Architectural Icons of Thessaloniki: Eleven Stories Through Time

This short walk takes in eleven...

Mourga

© Nikos Karanikolas

What shaped this city’s food legacy? Much of it was human movement; among those who flocked to its walls were Greek-speaking refugees from Anatolia, Jews from Spain and elsewhere, Pontic Greeks, Palestinians, Syrians, Georgians, Armenians, and internal migrants from Macedonia and Thessaly, all adding their touches to the native cuisine. Then, there’s the city’s geographic position as the maritime outlet for the Balkans, the link between the rest of Europe and Istanbul, and the nearest urban center to the sacred peninsula of Mt Athos.

Thessaloniki has clearly always been a more intriguing melting pot of cultures and influences than Athens. Iakovos Michailidis, professor of Modern and Contemporary History at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki explains that Thessaloniki has been great since its founding. “It is a wealthy city that has condensed and assimilated cultural elements from ancient times, the Roman period, the Byzantine era, the Ottoman Empire, its once vibrant Jewish community, and Asia Minor. It has been one of the most important ports in the wider Eastern Mediterranean region, a gateway to the Balkans and central Europe. Its cosmopolitan character was already evident from as early as the Ottoman period, when caravans passed through the city, transporting goods to and from central Europe.”

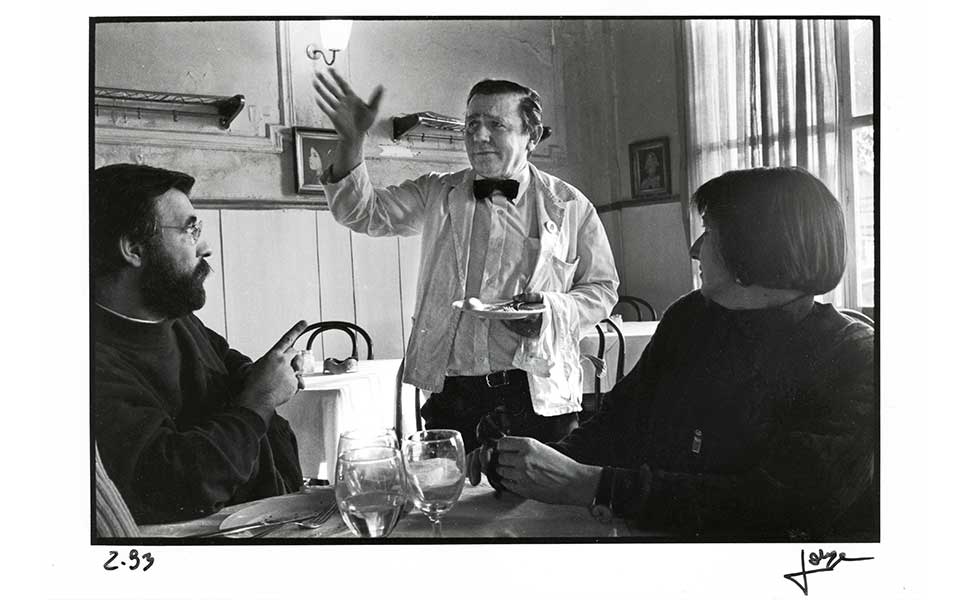

A photo from February 1993, by Roland Laboye, featuring Neoklis, one of the waiters at Olympus Naoussa restaurant, addressing his customers.

© Courtesy of Olympus Naoussa Hotel

Even in times of foreign rule, Thessaloniki was relatively prosperous, and the process of urbanization began there much earlier than other cities in Greece. Due to its strategic location on the Via Egnatia, the road built by the Romans in the 2nd century BC, peoples, armies and goods passed through the city on a regular basis, making it receptive to a wider range of ideas. In the 19th century, it was the seat of dozens of consulates, from the largest to the smallest European powers. During WWI, approximately a million soldiers from many different nations are known to have spent time there: British, Irish, French, Indians, Indo-Chinese, Vietnamese, Moroccan, Canadians, Senegalese, Russians, Australians and New Zealanders, a veritable hub of multiculturalism.

But how is all this related to the city’s gastronomy? From the accounts of soldiers, mainly British troops who fought on the Macedonian front in WWI, we know that they all sought out the food of their home countries during their time in Thessaloniki. The photo book “Thessaloniki: Moments in History,” published by the National Historical Museum (2016), contains images of German prisoners working in the bakery of a French military camp, and of frontline soldiers baking loaves and serving soup. Indeed, there are accounts of how soldiers and officers from all over the world not only cooked for themselves, but also set up eateries and coffee shops in Eleftherias Square and elsewhere in the city. In this, they were like each ethnic group that had passed through Thessaloniki, contributing their own cultural elements and influencing the local cuisine just as others had over the centuries.

