The Secrets of Amalias Avenue

Discoveries along Amalias Avenue, from the...

The members of the first International Olympic Committee. From left: Willibald Gebhardt (Germany), Pierre de Coubertin (France), Jiri-Guth Jarkovsky (Bohemia), Dimitrios Vikelas (President, Greece), Ferenc Kemeny (Hungary), Alexei de Butowsky (Russia), Viktor Balck (Sweden).

© Albert Meyer, Benaki Museum Photographic Archives

“It is clear that the telegraph, railways, the telephone, the passionate research in science, congresses and exhibitions have done more for peace than any treaty or diplomatic convention. Well, I hope that athletics will do even more…

Let us export rowers, runners and fencers: there is the free trade of the future, and on the day it is introduced within the walls of old Europe the cause of peace will have received a new and mighty stay…

This is enough to encourage your servant to dream now… to continue and complete, on a basis suited to the conditions of modern life, this grandiose and salutary task, namely the restoration of the Olympic Games.”

Thus, in 1892, Pierre de Coubertin, a French aristocrat, delivered a speech that may have been the most significant public call for the creation of the modern Olympic Games. “International competitions” was its theme. But it was not the first. More than half a century before, in his poem Dialogues of the Dead, the Greek poet Panagiotis Soutsos imagined the ghost of Plato speaking to the newly independent but devastated Greek nation: “Where are all your theaters and marble statues? Where are your Olympic Games?” Now, finally free of Ottoman suzerainty, where were its great spectacles, arts and athletics? Soutsos was sufficiently fired by this thought that he made a proposal to the Greek state that it should revive the ancient Olympics.

In the 60 years between Soutsos’ poem and Coubertin’s address, there would be dozens more Olympic events, recreations and spectacles, now shaped by the emergence and globalization of modern sports and the archaeological excavation of Olympia itself. Soutsos was the first to call for a revival of the Games; Coubertin was the first to bind that notion to some form of internationalism and make it happen; but both ideas emerged from a long and bizarre encounter between European modernity and an ancient religious festival about which only fragments are known.

As the dominant world power of the 19th century, Victorian Britain might have seemed an obvious Games-revival catalyst. However, it was not Britain’s public schools or Oxford and Cambridge universities, thick with aristocratic sportsmen and classicists, that took on the Olympic idea, but Dr William Penny Brookes, a doctor from the small Shropshire market town of Much Wenlock. In 1850, he inspired the first Much Wenlock Olympian Games, deemed a forerunner of the modern Olympics. Eclectic in every way, the games were part rural fair, part school sports day. As they grew more popular, Brookes added processions and pageantry, poetry competitions, shooting, cycling and an ever-changing pentathlon. The odd classical reference aside, Much Wenlock’s Olympian credentials were always rather thin.

Brookes was among those English proto-Olympians who met in London in 1865 with a view to forming a National Olympian Association (NOA).They envisaged an organization that could “bring into focus the many physical, athletic and gymnastic clubs that were spreading all over the country,” and could stage national games open to “all comers” – a proposal that did not include women or professionals, but at least on the matter of class origins, it was neutral. London was the group’s natural choice as the venue for the inaugural NOA games in 1866. However, rivalries with other groups ultimately thwarted its efforts.

“This is enough to encourage your servant to dream now… to continue and complete, on a basis suited to the conditions of modern life, this grandiose and salutary task, namely the restoration of the Olympic Games.”

