From Sacrifice to Souvlaki: How the Ancient Greeks...

As Greeks gather for their Tsiknopempti...

View of the Erechtheion, with its southern Porch of the Caryatids. Replicas stand in for the original maidens, who (except for one in London) now reside in the Acropolis Museum

© Shutterstock

There is something missing on the Acropolis these days, something even more important and meaningful than the ancient temples’ bomb-blasted architectural elements and the notoriously plundered sculptures we so frequently find ourselves focusing on.

Among the magnificent white-marble buildings that once adorned the Sacred Rock, thanks to the Athenian statesman Pericles, the Parthenon (447-432 BC) was indeed the most splendid; and within that famous temple was the most extraordinary work of its sculptural collection.

This masterpiece – the most impressive and talked about in the centuries after the Golden Age of Classical Athens – was the gigantic, chryselephantine cult statue of Athena Parthenos, a massive gold-and-ivory jewel of ancient Greek art, now lost in the mists of time.

An artist's impression of the gold and ivory statue of Athena Parthenos

© Acropolis Museum

Thematic tour

This central feature of the Parthenon may be long gone, but shadows of it remain in the form of historical accounts, faint archaeological traces and various artistic tributes widely produced in “late Classical, Hellenistic and Roman reliefs, statues, medallions, intaglios, tokens, gems and coins” (J. Hurwit).

And now, drawing on such material, the Acropolis Museum has organized a new thematic tour for its visitors to better know and celebrate this wonder of the ancient world.

Until the end of December, a special program, “The Lost Statue of Athena Parthenos,” led by an archaeologist-host, gives visitors a chance to view an amazing video presentation featuring a 3D computer reconstruction of Athena’s greatest statue, as it was originally seen inside the Parthenon.

Afterwards, participants move to the museum’s third-floor gallery for discussions of the Parthenon’s metopes, with their dynamic images of the Gigantomachy, Centauromachy and Amazonomachy. Particular topics during the talks include the statue’s materials and construction techniques, its patriotic symbolism for ancient Athenians and the public scandals that swirled around it, instigated by Pericles’ relentless political rivals.

To: December 28, 2019

The Acropolis Museum invites its visitors on a walk of knowledge about its construction materials and techniques, its myths and allegories, its radiance and its adventures.

English: Every Saturday at 11 a.m.

Greek: Every Saturday at 1 p.m.

Duration: 50 minutes

Price: Only the general admission fee (€5) to the Museum is required.

For more information click here.

The Erectheion, which stands on the Acropolis, was once the headquarters of the priestess of Athena

© Shutterstock

Key to a complex temple

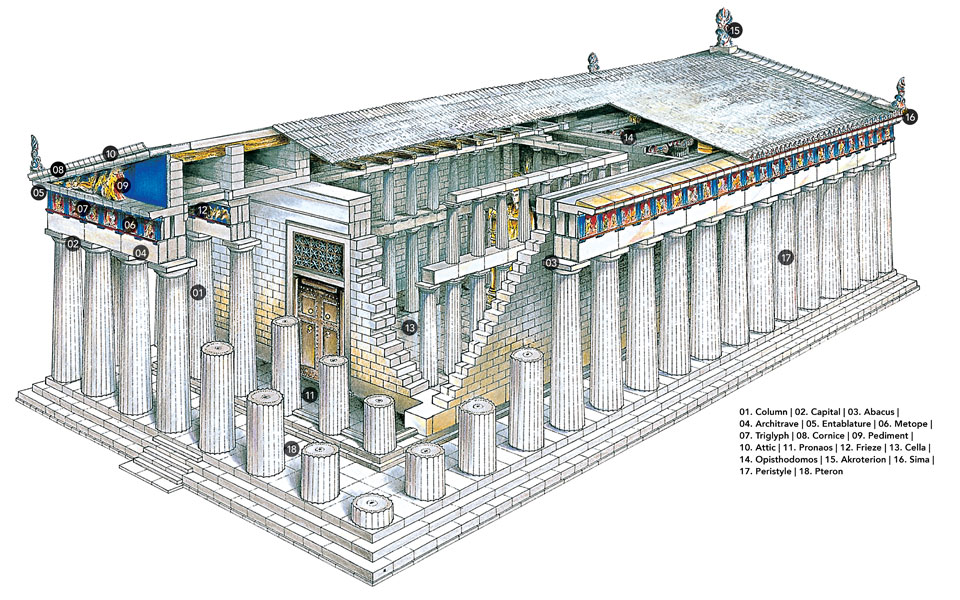

Although the Parthenon was a temple, and basically served, like other temples, as a protective shelter for a cult statue, it was not the focus for the regular worship and rituals associated with the deity it housed. Inside its cella (inner sanctum) stood Athena: the city-state’s divine patroness and namesake; the warrior goddess who led Athenians in their military victories.

