Despite the travel bans and safety measures, archaeology in Greece had a bumper year in 2020, unearthing an array of fascinating finds across the country.

Even as the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic reduced overseas tourism last year to a gentle trickle, many archaeological sites across Greece still had daily visitors.

Archaeological teams pressed on with skeleton crews, scaling back their efforts but nevertheless making a startling array of exciting discoveries.

In some cases, the lack of visitors proved a blessing, allowing researchers to pore over popular sites that would otherwise feature crowds of tourists. Meanwhile construction projects in Athens also carried on, leading to a number of unexpected finds.

This list, by no means exhaustive, explores ten of the most significant archaeological finds reported over the past months when Covid’s spread across the globe drew our attention elsewhere.

© Shutterstock

1. Theopetra Cave, Thessaly

New evidence shows Stone Age Greeks ate healthier than many modern humans

Theopetra Cave in Thessaly, central Greece, is a hugely important site that was continually occupied by humans for a staggering 130,000 years. Famous for the fossilized footprints of a group of young Neanderthals and one of the oldest known human constructions – a 23,000 year-old wall – excavations at Theopetra have also revealed the well-preserved remains of a young woman, aptly named Avgi (‘Dawn’) who lived in the cave around 7000 BC, during the Mesolithic period.

Reporting in 2020, prehistoric archaeologist Dr Nina Kyparissi-Apostolika, who led excavations at the cave from 1987 to 2007, presented results from an analysis of recent finds, which revealed further clues about the lifestyle and diet of the cave’s later Neolithic inhabitants.

A study of the bones of 43 people who lived in the cave during this period show that they were quite a healthy group, subsisting on a diet of wheat, barley, olives and pulses – staples of the traditional Mediterranean diet that we all know today. A moderate amount of meat from a mix of domesticated and wild animals was also consumed, including wild boar – a big game species that still roams the Greek countryside.

It was also found that domesticated sheep and goats represented around 60 percent of the animal bones at the site, and were likely kept for their by-products of wool and milk in addition to their meat. Further evidence suggests the cave’s inhabitants also kept cattle, pigs, and at least one dog, perhaps as a companion for hunting and herding.

© Vangelis Zavos

2. Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera)

Spectacular new finds uncovered in “Greece’s Pompeii”

Santorini’s strategic position on the maritime routes between the southern Cyclades, Crete, and the copper-rich island of Cyprus ensured it became an important center for trade in the Middle Bronze Age (or Middle Minoan, 2160–1600 BC).

In early 2020, Professor Christos Doumas reported on recent archaeological finds made during excavations at the famous settlement of Akrotiri in the south of the island.

Among the finds in the interior of a building known as the ‘House of Thrania’ (‘House of Benches’) – most likely a public or communal building – were two large double-headed axes (Diplous pelekys or labryes) made of finely-crafted bronze plates; these are artifacts that are emblematic of Minoan culture and religion in Crete and the southern Aegean.

Also found were a large number of miniature ceramic vessels, perhaps used as drinking cups during group rituals, other bronze items, and fragments of jewelry, including a small bead of rock crystal carved in the shape of a figure-of-eight shield.

Most remarkably, the team discovered an inscription of Linear A, an as-yet undeciphered writing system used by the Minoans, on a fragment of what would have been a wooden construction, perhaps a box or chest. These finds shed more light on the life of the inhabitants of the Bronze Age town prior to the Theran eruption in 1628 BC, one of the largest and most catastrophic volcanic eruptions in the history of the Mediterranean.

Since the first excavations started in 1967, the site, often referred to as the ‘Minoan Pompeii’, has revealed thousands of beautifully preserved artifacts, many of which are on display in the Museum of Prehistoric Thera. Eye-catching frescoes and entire pieces of wooden furniture, preserved for three-and-a-half millennia in the volcanic ash, present some of the most iconic images of Bronze Age Aegean art and culture.

© Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades

© Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades

3. Despotiko, Cyclades

New buildings discovered at the Sanctuary of Apollo on the “other Delos”

2020’s scaled-down excavations on the uninhabited island of Despotiko in the central Cyclades, under the watchful direction of Dr Yiannos Kouragios, uncovered the remains of yet more buildings at the sanctuary, famous for its impressive Late Archaic temple from the 7th century BC.

Two new buildings were found at the sanctuary itself, bringing the total number of structures to 29, while a further eight were found on the nearby islet of Tsimidiri, once connected to Despotiko in antiquity by a narrow isthmus, bringing the total number there to ten. All are large structures with solidly-built foundations, and form part of a vast religious complex dedicated to the god Apollo, mentioned by ancient writers Pliny the Elder and Strabo.