The early years of the 20th century were difficult for the city. Prior to WWI, there was the upheaval of 1912, when the city was liberated from Ottoman rule. During the war, there was the great fire of 1917 (a blessing in disguise that resulted in a new urban plan and redevelopment along contemporary European lines). After the global conflict, the ensuing Greco-Turkish War and the Greek defeat of 1922 caused a massive influx of ethnic Greek refugees, earning the city the moniker “Mother of Refugees.” The demographic change was rapid and clearly evident in its cultural footprint. “The city’s darkest periods include the Balkan Wars, when new borders were drawn, and the annihilation of the Jewish community,” Professor Michailidis says. “Thessaloniki endured the scourge of the Holocaust, as well as the terrible trauma of the Civil War, which cut deeper in northern Greece. With the Macedonian Question [a political dispute over which nation would rule the area after the expulsion of the Ottomans] fueling a climate of introversion and insecurity, the city looked inward and closed in on itself. By now, the dominant culture was Greek, characterized to a large extent by elements introduced by [Greek-speaking] refugees from the East.”

Delicious meals are slowly cooked every day in the wood-fired oven at the café Stou Mitsou.

© Christina Georgiadou

Classic local dishes at the taverna Kronos.

© Christina Georgiadou

For many years, the majority of the population lived in poverty. Over time, however, the working class made economic gains. Meanwhile, there were always local elites, mainly merchants and intellectuals. After the collapse of “real socialism” in the early 1990s, communication with the Balkans became more direct and the city took in many Armenians and Pontic Greeks.

This, then, was the identity of the people who lived, cooked and ate in Thessaloniki. But what was their impact on gastronomy? Apart from certain specific recipes that can be identified as “Politikes” (originating from Istanbul), Pontian or Jewish, influences aren’t always easy to discern. Nevertheless, food writer Christos Zouraris, in a recent discussion with Angelos Rentoulas, editor-in-chief of Kathimerini Newspaper᾿s food publications, expressed the interesting view that it was the Anatolian Greeks who introduced a culture of hedonism around food consumption to Greece proper and transformed eating from a daily necessity to a pleasurable ritual.

Writer George Skabardonis remembers that, as a child, he would go swimming with his family at nearby seaside resorts. “From the White Tower we’d take the boat to Peraia and Baxe Tsifliki. I remember my mother carrying a pan of uncooked stuffed vegetables covered with a checkered cloth. Mothers then really cared about food. As soon as we disembarked, she’d take the pan to the nearest bakery where they’d cook the food in their oven, so we could enjoy it hot when we finished swimming.” Who today would go to all that trouble – traveling in a small boat with a big pan of stuffed vegetables – just to eat them fresh from the oven? It seems that pleasure trumped all effort. And they were equally tireless when it came to ensuring there was variety on the table and that everything served was truly delicious. They learned to be inventive, even making use of ingredients considered second-rate, including ground meat from lower-quality cuts and second-grade fish such as thicklip grey mullet. It was the women refugees who introduced many such culinary secrets, having learned them as part of the tradition of their now-lost homelands.

Olympos Naoussa

© Olga Deikou

In the early 1950s, every neighborhood had its own eateries; Toumba was full of ouzo bars and tavernas, as was Kalamaria. There were downtown restaurants, too, establishments long-time residents still remember fondly. “Our table at Olympos Naoussa was reserved specifically for us, and Thanasis, the friendly waiter, always greeted us with a warm smile,” recalls the restaurant critic and food writer Epicurus in his book The Taste of Memory (published by Ikaros). Yiannis Boutaris, winemaker and former mayor of the city, confirms Epicurus’ account. “Unlike other places that were basic eateries, Olympos Naoussa was a restaurant, and a restaurant is all about the staff taking care of the customer. Which is why each waiter had his own customers. [Our waiter] Doxis had ten, and they sat at specific tables.” Middle-class clientele, young bachelors and those who worked in the center and took lunch breaks would eat at these downtown spots. There was Stratis with its stews and casseroles, Athinaikon on Komninon Street, Cairo on Tsimiski, and Elvetiko on Aghias Sofias. Next to the Boutaris family ouzo distillery was the legendary Soutzoukakakia Rogotis. Equally famous was Klimataria, as was ever-packed Tiffany’s, acclaimed for its one-pot dishes. But the real place to be was Krikelas. “We’d go at noon and leave late in the evening; we went there to enjoy it,” says Boutaris, adding with a smile: “What I like about Thessaloniki is its conservatism. Who’s conservative? Someone who doesn’t want change. How nice it was back then, and it really was!”