Yet Athena’s primary cult statue, an age-old figure carved from olive wood, was kept in the adjacent temple, the Erechtheion, which replaced a succession of earlier temples of Athena in this central area of the Acropolis. The priestess of Athena was headquartered at the Erechtheion; the altar used for sacrifices to the goddess stood near its east end.

So, what was the Parthenon?

A simple answer cannot be given, as it served many purposes.

It was foremost a gift to the gods, particularly Athena, in gratitude for her patronage and granting of Athenian triumphs on the battlefield – especially over the Persians, who had recently invaded Greece, Athens and even the Acropolis in 480/79 BC.

The Parthenon was also a giant message board, whose sculpted metopes on its four facades held allegorical scenes of mythical battles known to all Greeks – the Gigantomachy, Centauromachy, Amazonomachy and Trojan War – legendary tales which celebrated the Greeks’ ability to render civilized order from wild nature and chaos.

At the same time, Pericles appears to have meant for the building to be a tribute particularly to Athenian greatness and the city’s progressive democratic reforms.

The Parthenon’s eastern pediment tells the story of the birth of Athena, framed by the rising and sinking chariots of Helios (Sun) and Selene (Moon) – a special day in the life of the world.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Most intriguing, the Parthenon is now coming to be viewed by many scholars as a monument not only to the goddess Athena, as we see from her birth myth depicted on the east pediment, but also to Athens’ mythical foundation – evoked first (to the ascending visitor) in the west pedimental sculpture showing the contest for dominance between Athena and Poseidon.

Further allusion to the city’s birth, classicist Joan Connelly has argued since the 1990s, is found in sculpted depictions of the legendary king Erechtheus and his family, especially his daughters, represented in the frieze’s emblematic central scene located directly over the Parthenon’s eastern entrance.

The much-admired, oracle-decreed self-sacrifice of these three virgins (“parthenoi”), known as the Erechtheidai, on behalf of their city-state – prior to a legendary war between Athens and Eleusis (whose king was Eumolpos, son of Poseidon) – consequently allowed Athens to triumph over Eleusis, remain independent and go on to become the great, leading city of Classical Greece.

Inside the temple, the Parthenon’s splendid cult statue was the culminating embodiment of all these functions and sculpturally evoked meanings of the monument – a key to understanding, both then and now, which brought together through its own form and decorative elements all the mythical themes displayed throughout the building.

The statue

The statue of Athena Parthenos was created in 447-438 BC by the master sculptor Pheidias – very likely in an on-site workshop now also gone, but similar to the one we still see at ancient Olympia, where he also created that sanctuary’s cult statue of Zeus (435 BC).

Unlike Olympia’s seated Zeus, Athena Parthenos was standing, nearly 12 m tall, her exposed flesh rendered from pale ivory, her armor and “peplos” robe from gleaming gold, weighing a total of at least 40 talents, about one metric ton.

The sculpture was hollow, formed of a wooden armature covered with removable plates – which proved fortuitous, Plutarch reports (Pericles 31.2-3), when Pheidias was later accused of embezzlement, but absolved of guilt when he was able to disassemble the individual gold plates and have them weighed.

Athena’s extended right hand supported a golden Nike statue, about 2 m tall, while her left rested on top of her shield beside her.

Mythological images appeared everywhere on Athena’s statue: her helmet bore a sphinx, winged horses (Pegasoi), griffins and deer; her gold breastplate/aegis featured a central ivory portrait of the Gorgon Medusa; her shield (almost 5 m in diameter) displayed the Amazonomachy on its outer surface, the Gigantomachy inside; and the edges of her sandals were decorated with the Centauromachy.

Coiled beside Athena was a golden snake, the sacred protector of the Acropolis. Additionally, as the Roman-era traveler Pausanias (1.24.7) tells us, this serpent was the incarnation of indigenous, earth-born Erechtheus/Erichthonios, the “son” of Athena and Hephaistos and the grandfather of mythical King Erechtheus, the primordial ruler (after Kekrops) of Athens.

The cult statue’s white, Pentelic-marble base (about 90 cm tall) is particularly significant for Athenian mythology and our understanding of the Parthenon’s sculptural iconography.