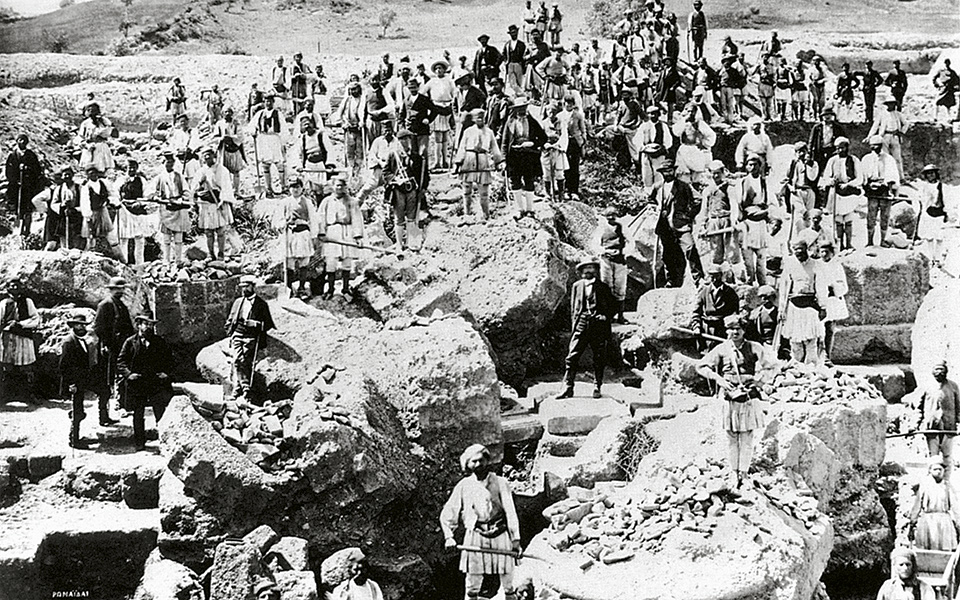

Excavation site with workmen and archeologists at the temple of Zeus, Olympia, 1875-1876. (German Archaeological Institute)

© German Archaeological Institute

Hellenic pretensions carried a lot more weight in modern Greece, where Soutsos issued the first call for the revival of the games just a few years after independence. Soutsos’ most important convert to the cause was the shipping magnate Evangelos Zappas. In 1856, seeking a legacy for his fortune, Zappas wrote to King Otto proposing a revived Olympic Games to be held in a renovated Panathenaic Stadium, with prizes for the winners, all paid for by a very considerable financial bequest. The government replied that money might be better spent on a building that could house a quadrennial exhibition of Greek agricultural, industrial and educational advances, with a single day reserved in the program for athletic games and amusements. A deal was reached in 1858, and the first Zappas Olympic Games were held in 1859.

Staged in a cobbled city square in Athens over three Sundays, there were running, horse and chariot races, discus and javelin competitions modeled on the testimony of ancient sources, as well as the climbing of a greasy pole. The games were opened by the king and queen, medals bearing the words First Olympic Crown were issued and prizes were plentiful. The crowds appear to have been large, athletes came from across the Greek-speaking world to attend, but the organization was poor.

In 1865, Zappas died, leaving much of his huge fortune to the continuing task of reviving the games. Otto was now in exile; he had been replaced in 1863 by George I, a teenage Danish prince. An enthusiast for sports, and conscious of his limited Hellenic credentials, George readily backed the staging of a second games in 1870, once again as part of a bigger agro-industrial festival. Using just a portion of the Zappas bequest, the Panathenaic Stadium was partly rebuilt, a small grandstand was erected and considerable travel expenses and prizes were offered to athletes traveling from all over the Greek-speaking world. The games were deemed a great success and attracted a crowd of 30,000, but some were appalled by the presence of athletes from the working class. At the next games, in 1875, only athletes from the “higher social orders” would be allowed to compete. Despite the glee in the press that the games would be “much more respectable,” they were a disaster.

Not surprisingly, the Zappas Olympic committee kept a rather low profile for the next decade. They proposed a fourth Zappas Games, but the committee never really had its heart in it. Revivalism survived in the form of the newly formed Panhellenic Gymnastic Society – the center of aristocratic sport in Athens – which held its own small Panhellenic Games in 1891 and 1893, attracting both King George and Crown Prince Constantine as spectators and patrons. In 1890, Constantine went so far as to sign a royal decree announcing that a four-year cycle of Greek Olympics would begin again in 1892. However, if the Greek monarchy and its allies wanted to revive the Games, they were going to need support from somewhere else.

“In 1856, seeking a legacy for his fortune, Zappas wrote to King Otto proposing a revived Olympic Games to be held in a renovated Panathenaic Stadium, with prizes for the winners, all paid for by a very considerable financial bequest.”

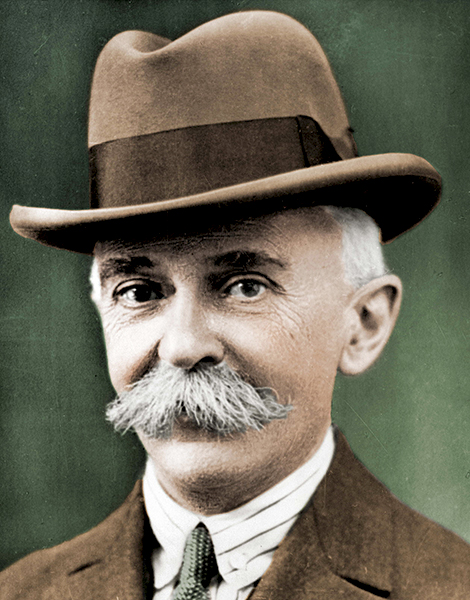

Portraits of Baron Pierre de Coubertin (18631937), from his childhood years

© The Olympic Museum, Getty Images/Ideal Image

...to 1896, when he realized his dream of reviving the Olympic Games

© The Olympic Museum, Getty Images/Ideal Image

Pierre de Coubertin’s body may lie in Lausanne, with his heart buried at Olympia, but he hailed from France and was definitively shaped by its political travails. Born in Paris in 1863 as Pierre de Fredy, Baron de Coubertin, he was the fourth child of a long-established aristocratic family.

