Ask anyone, anywhere in the world, about Athens and you’re likely to hear back about the Parthenon, the Acropolis, classical antiquity or the cradle of democracy. which is exactly why Barack Obama picked Athens as the location of his 2016 final foreign tour keynote address aimed at defending democracy. It’s also why most visitors used to treat Athens as merely a short stopover on their way to the islands. Athens wasn’t worth much beyond the Acropolis and a couple of museums, or so the thinking went.

Unlike foreign visitors to the city who worshiped it, most Athenians ignored the Acropolis until recently. They did so in spite, or perhaps because of its towering presence over the city’s landscape. After all, omnipresence can feel a lot like absence. They didn’t think much of the rest of their hometown, either. In most part the children and grandchildren of internal migrants who’d settled in Athens to escape the endemic poverty of their ancestral villages during the 1950s and 1960s, the city’s residents saw it as an unwelcoming, impersonal, overpopulated, traffic-clogged, dirty and ugly metropolis, colloquially known as Tsimentoupoli, or “Cement City,” a reference to the ocean of concrete apartment blocks that cover the landscape. For a long time, in other words, Athens wasn’t much loved.

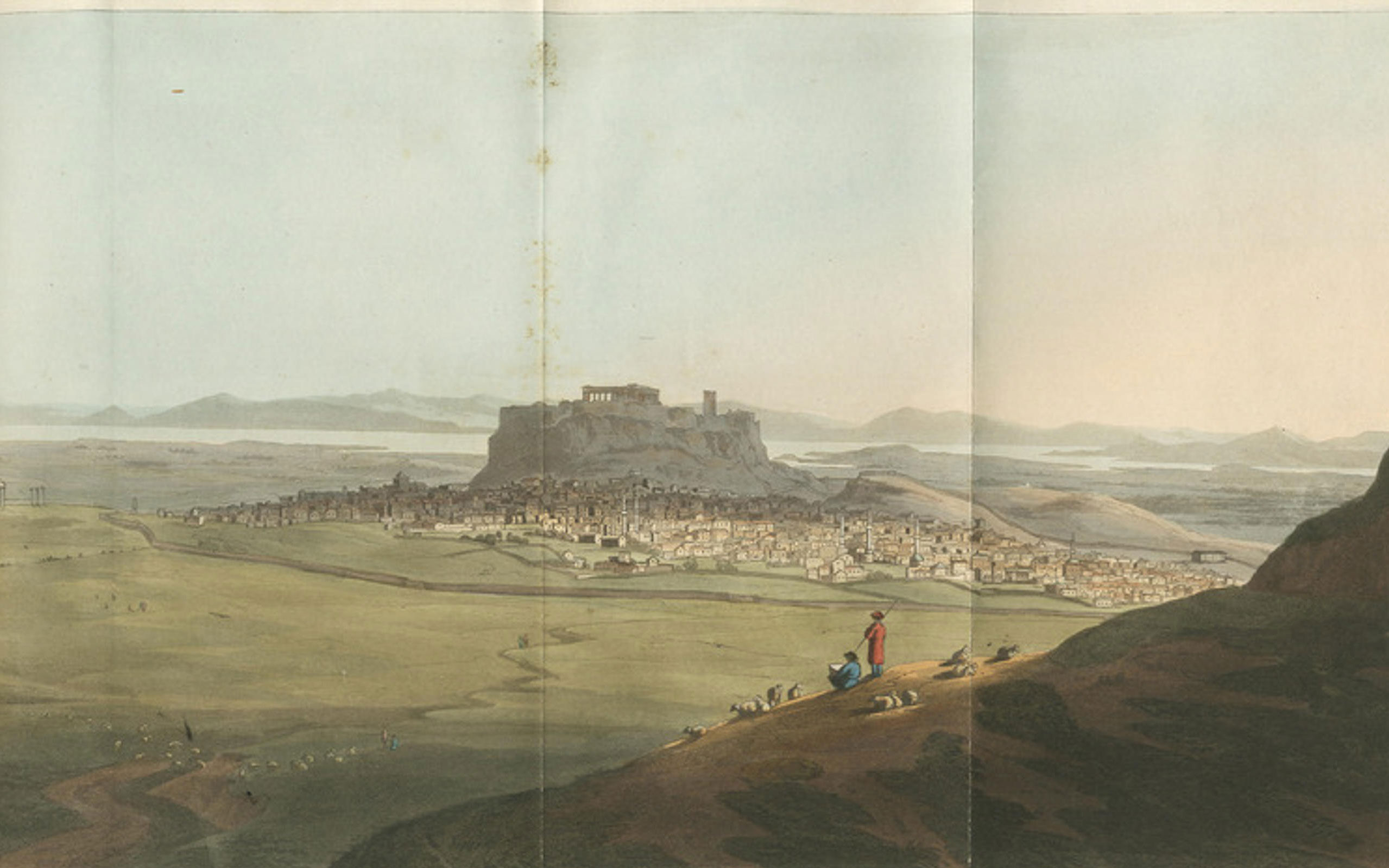

© JOHN CAM HOBHOUSE/VISUALHELLAS.GR

Attitudes, however, change quickly. Visitors stay longer in Athens these days, and some even spend all their time here. Athenians have begun to rediscover and appreciate their city, too. There’s now a growing sense that there’s much more to it than simply a perplexing blend of famous ancient monuments and lots of concrete. How can we explain this surprising turnaround?