More ceramic artifacts were found on Tsmidiri, including large quantities of decorated storage containers (pithoi), prompting Kouragios to believe the buildings there functioned as warehouses at the entrance of the port.

Much of the attention of this past season, however, focused on the restoration works of the temple, including its decorative pediment, and the large ceremonial feasting hall (hestiatorion). After 22 years of excavations, the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades is now preparing to accept visitors in the not-too-distant future, establishing an open-air museum in the same vein as the site on nearby Delos; another must-see for visitors to the Cyclades.

© Shutterstock

4. Epidaurus, Peloponnese

The mysterious Tholos at the Sanctuary of Asclepius reveals deeper secrets

The ancient theater at Epidaurus in the eastern Peloponnese is a major draw for thousands of visitors every summer, but the theater is only one part of a vast complex of monuments that form the Sanctuary of Asclepius, god of healing, truth, and prophecy.

Capitalizing on the reduced number of visitors, excavations in July 2020, under the direction of Professor Emeritus Vassilis Lambrinoudakis, unearthed the remains of a building underneath the 4th century BC Tholos, the mysterious circular building next to the Temple of Asclepius noted for its subterranean maze.

The hitherto unknown building, dating to the 6th century BC, is rectangular in plan, complete with a pebble mosaic floor and a peristyle (or colonnade) of wooden columns. Traces of a staircase leading up from the basement were also found.

Lambrinoudakis and his team now believe that the cult of Asclepius, where supplicants would come from across the ancient world to be healed of their illnesses, began much earlier at the sanctuary than initially thought, soon after the end of the 7th century BC. Over time, the older building was demolished to make way for the Tholos, which served as Asclepius’ tomb, famously described by the 2nd century AD traveler Pausanias.

© Greek Ministry of Culture

5. Tanea, Corinth

Newly discovered inscription lends weight to an ancient legend about this once-powerful city

Excavations at ancient Tanea enjoyed another bumper season in 2020, with further finds in the areas of the large bath complex and commercial district. Work around the modern village of Chiliomondi, some 15 km southeast of Corinth, started in 2013 under the direction of archaeologist Dr Elena Korka, but scattered artifacts, including the famous Archaic Kouros of Tenea, now in the Glyptothek in Munich, Germany, have been found in the area since at least the mid-19th century.

The legendary city was said to have been founded by Trojan prisoners of war from the island of Tenedos in the northeast Aegean who were brought back to Greece by Agamemnon, and is mentioned in many Greek myths, including the story of Oedipus.

Proof of its existence finally came in 2018 following the discovery of the remains of a housing settlement with carefully-constructed walls, marble floors, and a significant number of richly adorned graves with coins, vases, and jewelry dating to the Archaic and later Hellenistic periods.

Work over the past summer uncovered two inscriptions, one on a statue base from the 4th century BC bearing the name Peisandridas, who ancient writer Pindar describes as the ancestor of the Peisandrids, the hegemonic family of Tenedos. This is the first hard evidence uncovered of a direct connection between the city of Tanea in the Peloponnese and the island of Tenedos, lending weight to the ancient descriptions of its founding by captive Trojans.

Two small coin hoards were also discovered in the baths, dating to the 4th and 5th centuries AD; a further indication of the long settlement history of the city from the Archaic to the early Byzantine period.

© Perikles Merakos

6. Rineia, Cyclades

Mapping the mysterious Cycladic island of Rineia, Delos’ “twin sister”

In this age of pandemic and quarantine, recent work on the island of Rineia has a particular resonance. Used as a quarantine site during periodic outbreaks of plague and cholera until the late 19th and early 20th centuries – Alexandrian Greek poet Constantine Cavafy spent two days there on his first trip to Greece in 1901 – in antiquity, the island served as both a birthplace and necropolis for the nearby sacred isle of Delos, the site of the Sanctuary of Apollo.

With Rineia fabled as the birthplace of Apollo’s twin sister, Artemis, archaeological research on the island began over 120 years ago in 1898, and focused on recording the visible surface remains of numerous burial structures and marble figures, including the famous sarcophagus of the Roman Tertia Oraria and the Great Lion sculpture.