By the time Coubertin left his Jesuit school, the outwardly conformist schoolboy had decisively broken with the key beliefs of his parents, rejecting a career in the priesthood. He enrolled at the elite Ecole Libre, where he took a variety of whatever classes happened to please him. It was an intellectual atmosphere of experimentation and iconoclasm that suited him well. But, as useful as studying was, Coubertin clearly yearned for something more in keeping with his status as an aristocrat, a person of standing in the world.

For most of the 1880s, Coubertin was a man in search of a role, a grander and higher mission and purpose. The key for Coubertin was travel, and it was his time in Britain and the United States that allowed him to focus his interests in sport, educational reform and national development.

His English travels are best understood as a series of glorious confirmations of his own reading of the bestselling Tom Brown’s School Days – by Thomas Hughes, a pupil at Rugby school in the 1840s – which came to define the meaning of the public-school experience of the games ethic for generations. On close reading, its ponderous didacticism, moral pomposity and cloying sentimentality is occasionally shot through with more subversive meanings – a barely concealed homoeroticism, flashes of real human warmth and a disdain for the cruel and violent excesses of these appalling institutions. But Coubertin was never a man for close reading.

In his view, English public school team sports offered an arena for the cultivation of a manly physique and a gentlemanly disposition. Competitive but not cut-throat, they inculcated respect for authority and the rule of law without crushing individuals. The wider athletic culture aspired to the Hellenic virtues of a balance between mental and physical health. Above all, it reserved a place for glory and honor, bravery and valor. Coubertin’s distillation of the public-school games ethic would in time form a core component of his syncretic notion of Olympism.

Coubertin had his cause, but now he sought action. In 1888, he helped form and run the General Committee for the Propagation of Physical Exercise in Education, which, two years later, fused with a smaller competitor to create the Union des Societes Françaises de Sports Athletiques (USFSA). Opponents, deeming it too anglophile, created a rival organization that even called for the creation of a French version of the ancient Olympic Games. Amazingly, just three years before he would launch his own brand of revivalism, Coubertin was dismissive of the notion, even a little contemptuous. Yet this is precisely what he would go on to create, while the revival of the Olympic Games would become, for him, the cause of all causes, combining innumerable personal and political, sporting and intellectual strands in his life.

There is no doubt that Coubertin’s Jesuit education would have ensured he was familiar with some of the classical texts on the Games, but he was probably also aware of some of the information emerging from the German excavations at ancient Olympia.

“While the revival of the Olympic Games would become, for him, the cause of all causes, combining innumerable personal and political, sporting and intellectual strands in his life.”

