque is still better known today by this new name (just as the Yeni Hamam – The New Baths – is called “Aigli” after its cinema) as is indeed this part of town; the bus stop, too, is “Alkazar”. Today, both the shops and the cinema have gone and the mosque is being restored for yet another role in the life of the city – it will be the most elegant of metro stations.

Across from the Hamza Bey Mosque on Egnatia Street is the “Bezesten,” another prominent Ottoman building that survived the 1917 fire, a grand six-domed market built by Bayazid II, a vizier of Mehmed the Conqueror (Mehmed was the son of Murad II, and was conqueror of Istanbul). The rents from this market were dedicated to the Hamza Bey Mosque, and when the Aghios Dimitrios Church became the Kasimiye Mosque, rents from these shops supported it as well. Today, the building functions much as it always has – Bezesten means fabric market. Just to the east is another market from the Ottoman era – the original structures are gone, but the Kapani (“Flour”) Market is still where dry goods, fresh produce and olives are sold.

A wonderful book by Mark Mazower, titled “Salonica, City of Ghosts,” covers the city’s Ottoman centuries. In it, he quotes the 19th-century writer, diplomat and advocate of the Turkish bath David Urquhart: “Lost to our times and in our portion of the globe.… those habits of ancient days still live and breathe.” Among the olive bins and incense stores of the Kapani Market today, just as in the Bezesten, it seems very little has been lost – in Thessaloniki, habits born during the Ottoman empire are thriving today.

INFO

“Selanik: THE SULTAN’S ROSE”

The tour is conducted regularly by Thessaloniki Walking Tours

• Tel. (+30) 6978.186.900-1