A Summer Visit to the Acropolis: What Tourists...

Tourists share the highs and lows...

Cavo Paradiso

© Johnny Panopoulos

Mykonos is an exceptional case, not only in the Aegean but in the Mediterranean in general: an archetypal cosmopolitan island of dreams, desire and hedonism, and, at the same time, a perfect example of tourism-led development, where a subsistence agrarian economy has evolved into a service-oriented one, driven by innovative business practices.

The island has around 11,000 permanent inhabitants and can support up to 10 times that number in the summer months. As a tourist destination, it now possesses an unmistakable identity, albeit one which is still evolving. The media, visitors both famous and “anonymous,” along with the first local entrepreneurs, have all been crucial contributors to this identity, which began to form in the 1930s, when the first tourists arrived on Mykonos.

Mykonos was always open-minded, as is evident from the multiple references to the island made by early travelers from mainland Europe and voyagers on the Grand Tour, from the 11th to the 20th century. Long before the island became part of the global tourism network, it was already part of the extensive maritime and trade networks of the Mediterranean. It sent many an emigrant to Athens and the United States, and also welcomed exiles in the interwar period.

The spark that ignited the tourist trade in the 1930s was the international interest stirred up by the archaeological site on Delos. This was the period when an educated elite of artists, architects and wealthy urbanites “discovered” the island and started giving Mykonos its global character.

By the 1950s and 1960s, Mykonos was already enjoying a worldwide reputation independent of Delos. The “authenticity” of its Cycladic landscape, the hospitality of the locals and the general admiration for its vernacular architecture all came together to form the nucleus of an idea around which the island’s identity as a hot destination was developed.

Fredys Dactylidis, founder of the legendary Paradise Beach, helped shape Mykonos’ image as a tourist destination, injecting it with a free-spirited vibe when he created the island’s first campsite and official nudist beach. Here he is seen happily posing with two tourists in 1999.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Young people partying on Paradise Beach.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Reading the accounts of many visitors of the time and flipping through publications from that era, it’s clear that the encounter with the otherness of the place and its inhabitants was part and parcel of a visit to postwar Mykonos. For many visitors, the island played host to all kinds of unions and syncretisms. Bonding with the Cycladic spirit, with the “divine” element of Delos and Mykonos, became part of a metaphysical appreciation of the place. A feeling of conviviality brought together visitors and locals, celebrities and mere mortals.

Many postcards from the 1960s and 1970s record this type of melding: celebrities, tycoons and politicians arm-in-arm with fishermen in celebration; resident self-taught artists hanging out with their more famous colleagues; beauties and debutantes seated with local boys; youthful groups of western Europeans, Americans and Greeks full of the vacation spirit, sitting at cafés or strolling down the streets of Hora, singing alongside local revelers.

Mykonos had already become what anthropologists call a liminal space, a place of freedom where the rules of everyday life are suspended, a paradise for tourists looking for a break from their Western, work-centered routines, and for others who simply wanted to continue their bohemian, hippy lifestyle on their vacation. The island tolerated the unconventional, and this is one of the reasons why it quickly became a magnet for the gay community.

The addition of basic hospitality services provided an opportunity for fertile cultural exchanges. In the beginning, these services were offered on an ad hoc basis, as there were no proper tourist accommodations and many locals rented out rooms in their family homes to visitors. This is how many friendships – and romances – were born. From that point on, Mykonos became a place of tolerance and exploration. The unconventional and the carnivalesque remain among its main attractions.

In the years that followed, the island opened up even further, offering the combined sale and consumption of “nature” – sun, sea and picturesque Aegean scenery – as well as a playground for the fashionable and wealthy. The many nightclubs, restaurants and designer clothing boutiques painted a picture of Mykonos as a place dealing in style, fashion, images and fantasy.

As Mykonos became a world-renowned destination, the local population faced radical changes in their daily lives. Large expanses of land changed hands and became commercialized, losing its agricultural character to serve the development plans of local and foreign entrepreneurs. A class of elites began to emerge, altering the political and social balance on the island. The businessmen, both local and foreign, created their own socioeconomic group and, by driving development, were central to the new balances that emerged.