Last summer’s investigations under the direction of the Cyclades Ephorate of Antiquities involved an intensive surface survey that revealed a raft of new and important finds, among them large fragments of sculptures, the architectural remains of ancient farmhouses, a previously unknown road, and the probable location of a temple. Researchers also found remains of more modern structures, including Byzantine and post-Byzantine farmhouses and chapels.

The island is famously mentioned in Thucydides’ Book Three, where he describes the Athenians conducting a ‘ritual cleansing’ of Delos in the winter of 426/5 BC by “exhuming all the dead and their coffins” and transporting them to nearby Rineia, declaring that “no one should die nor be born [on Delos], but the dying and the women about to give birth should be transported to Rineia.”

© Greek Ministry of Culture

7. Aiolou Street, Athens

Ancient bust of Hermes unearthed from beneath a busy downtown Athens thoroughfare

The well-preserved head of a statue depicting the god Hermes was discovered last November during construction works on fashionable Aiolou Street in central Athens, lying a mere 1.3 m under street level.

The head is thought to have formed part of a Hermaic stelai or herma (literally ‘heap of stones’), one of many similar statues that functioned as road markers or indicators of important public or private spaces in ancient Athens. Worshipers also placed these cult statues, often with a squared lower section and male genitalia, at crossroads in the hope of invoking Hermes’ protection on their travels.

This particular example was used as common building material, found built into a wall to support a modern water pipe; a humiliating end for the once-sacred sculpture and reminiscent of the infamous “mutilation of the herms” in the spring of 415 BC. That sacrilegious act, carried out prior to the departure of the Athenian fleet on the doomed Sicilian Expedition during the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), may have been the work of saboteurs, perhaps even Spartan sympathizers from Athens itself.

Based on its style, the newly found bust dates to around the end of the 4th or the beginning of the 3rd century BC and resembles the type of bearded Hermes Propylaios famously sculpted by Alcamenes, considered by many as one of the finest sculptors in ancient Greece. Its unearthing is yet another timely reminder that Athens is still packed with hidden archaeological treasures waiting to be discovered.

© Greek Minstry of Culture

8. Piraeus, Athens

Ancient aqueduct uncovered during Athens Metro works

Large-scale excavations during the ongoing construction works to extend the Athens Metro line to Piraeus have uncovered the remains of an ancient aqueduct and a treasure trove of rare artifacts from Hellenistic and Roman times.

Investigation of the remains of the aqueduct are providing important clues to the city’s water supply system, which brought water to Piraeus from Ardittos Hill along the Long Walls that protected the road linking the city and its port. The sections of the aqueduct under current investigation were in use from the 2nd to 5th centuries AD, from the time of the emperor Hadrian to the Gothic invasions.

The construction works have also led to the discovery of a beautiful pebble stone mosaic floor and a number of ancient wells containing some 4,000 well-preserved artifacts found buried in soft muddy deposits below the water table. Among them are 1,300 rare wooden objects, including everyday household items, furniture, utensils and tools, forming the largest collection of wooden artifacts from the classical world yet discovered in Greece.

One of the rarest finds was a headless wooden statue of the god Hermes, dated to the Hellenistic period, perhaps discarded in a well during the sacking of Athens by the Roman general Sulla in 86 BC. These excavations, under the direction of Giorgos Peppas, demonstrate how large-scale construction works and delicate archaeological research can work hand-in-hand.

Last year, the artifacts were moved to a Piraeus workshop where the archaeological team continue to work to identify, record, and conserve them for a planned exhibition at the Piraeus Municipal Theater metro station. Visitors can watch the archaeologists at work from overhead lofts.

© F. Kvalo / Institute of Historical Research • National Hellenic Research Foundation

9. Kasos, Dodecanese

Roman-era shipwreck provides insight into ancient maritime trade routes

The world of underwater archaeology never fails to fascinate and excite the popular imagination, and the seas around Greece are home to some of the most astonishing finds in the history of the discipline. Preeminent among these is the Roman-era Antikythera wreck dating from the 1st century BC, renown for its cargo of bronze and marble statues, and the remains of a mechanism that many regard as the oldest known analogue computer.

The underwater excavation of yet another Roman-era wreck, this time off the island of Kasos in the southern Aegean and dating to the 2nd or 3rd century AD, has revealed a large cargo of storage jars (amphorae), mainly of types manufactured in Guadalquivir in Spain and in Tunisia. Kasos, the southernmost island in the Aegean, lies at the navigational crossroads between Crete and the Dodecanese, and expedition co-leader Xanthis Argyris believes the vessels contained olive oil, wine, and possibly much-prized fish sauce (garum) destined for the island of Rhodes and ports along the coasts of Asia Minor.