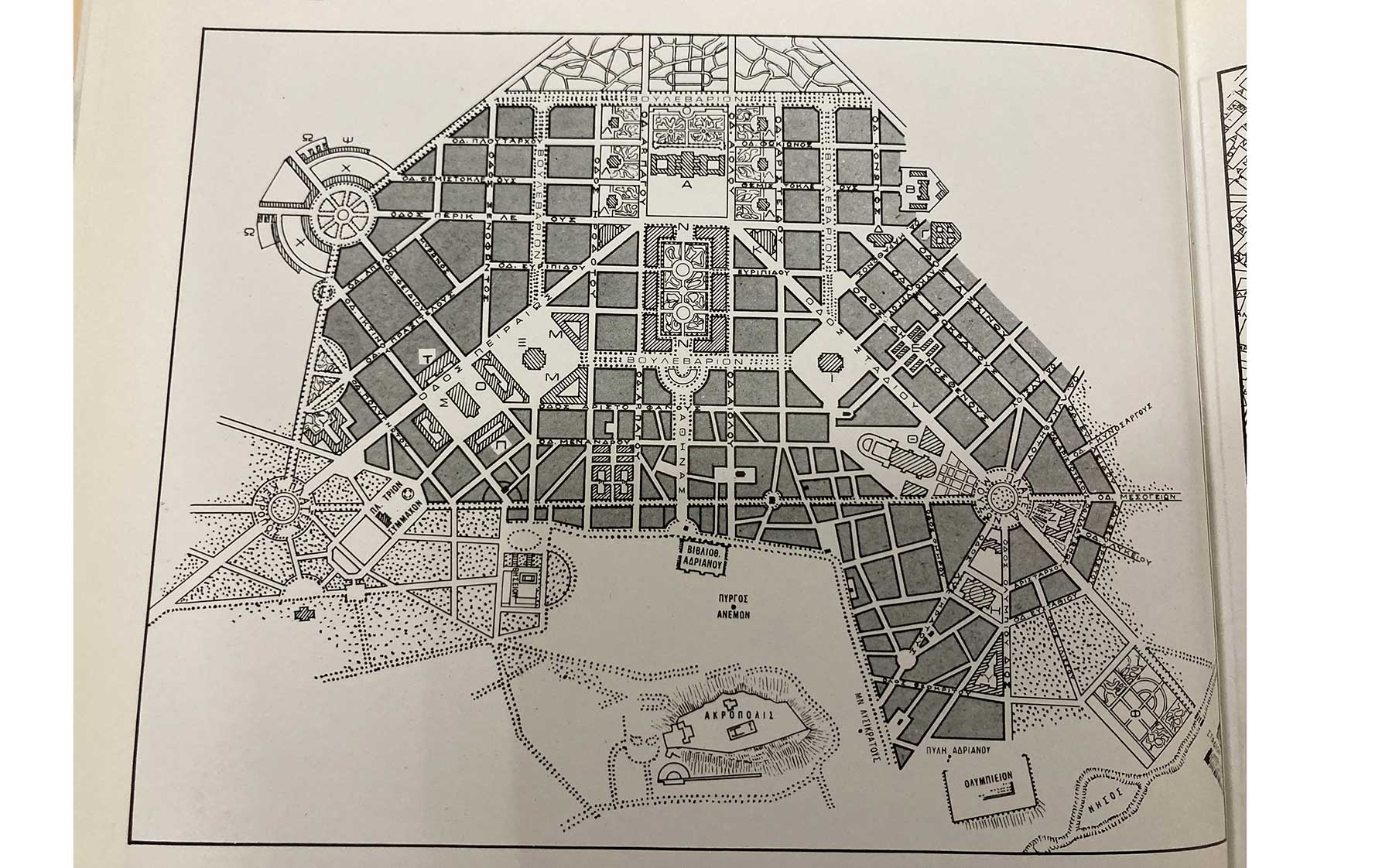

It all began with the realization that Athens really isn’t an ancient city, but a thoroughly modern one. It doesn’t exist next to extensive ruins, like Rome, doesn’t include a medieval quarter, like Barcelona. Nor is it a grand 19th-century capital, like Paris or Stockholm. Despite its pedigree, Athens is a city that was built from the ground up after Greece won its independence in 1830. In fact, it was imagined and planned as the brand new capital of an emerging post-imperial nation-state, a blank canvas on which to project grand ambitions and wild dreams, very much like Washington or Brasilia. As such, its urban core exhibits broad boulevards, large squares, and monumental neoclassical public buildings echoing the names of their European architects: Eduard Schaubert, Stamatis Kleanthis, Ernst Ziller or Theophil Hansen.