These and other celebrated restaurants in Thessaloniki had already become well established by the 1980s. Sports bars, such as Café Alpha on the corner of Ethnikis Amynis and Svolou, came into their own, as basketball soared in popularity to rival the affection once reserved only for soccer. City residents and visitors were also living it up at tavernas with live music, including the famed Liolios in the Toumba district and the legendary Dore near the White Tower, and at nightspots known as boîtes, where many now-famous singers began their careers.

The Modiano Market

© Olga Deikou

The Modiano Market, with dozens of ouzo bars and meze eateries, was then in its heyday; boisterous revelries were the norm at The Suspended Step of the Shrimp inside the stoa. “After 1990, most of the good tavernas and restaurants closed, without being replaced by others, so for years the city’s cuisine was indifferent. We were serving pancetta with music; most of the meze bars were very basic and lacking in quality. The restaurants that were expensive didn’t last, while ethnic eateries never took off in Thessaloniki. No ethnic restaurant was embraced by the city for any length of time,” says Giorgos Toulas, journalist and founder of Parallaxi, the first Greek magazine distributed for free.

After 2000, something changed. A culinary guild was set up in Thessaloniki by a group of young professionals who were free of preconceptions and had a shared ideology in favor of collectivity and an interest in everything local and traditional. Young cooks found out what was missing and set about providing it. The city began to acquire small gastro-cafés where diners could enjoy truly delicious food for €20 or less. Yannis Loukakis was involved from the outset in this culinary shift, as were Stelios Emmanouilidis and Dimitris Tasioulas. Many others followed and there was soon quite a buzz about Nea Folia, Sebriko, Pezodromo, Mourga, Maitr & Margarita, Extravaganza, Charoupi (Cretan cuisine), Radikal (sadly no longer open), Nama, Ntangara, Contrabando and, more recently, Iliopetra and Sintrofi.

The people of Thessaloniki were suspicious at first. Over time, however, after eating at some of these new places, they found something of their culinary culture in the food and came to know the riches of their homeland better: cheese products and vegetables from the Macedonian plain, fish and other seafood from Halkidiki, and recipes from Mt Athos. They discovered something new, very tasty and yet – at the end of the day – still familiar, and they accepted it. The same inhabitants of Thessaloniki who aren’t impressed by celebrity chefs, especially if their food lacks substance, made these gastro-tavernas fashionable, and they’re still the envy of Athens today.

Chef and co-owner Giorgos Chlouzas at Nea Folia.

© Olga Deikou

Sintrofi

© Nikos Karanikolas

“There’s pressure on us cooks for the restaurant to measure up. The customers have certain demands. You must do the best you can with simple dishes at a reasonable price: food that’s accessible and affordable, without frills,” says Manolis Papoutsakis, chef at Charoupi and Deka Trapezia. This is why the gastro-cafés succeeded in changing the landscape. The cooks used ingredients that they knew: not Purple Peruvians, but potatoes from Orestiada. They changed the way that traditional sausages, cured meats, Tsouska peppers, offal and Kasseri cheeses were used in cooking, and they prepared many other recipes with readily available ingredients. “Without intending to, the city made fashionable the food that’s now fashionable all over the world,” says Papoutsakis. They also made Thessaloniki a place of great culinary interest today.

In this city where great delicacies were born, where the main square is filled with the aromas of mahlepi and salep, where sesame seeds from bread rings leave crumb trails on the sidewalks, where you can find beef patties stuffed with gyros grilled over charcoal, where Smyrna meatballs have no sauce, where people line up for tripe soup, and where you can find deliciousness and originality in what may appear to be the humblest food (piroshki dough with bougatsa cream filling), the food continues to thrill foreigners and locals alike. Everyone together and each person individually has contributed towards making Thessaloniki a city of pleasure, a place where generosity is the order of the day.

In 2021, Thessaloniki became the first Greek city to join the UNESCO Creative Cities Network in the field of gastronomy.

This short walk takes in eleven...

The Thessaloniki-born winemaker welcomes us to...

Discover how Christos, Athens’ master souvlaki...

Experience Crete’s slow food philosophy where...