This latest expedition forms part of a three-year research project (2019–2021) aimed at exploring the seabed off Kasos. Under the auspices of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities in collaboration with the Institute of Historical Research of the National Hellenic Research Foundation, a team of 23 specialists conducted around 100 dives in September and October last year, totaling more than 200 hours under water. It is hoped that research will continue in the area this year, including a comprehensive survey using state-of-the-art remote sensing equipment to pinpoint the locations of other sites of interest.

So far, the team have discovered five historical wreck sites, including two from the 4th and 1st centuries BC, a third from the Byzantine era, which included five conical-shaped stone anchors and an iron canon, and a fourth dating to the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s.

10. Thasos, Northern Aegean

An early Byzantine skull on the island of Thasos shows signs of complex surgery

A recent analysis of human remains found on the island of Thasos in the northern Aegean has called into question the way anthropologists understand the development of complex surgical interventions in the early Byzantine period. A total of ten skeletons were exhumed from an early Christian burial ground in the area of Paliokastro, comprising four women and six men, all bearing clear signs of extensive physical trauma.

Researchers believe the individuals, who lived sometime between the 4th and 7th centuries AD, were of high social status on account of the location and architecture of their burial site. Lead researcher Dr Anagnostis Agelarakis believes the men were either horse archers (equites sagitarii) or heavy cavalrymen (cataphractii), elite units of the Late Roman army, and the women were related, possibly as wives. All bear the signs of acute trauma and were treated surgically or orthopedically by an experienced physician.

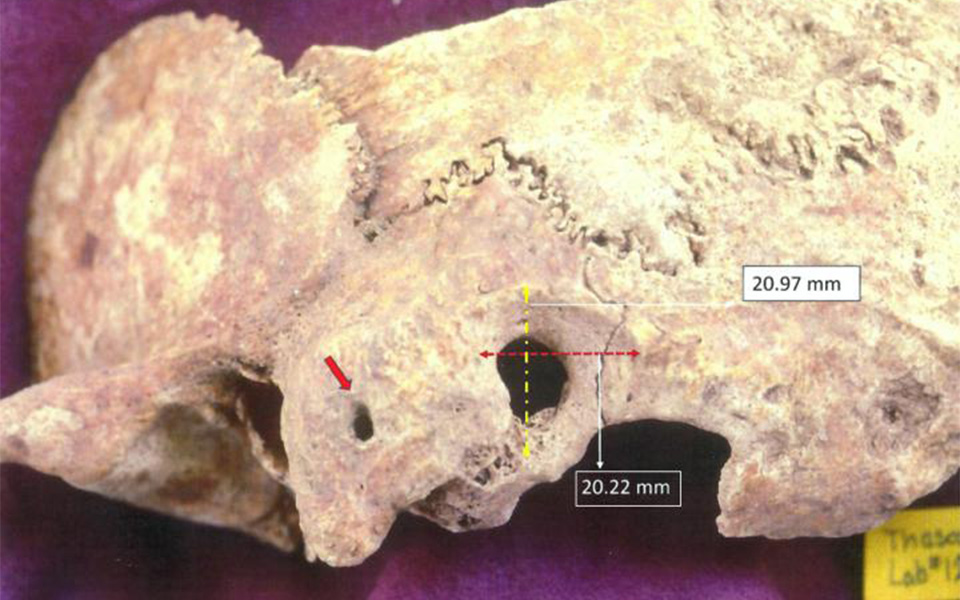

One of the male skulls in particular caught the attention of the team, bearing the conspicuous signs of a delicate and highly dangerous surgical procedure known as trephination (from the Greek trypanon, literally ‘borer’). This procedure involved drilling two tiny holes into the cranium, most likely in an attempt to relieve pressure on the brain due to an infection or the build-up of blood following a severe head injury.

While the archaeological evidence for trephination can be traced back as early as the Neolithic period some 7,000 years ago, the new findings in Thasos suggest an altogether more sophisticated surgical procedure – an early precursor to brain surgery. Furthermore, the mere fact that such a dangerous surgical intervention was attempted in the pre-antibiotic age is evidence that the individual was considered highly important to the local community.

Close inspection of the cranium suggests the man did not survive the surgery, or died shortly thereafter. Nevertheless, it is clear that the procedure was the work of a highly skilled physician, perhaps a military surgeon with extensive experience of treating cases of battlefield trauma.