Thessaloniki: 6 Creative Locals Offer Their Own Tips

Six creative Thessaloniki locals share their...

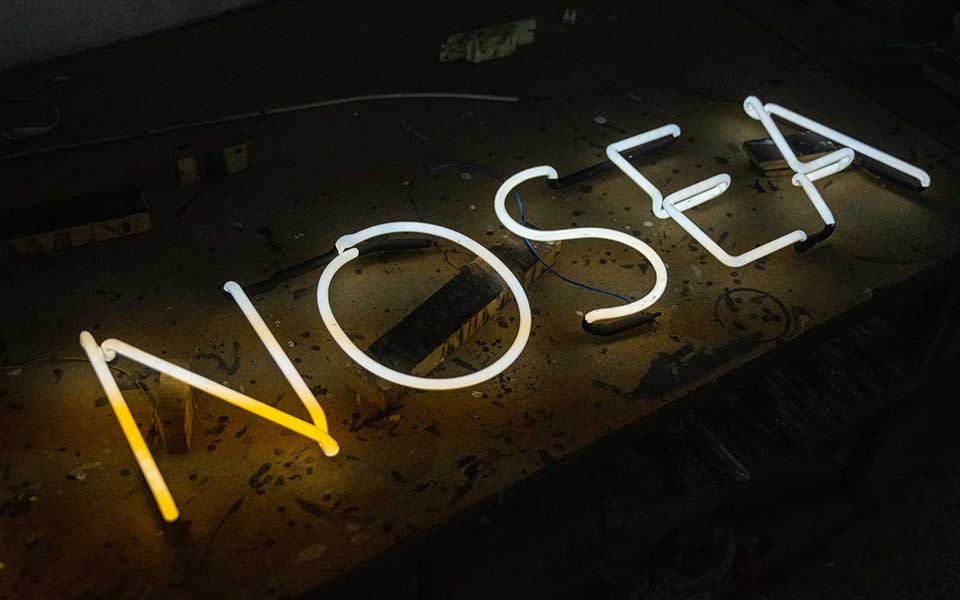

Artist Bill Balaskas working on his most recent neon project, which will feature the phrases: “There Is No Sea Without land” and “There Is No Land Without Sea.”

© Thanos Kartsoglou / Ergon – Culture

Bill Balaskas is a London-based Greek artist, writer and academic whose thought-provoking, evocative and often bitingly humorous mixed-media works impact individuals around the world.

Often, he explores the human soul, social constructs and political as well as economic and commercial phenomena, and technology. Balaskas delves into the past, present and future and never fails to refer to the visual culture of globalization. His works have been exhibited internationally in galleries, museums, festivals and public spaces.

We reconnect after years of pandemic silence to discuss his latest project “2291,” which is being presented in Thessaloniki as part of the “All of Greece, One Culture” initiative by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

“2291” is a new project, produced by Ergon-Culture, which is inspired by the centenary of the Asia Minor Catastrophe (1922) and, in particular, the tragedy of the Burning of Smyrna (Izmir). As the artist reveals here, the work has both an ideological and personal importance to him.

"The aim of the work is to propose a more contemplative, poetic, or – even – optimistic approach to the trauma caused by the Asia Minor Catastrophe, but also to reflect on the timeless and universal nature of refugee crises," Balaskas says.

© Thanos Kartsoglou / Ergon – Culture

What is the main message and impetus behind “2291”?

“The main component of “2291” is a new neon installation that will be displayed in the garden of the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki until September 15 of this year, featuring the phrases: “There Is No Sea Without land” and “There Is No Land Without Sea.” The phrases will be illuminated in alternation every 24 hours, with the change happening at midnight of each day.

The aim of the work is to propose a more contemplative, poetic, or – even – optimistic approach to the trauma caused by the Asia Minor Catastrophe, but also to reflect on the timeless and universal nature of refugee crises.

Thessaloniki is not only the place where I was born and grew up, but also a city whose modern history has been defined by the Asia Minor Catastrophe. Thousands of refugees persecuted by the Ottoman empire arrived in Thessaloniki immediately after the Catastrophe and in the years that followed. This created many challenges for the city, but it also enriched the cosmopolitan character that it had for large parts of its history.

My grandfather, Michael Orphanides, was one of the refugees who left Smyrna in September 1922 to survive the atrocities. He was just 11 years old. The work is based not that much on his memories relating to the pain of the Catastrophe, but rather on how he led his life following it – namely, with hope, dedication, and belief in his personal future, the future of his children, and the future of his country. Hence, the title of the project, which reverses the year of the Catastrophe to invite us to consider the future, and what this might look like.

Also, the location at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki is particularly important for the installation. The museum is situated just outside the Eastern Byzantine Wall of Thessaloniki, which was a key point of departure and arrival for centuries. A few hundred metres south of it, one can find the modern waterfront, close to where the city’s ancient port used to be located.

And the collections of the museum include numerous artefacts that document the birth of extraordinary civilizations and their downfall through both peaceful and violent waves of migration which have often involved long voyages.

Geography, politics, and culture are inextricably bound in this part of the world… So, the garden of the museum is an ideal location for the installation, as thousands of locals, passers-by, tourists, and museum visitors will have the chance to experience it until September 15.

My aspiration is that through the neon installation and all the other components of the project, 2291 will become an imaginary date referring not only to the universality and timelessness of refugee disasters but also to the hope that they will disappear sooner rather than later – hopefully, much earlier than the imaginary year 2291.