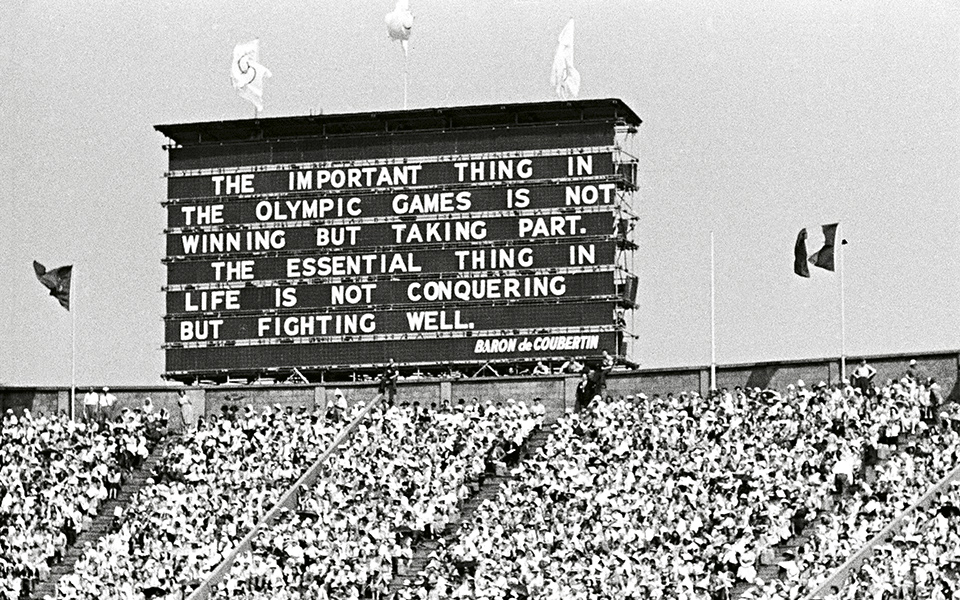

A scoreboard bearing a quote by the founder of the modern Olympics, Pierre de Coubertin, at the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in London’s Wembley Stadium, 29 July 1948.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

However, the most likely explanation for Coubertin’s volte-face, at the very least the catalyst for his change of mind, was his encounter with Dr Brookes and the Much Wenlock Olympics.

In early 1889, Coubertin had put out a call through the columns of English newspapers for correspondents who would care to communicate on the matter of physical education. Dr Brookes was one of his respondents, sending him a steady stream of Olympic-related letters, cuttings and reports. In his later correspondence with Brookes, which resulted in an agreement to attend the Much Wenlock games in October 1890, the issue of the ancient Olympics did not arise. The sport really wasn’t much to write home about, but Brookes went big on pageantry.

Competitors arrived in elaborate costume and processed through a stage-set triumphal arch. The field was decorated with banners in ancient Greek, quoting the classics. The games themselves were short: eclectic track and field events were followed by tilting at the ring and an elaborate faux-medieval prize-giving. The doctor also introduced the baron to his scrapbooks, his Olympics-revival archive and correspondence, and his personal library – as well as, during the course of this, the history of both his National Olympian Association, the various Zappas revivals and his own subsequent exchanges with the Greeks.

Something must have clicked. On his return to France, Coubertin wrote an article about Much Wenlock. Coubertin made it plain, as he would never do again: “If the Olympic Games which modern Greece could not bring back to life are revised today, the credit is due not to a Greek but to Dr Brookes.”

It seems indisputable that it was only in the months after his visit to Much Wenlock, that Coubertin became an Olympic revivalist. In the 18 months between the publication of his Much Wenlock article and his 1892 speech at the Sorbonne, where he first proposed an Olympic revival, he forged a unique version of the modern games. Moreover, unlike his predecessors, he would be able to create an international social and political coalition that could make it happen.

Perhaps Coubertin’s greatest advantage was his capacity to think big. He fused his Olympic revivalism with the most universal call of all – internationalism – envisaging the games not as a recreation or a country fair, but as a grand, if restrained, urban cosmopolitan spectacle; and he had the personal connections and ideological appeal that could tie the revival of the Olympic Games to the gentlemen athletes of the industrialized world.

Although he had rejected a career in diplomacy, one of the few avenues open to him, Coubertin’s social rank and connections made him a natural part of the world of international affairs.

The most effective way of mobilizing these forces was on the question of amateurism in sport, and to make it the common task of international congresses to discuss, propose and try to set international norms in their field of expertise.

There was a final component in the mix: to revive the ancient Games, even under modern conditions, was to enter the realm of the sacred. Coubertin recognized and was greatly attracted to the indelibly religious character of the ancient Olympics. The Catholic aristocrat, searching for glory and heroes, marooned in an increasingly demotic and secular world, had found his vocation, his gods and a stage on which to venerate them.

“Perhaps Coubertin’s greatest advantage was his capacity to think big. He fused his Olympic revivalism with the most universal call of all – internationalism – envisaging the games not as a recreation or a country fair, but as a grand, if restrained, urban cosmopolitan spectacle”

Spectators entering the Panathenaic Stadium, at the 1896 Olympic Games in Athens.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

In 1892, less than two years after his Much Wenlock visit, Coubertin gave his famed speech at the Sorbonne, at a conference held to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the foundation of the USFSA. The early responses were not good. Some in the audience, thinking the whole thing an elaborate pageant, joked as to whether the athletes would be naked.

Undeterred, Coubertin looked for other opportunities to make his pitch and, in 1893, a friend suggested the USFSA host an international conference on the principles and problems of amateurism in the sporting world.

Coubertin seized on the opportunity, suggesting that his Olympic idea might also form a small element of the discussions.