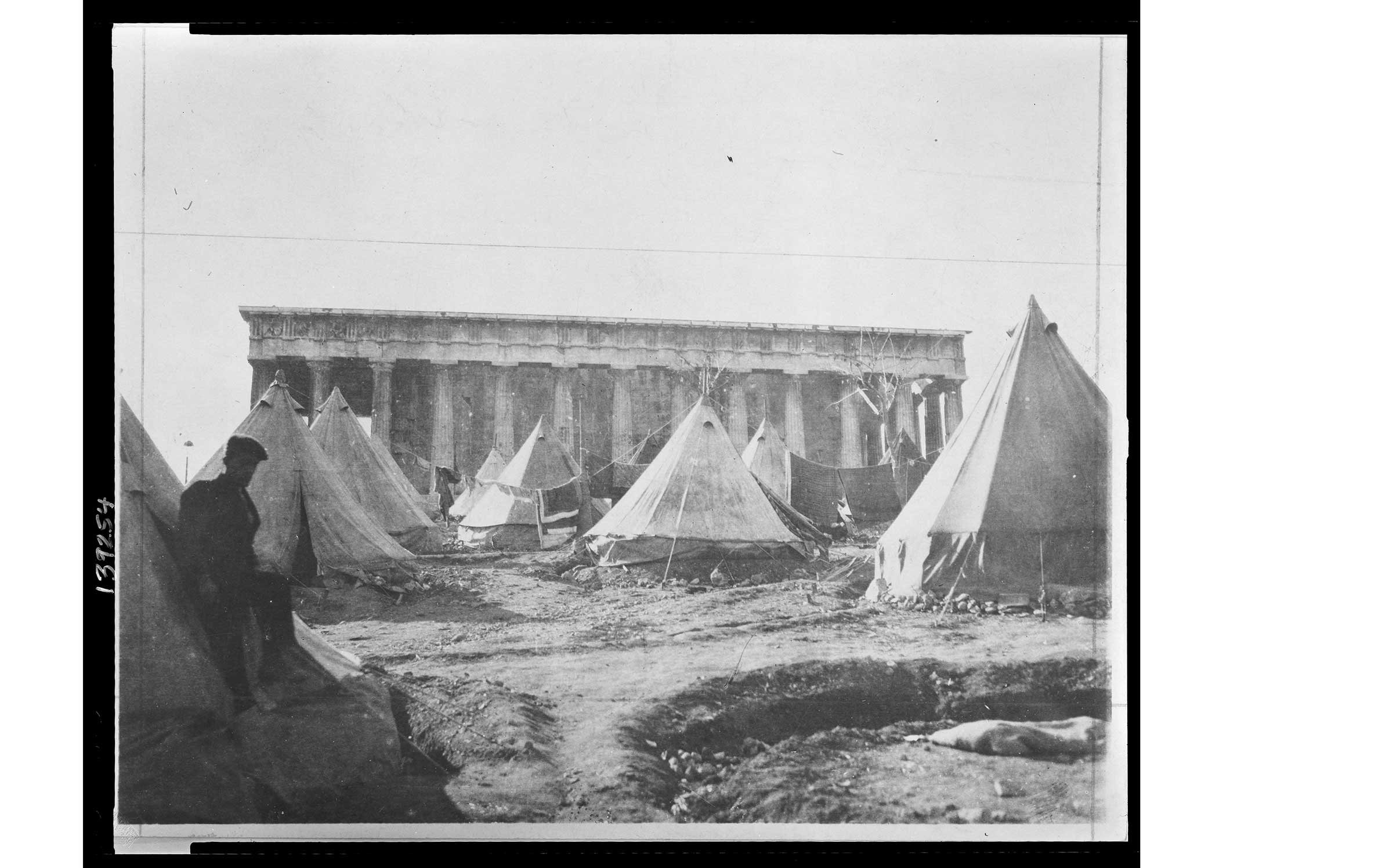

© G. IOANNOU, ATHENS THROUGH POSTCARDS OF THE PAST, I. SIDERIS, ATHENS 2001

But that was only the start. It was the city’s great misfortune (or was it fortune?) that the Greek state lacked the resources to fully realize its highly ambitious original plans. Hence, the city’s development followed a nonlinear path.

During the 19th century it grew to reflect the needs and vision of a growing public bureaucracy and a rising commercial bourgeoisie, including Greeks who’d amassed their fortunes abroad but felt the urge to make a statement in Athens. During the 20th century, however, the city’s development was dictated primarily by a series of shocks caused by wars and mass population displacements. In fact, present-day Athens is the combined outcome of four great waves of migration.

First came hundreds of thousands of Greek Orthodox refugees fleeing Asia Minor after Greece’s defeat by Turkey in 1922. Three decades later, it was the turn of peasants fleeing civil war and seeking economic opportunity. In the early 1990s came a big post-communist, mainly Balkan, wave of migrants, and since 2000, Athens has been attracting people fleeing the war zones of Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia. The city reacted to these successive waves in predictable ways: initially with panic and disbelief, followed by adaptation and integration. How Athens integrated these new arrivals says a lot about why the city looks and feels the way it does today. Indeed, the remarkable thing about Athens, and one often ignored by both visitors and locals, is how (and how well) it has managed to integrate these successive migration waves.

Housing sudden and large influxes of people is perhaps the greatest challenge faced by cities. Developed countries have relied mostly on massive public housing, whereas developing ones have accommodated them through the rapid spread of informal settlements. Athens came up with an original solution that fell right in the middle between Soviet-style blocks and third-world favelas. It did so by using an ingenious legal innovation called antiparochi, a legal framework that opened the door to an unusual transaction: the exchange, effectively a barter, of (present) land for (future) apartments. This approach solved a key obstacle to the provision of affordable housing: limited liquidity and credit. With antiparochi, developers were able to build without the need to purchase land, effectively devoting their limited capital to construction; and landowners could turn land into apartments at no cost to them. Add to this the social makeup of Athens, characterized by small-scale local family businesses and highly fragmented land ownership, and you get the Athenian recipe for rising to its housing challenge.