In more recent times, the tourism-driven employment market has brought women to the fore as dynamic forces in their own right, with their own financial resources and greater professional freedom. This, in turn, broadened local attitudes, creating new notions of what is acceptable and permissible.

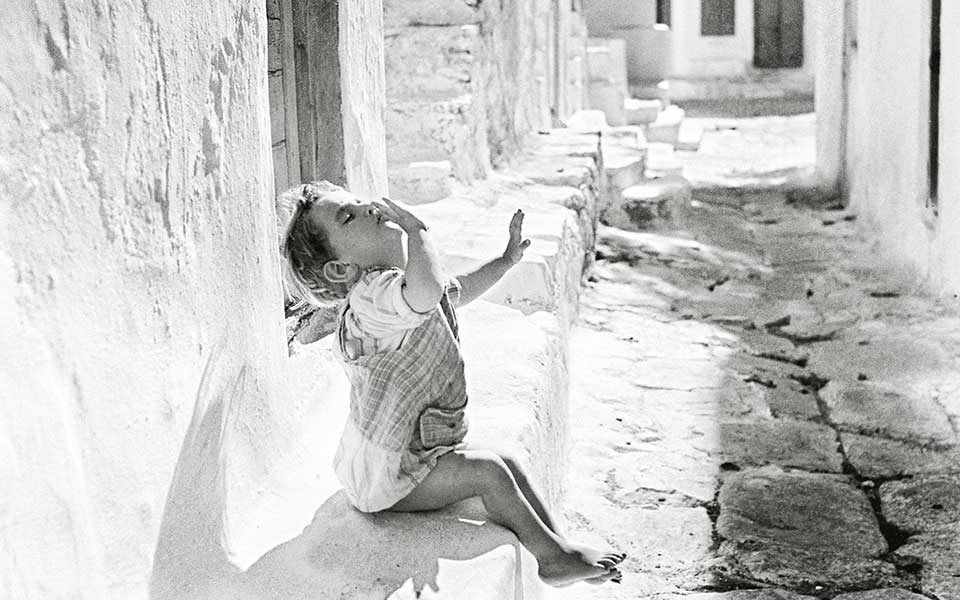

A photograph by Voula Papaioannou, one of Greece’s foremost 20th century photographers, renowned for the way she captured life in the country during more innocent times. Her images of Mykonos depict the island before it was forever changed by mass tourism.

© Voula Papaioannou/Benaki Museum Photographic Archives

Despite the problems created by intensive development, Mykonos is still considered a symbol of cosmopolitanism, a “Manhattan of the Aegean.” After the mass arrival of Greek tourists in previous years, the island is now a top destination for Chinese, Russian and Arab visitors. At the same time, Mykonos is inhabited by people who experience the island in different ways, such as the workers in the tourist industry, seasonal and not, among whom are many economic migrants from eastern Europe, India and Pakistan.

Another cultural group is made up of the various foreigners, primarily Europeans and Americans, who have started businesses, bought homes and land, and live on the island year-round. Among the other population groups that share the island are Greeks from different parts of the country who view it as a place to make a living or find success during difficult economic times.

Today, one might argue that Mykonos is defined more by cosmopolitan traits than by its traditional values or by stereotypical notions of local culture. Still, glimpses of the cultural codes of an older, agrarian world – evidence of which you’ll find in local island groups, nicknames, religious ceremonies and feasts – can still be seen at times. Meanwhile, issues of collective memory and indigenous symbols are becoming the focus of the many cultural associations on the island trying to preserve local identity in the midst of a shifting social landscape.

Despina Nazou is a social anthropologist. She is an affiliated lecturer at the University of the Aegean and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Crete. This article first appeared in Greece Is – Mykonos, 2018 Edition.

Tourists share the highs and lows...

On Mykonos, this simple yet vibrant...

Discover Leros, a hidden Greek island...

Your summer map to Ios: what...