Across its façade, visible to all visitors, was a series of gilded bronze figures. At the center stood a young woman, about to be crowned by an older female on her left. Pausanias identifies the central figure as Pandora, the first woman, as described by Hesiod. However, due to a confusion that had arisen over the centuries since the Parthenon’s creation, or to the traveler’s own misunderstanding of his local guide, Pausanias, it appears, was mistaken.

A statue of Athena outside the Academy of Athens.

© Shutterstock

Which Pandora?

The maiden shown on the base supporting Athena Parthenos was very likely not Hesiod’s Pandora, as she had no relevance to Athenian mythology or tradition. Instead, she was Chthonia, Erechtheus’ youngest daughter – a figure of great import for Athens – who Connelly has convincingly argued from iconographic evidence may also have been called “Anesidora” (she who sends up gifts) and/or the related “Pandora” (giver of all).

Euripides, in his tragic play Erechtheus (about 422 BC), simply calls this daughter “Parthenos,” the virgin. The female figure to her left is Athena, flanked by Hephaistos – her two ancestral “grandparents.” The goddess (perhaps representing the city of Athens itself, as she did so often in ancient art) honors the girl with a crown, an act of Athenian tribute Euripides has her mother Praxithea predict in a dramatic speech.

The great local significance of Erechtheus and his daughters is confirmed in Roman times by Cicero (Nat. D. 3.50), who writes these mythical figures “have been deified at Athens.” Pausanias (1.27.4), too, during his Acropolis tour, observes, “by the temple of Athena,” two bronze statues of Erechtheus and Eumolpos that are “facing each other for a fight.”

Clearly, the city’s foundation, involving a war between Athens and Eleusis, was a major theme commemorated on the Acropolis.

The Parthenon from above

© Shutterstock

Temple of the virgins

The cult Statue of Athena, then, served to tie together all the Parthenon’s mythical themes and sculpted imagery, including allusions to Erechtheus and the Erechtheidai in the temple’s Ionic frieze.

Although the frieze has long been interpreted as portraying a contemporary 5th-century-BC celebration of the Panathenaia procession, the chronological and other inconsistencies inherent to this long-embraced (since 1787) reading are so numerous as to finally invite its retirement.

It seems that the frieze – as perhaps we should already have begun to conclude following Chrysoula Kardaras’ suggestion in the early 1960s – instead depicts the first, mythical Panathenaia, decreed by Athena to honor Erechtheus and his daughters.

One telling clue is found in the frieze’s chariots, a pre-Classical feature of war no longer employed in Periclean times, nor known to have been paraded in Classical Panathenaic processions.

The frieze’s eastern central scene further highlights Erechtheus, as it shows him with Praxithea and their daughters. The Erechtheidai are about to dress themselves in burial shrouds for their self-sacrifice on behalf of Athens, with Pandora going first – much as Iphigeneia submitted to being sacrificed by her father Agamemnon to allow the Greek fleet to reach Troy.

Framing the central scene, the Olympian gods turn their backs to the daughters’ imminent death, as for them to observe such a mortal sacrifice would be improper and pollute their divinity. The 30+ women that also conspicuously dominate the frieze’s main east side, Connelly recently concluded (2014), are the “sacred maiden choruses that Athena instructs Praxithea to establish in memory of her deceased daughters” — as Euripides later dramatized the myth, apparently inspired by the images carved on the Parthenon.

At the temple’s opposite end, its western chamber (opisthodomos) became a shrine to the deceased “parthenoi” – as this room’s Ancient Greek name “parthenon” (“of the parthenoi”) implies.

If indeed the scene carved on the base of Athena’s cult statue showcased the local heroine Pandora, then the epithet “Athena Parthenos,” according to Connelly, may actually have represented a conjoined epithet or cult – Athena-Parthenos, like that of Poseidon-Erechtheus in the Erechtheion – which reflected the Athenians’ great reverence not only for the virgin goddess Athena, but also for the youngest, virgin daughter of Erechtheus.

To: December 28, 2019

Τhe Acropolis Museum brings to life the statue of Athena Parthenos, made of gold and ivory, designed by Pheidias for the Parthenon. The museum invites its visitors on a walk of knowledge about its construction materials and techniques, its myths and allegories, its radiance and its adventures.

English: Every Saturday at 11 a.m.

Greek: Every Saturday at 1 p.m.

Duration: 50 minutes

Participation: For registration, refer to the Information Desk at the Museum entrance on the same day, half an hour before the presentation start time. Limited to 30 visitors per session. First-in first-served.

Price: Only the general admission fee (€5) to the Museum is required. For more information click here.

As Greeks gather for their Tsiknopempti...

In 30 BC, Octavian, the future...

Discover the lesser-known oracles of ancient...

Discover five of Athens’ latest openings,...