Initial interest was thin. Trips to the USA and Britain in late 1893 failed to drum up any public support or interest, but, during the spring of 1894, the baron assembled the other essential components of the congress.

A French state senator and former ambassador to Berlin was persuaded to act as a figurehead. Moreover, the letterhead of the congress was gilded by an enormous list of Coubertin’s correspondents, including many in Europe’s royal houses.

On the final set of invitations, the meeting was now known as the International Athletic Congress and the Olympics component had crept up the agenda. Coubertin had also been working the Greek back-channels and secured two key allies. First, Prince Constantine agreed to be an honorary member. Second, Coubertin acquired a Greek delegate to the congress who would be able to make the case for him that Athens should be the first host city: the elderly Greek writer Dimitrios Vikelas. Coubertin asked him to chair the committee that would deal with the revival of the Olympic Games.

Coubertin’s congress attracted 78 delegates from sports clubs and organizational bodies, drawn mainly from France and predominantly from Europe. Proceedings opened in the great amphitheater of the Sorbonne, where the audience heard the recently discovered and translated Hymn to Apollo, a classical ode set to music by the composer Gabriel Faure. Coubertin thought they listened “with religious silence to the divine melody which lived again to salute the Olympic revival across the dimension the ages,” and that “Hellenism infiltrated the whole hall.”

“Proceedings opened in the great amphitheater of the Sorbonne, where the audience heard the recently discovered and translated Hymn to Apollo, a classical ode set to music by the composer Gabriel Faure. ”

Preparation for the 100m race in the Panathenaic Stadium, photographed by Albert Meyer, official photographer of the German delegation to the 1896 Olympics.

© Albert Meyer/Benaki Museum Photographic Archives

Back at the Sorbonne, the two committees got down to work. At the opening session of the Olympic committee, there was a strong case made for London as the inaugural host, rather than Athens, but with his consummate committee skills, Coubertin persuaded the meeting to leave the question open. Then, at the decisive moment, Vikelas spoke to the congress, advocating an Athens games: “A Greek institution was being revived for which a Greek city was an appropriate host,” he said. Much to the baron’s surprise, Vikelas’ suggestions were warmly received.

The congress went on to confirm that the first games should be held in Athens in 1896, the next in Paris in 1900. Under the strict terms established by the congress’ other committee, they would be open only to amateurs, with the exception of fencing masters. A permanent committee was established, with Vikelas as its titular president and Coubertin as the general secretary.

The congress may have finished on a high, but the award of the Games was not well received by the Greek government of Prime Minster Harilaos Trikoupis, which argued that, given the economic situation, Greece could not host the games.

Despite official opposition, Coubertin was able to convene a meeting at the Zappion to discuss plans for the games. Coubertin had a few allies among the assembled Greek gentlemen, but most were active supporters of Trikoupis. Coubertin announced that Prince Constantine had agreed to act as honorary president and that the bill for the Games really wouldn’t be as much as they imagined. He then chose four vice-presidents and declared them the organizing committee of the 1896 Athens Games.

Not long after his return to France, however, Coubertin learned that the committee he had left behind later got cold feet and collectively resigned. Into this vacuum stepped the royal house and, in particular, Prince Constantine. He established and steered a new organizing committee, mobilized the monarchy’s own networks of supporters, traded favors and began preparations. An initial series of public donations were supplemented by a huge gift from Georgios Averoff, a rich Greek businessman living in Alexandria. Almost a million drachmas enabled the ancient Panathenaic Stadium, already partly renovated for the previous Zappas Games, to be completely rebuilt and reclad in marble.

The final months of preparation offered many of the tropes that still structure Olympic coverage a century later. Rumors persisted that the stadium and other facilities would not be ready on time. But start on time they did, on Greek Independence Day (March 25) as Panagiotis Soutsos had argued for over half a century earlier.

However, it was Coubertin’s intervention that really ignited a serious and sustainable Olympic revival movement.

“Rumors persisted that the stadium and other facilities would not be ready on time. But start on time they did, on Greek Independence Day (March 25) as Panagiotis Soutsos had argued for over half a century earlier”

David Goldblatt was born in 1965 and taught the sociology of sport at Bristol University, De Montford University, Leicester and Pitzer College, Los Angeles. He has published highly acclaimed books on soccer. This article is based on the first chapter of this latest book, The Games: A Global History of the Olympics (Macmillan, 2016).

Discoveries along Amalias Avenue, from the...

A summer mix of cultural events...

We join archaeologist and MONUMENTA coordinator...

A personal exploration of Koukaki and...