The literal and metaphorical building block that came out of antiparochi was the polykatoikia, or aparment building, the instantly stereotypical Athenian housing unit. Despite variations, its essential elements have not changed much: usually of medium height (five to six floors) and medium size (a dozen or so apartments on average), it is built out of reinforced concrete with flat roofs and extensive balconies. It is the aggregation of thousands of polykatoikias that has produced an ocean of concrete, the Cement City, that offers such a striking spectacle from any elevation.

© K. MPIRIS FROM THE BOOK “AI ATHINAI”, MELISSA PUPLICATIONS

In their heyday, polykatoikias weren’t just an economical and convenient way to house newly arrived migrants; they were also a point of entry to a new way of living: more densely inhabited and more constricted compared to traditional village houses, more anonymous but also freer, and also incomparably more comfortable, with indoor plumbing and other modern amenities. Most importantly, the polykatoikia performed three key functions very well. First, it spurred social integration and mobility, by conjoining poorer families in the smaller and cheaper apartments of lower floors with wealthier ones in the more expensive and expansive ones higher up. Second, it fostered a broad mix of professional and residential functions, by including an array of shops and workspaces at street level or lower, with business offices (e.g. doctors’ or lawyers’ practices) on lower floors as well. Third, and largely a consequence of this mix, it contributed to the creation of a safe and, ultimately, very lively street ecosystem. The immense concrete jungle one sees from above turns out to be surprisingly human and pleasant when approached at street level.

In short, it is no exaggeration to say that, throughout its history, Athens has been an astonishing integration machine. And it is the resulting energy and vibrant nature of Athens’ street life that many visitors, and increasingly many locals as well, find so enticing and alluring. Which, in turn, explains why Athens has emerged as such an attractive destination recently. But then, why was it overlooked for so long?

© YIORGIS YEROLYMBOS

© NOMADIC JULIEN/UNSPLASH

READY TO SHINE

The 2010 crisis dealt Athens a heavy material and reputational blow – as it did to Greece, more generally. However, the truth is that Athens had reached its lowest point much earlier, during the 1980s. The breakneck speed of economic growth during the preceding 30 years, which had led to massive population growth and an accompanying surge in car ownership, along with a chronic lack of investment in public infrastructure, ended up producing a disastrous cocktail of dysfunctional results: hellish traffic jams and deadly air pollution known as the nefos (cloud), which made air unbreathable and covered the city in a grey haze. This caused a massive population flight from the city center to the suburbs, as well-to-do Athenians sought cleaner air, more personal space and more greenery, leading to the desertion of vast downtown areas.

When the last wave of migrants arrived from Africa and Asia, they settled in these abandoned areas, an ideal setting for generating social stress, further exacerbated by the financial crisis that erupted in 2010. Still, that crisis failed to erase the vast improvement that had been achieved in the preceding years. Indeed, Greece’s 2004 Olympic Games had spurred major, and effective, air and sea clean-up initiatives alongside massive investments in public infrastructure, including a new airport, a new ring road, and a gleaming new subway system.

So, when Airbnb and budget airlines arrived in the mid-2010s, Athens was ready to shine again and impress this new wave of visitors with its unique energy and atmosphere, now updated and enhanced by a host of creative and talented designers, architects, shop owners, and restaurateurs – many with a cosmopolitan pedigree. In turn, these visitors were happy to give Athens a chance, exploring it more thoroughly and discovering its modern personality even as they continued to appreciate its famous ancient gems. And it’s this, perhaps, that was needed to get Athenians to see their own city with a new set of eyes and start to show it the love it deserves.