Bill Balaskas and Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, "Before the Bullet Hits the Body," 2021, ground mural (vinyl stickers) at Pedion tou Areos park, Athens, Greece. A commission by the Stegi Cultural Centre of the Onassis Foundation.

© Giorgos Papacharalampous, Courtesy of Onassis Stegi

How has your work evolved, changed, and developed over the past few years? Did the pandemic impact your work?

I don’t think that there has been any artist around the world whose work has not been touched either directly or indirectly by the pandemic. For me, the pandemic was an opportunity to focus more systematically on my work in theory and writing. I published two books in two years, in collaboration with Carolina Rito – one in 2020, “Institution as Praxis – New Curatorial Directions for Collaborative Research”; and one in 2021, “Fabricating Publics: The Dissemination of Culture in the Post-Truth Era.”

It was a wonderful opportunity to collaborate with philosophers, artists and curators, whose work I have always found inspirational in different ways – from ruangrupa and Forensic Architecture to Terry Smith; and from Mieke Bal and Joasia Krysa to Steven Madoff.

In terms of new artistic work, I produced two new large-scale installations, both of which were first exhibited in Greece. The first one was in the context of the Primarolia Festival in Aigio, in 2020; and the second one in Pedion tou Areos, in the context of the exhibition “YOU and AI: Through the Algorithmic Lens” by Stegi of the Onassis Foundation, in 2021. Both expanded my work in the area of contemporary socio-political issues by focusing on migration and decolonization.

The neon installation in Thessaloniki touches upon some of those themes, albeit in a more poetic way. However, it also deepens another strand in my practice, which relates to war.

So, returning to your question, the pandemic has been a period of shifts, but also a period of continuity. The vision remains consistent, but the means might change and adapt.

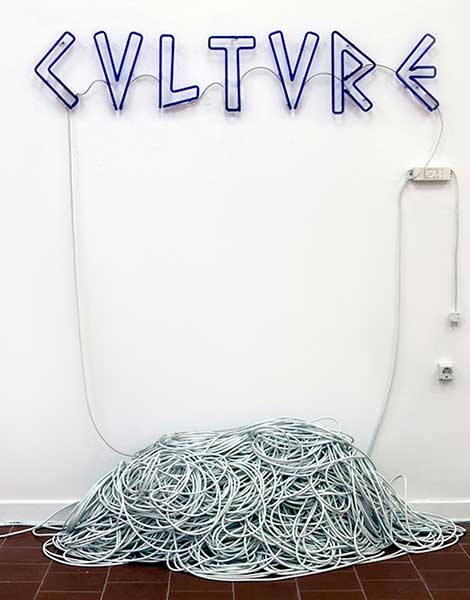

"Culture," 2013, mixed-media installation (neon, 1,000m of cable, socket).

© Bill Balaskas Official

London-based Greek artist, writer and academic Bill Balaskas's newest work, "2291" is dedicated to the centenery of the Smyrna Catastrophe.

© Thanos Kartsoglou / Ergon – Culture

Overall, how would you describe the works you have been producing throughout your career as an artist?

I am using various media and techniques in my works to explore contemporary social and political issues that I consider important. This is an interest that I have held from a very early age, and it is also significantly informed by my original studies in economics, which I have always seen as the first stage in my artistic education.

I am also interested in the connection of such issues with visual culture – the visual language of globalization. In other words, how are such issues presented and perceived, and what can art do to reveal or subvert dominant modes of visual communication?

Usually, it is the content or the subject of each work that leads me to the medium or material that I will use. However, the medium also depends on the location and the kind of interactions that the location is likely to produce for an audience, or for different audiences.

When I am working in a public space with a temporary intervention, like I am doing now in Thessaloniki, I must take into consideration the fact that a highly diverse audience will experience the work. This creates a few challenges, but it also offers some unique opportunities. The use of language – including the choice of using the English language – is a component that, in a way, addresses the challenges and capitalizes on the opportunities.

"Entrapment," 2020, mixed media installation at the Primarolia ships warehouses in Aigio, Greece (64 rodent traps – half open, half closed – following a chess-board pattern; and antique prints depicting children with entrapped rodents.

The key element here is the element of surprise. First of all, the surprise of using a “banal” or “democratic” medium like neon – depending on how one wants to see it – as part of a contemporary art installation presented at the garden of an archaeological museum.

Also, the oxymoron of the phrases themselves creates a surprise, which offers an opportunity for pausing – that is, inviting the passer-by, the visitor to the city or the museum to pause and reflect on the self-evident, or the seemingly self-evident, nature of the two phrases: “There Is No Sea Without land” and “There Is No Land Without Sea.”

Often, the impetus for my artworks is nurturing this element of surprise which may create an opening – an opening to see the world from a different point of view. To question, to decode, to reposition an image, a combination of materials, a word, or a phrase… This is an approach that may be applied to different social and political issues, while also putting forward a process that can, hopefully, encourage a different way of thinking that goes beyond the issues that work is addressing. This is the most inspirational side of my work, not only as an artist but also as a writer and an educator.

Six creative Thessaloniki locals share their...

Igor Borisov turned Kimolos into his...

We asked eight of Thessaloniki’s most...

The West Wall Collective revitalizes Thessaloniki’s...