Lesser-Known Traditions of Greek Easter

Step off the beaten path this...

Aristophanes’ “The Birds,” staged by Alfredo Arias at the Comedie Francaise in Paris, on April 2010

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Laughter predates the comic. In the Iliad, Thersites, the worst of the Achaeans who sailed against Troy, according to Homer, ugly, hunchbacked and vulgar, addressed the Greek army as it was rallying solely to mock and to make the others laugh. A forerunner of Aristophanes’ characters, in the end he is forced to depart in tears when Odysseus strikes his hump with Agamemnon’s scepter.

A nobler version of this very human response is the laughter of the gods. As is known, unlike Christian saints who are never portrayed even smiling in icons, the Greek gods enjoyed having a good laugh. In fact they would often roll about laughing, as in the famous episode in the Odyssey in which Hephaestus caught his wife Aphrodite in the arms of her lover, Ares, in an unbreakable net that he himself had fashioned. Hephaestus assembled the other gods to reveal the scandal, hoping for retribution, but they simply roared with laughter at his predicament. Divine laughter, perhaps, but by today’s standards laughter that would be more common in a military camp of new recruits. And when you think about it, even believing that the proletariat of the gods – the crippled blacksmith Hephaestus – is married to the most attractive and erotic of all the beautiful goddesses, means you must have a healthy appreciation of the ridiculous.

So, the gods were laughing, the kouroi and korai were smiling, but democracy in the 5th century BC gave laughter a place among the other institutions of the city. Deriving from the komos, the Dionysian procession of drunken revelers who danced along the streets, ridiculing each other and passersby, comedy performances gained a prominent place in theatrical contests. These competitions, featuring dithyrambs, tragedies, satyric dramas and comedies, would have been the equivalent of today’s Hollywood. They were held in early spring, when the sea lanes were open and citizens of allied cities on the islands would flock to Athens to conduct their legal, commercial, tax and other affairs. The theater on the south slope of the Acropolis, in the shadow of the Parthenon, or of the construction sites before its completion, could accommodate an audience of roughly 25,000 men, women and metics.

“ Democracy in the 5th century BC gave laughter a place among the other institutions of the city. Deriving from the komos, the Dionysian procession of drunken revelers who danced along the streets, ridiculing each other and passersby, comedy performances gained a prominent place in theatrical contests. ”

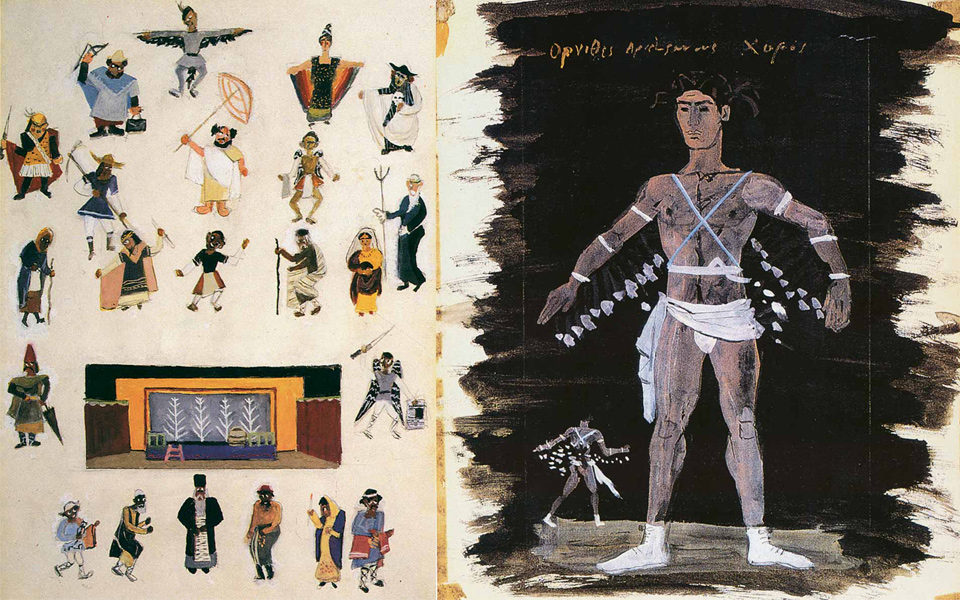

Costume and set designs by Karolos Koun for Aristophanes' "Plutos" (L) and "Ornithes" (R)

It is certainly worth imagining what may have happened when a particularly good joke passed from the stage to the audience; their loud yells, their laughter, their retorts, all in an atmosphere of heavy human odors made even heavier by the consumption of garlic and shallots. The Athenians were not known for refinement in their social behavior. But it is worth noting that the democracy was not afraid to show to the entire Greek world its basest aspects; it didn’t hesitate to ridicule itself by brutally exposing the flip side of political virtue: sycophancy, litigiousness, greed and demagoguery. And it’s even more startling when one considers that all these performers on the stage, breaking wind, belching and getting drunk in front of a Chorus whose members sported huge phalluses, were the same people who built the temple of harmony and balance, the Parthenon, in whose shadow they played out their degradation – yet more proof that the Greeks had to go to the furthest extremes before appreciating the value of moderation.

In contrast with tragedy, which sought its characters from among the heroic figures of mythology, comedy focused on day-to-day public life. Initially, performances were similar to contemporary Vaudeville: A show consisting of comedy sketches and gags targeting public figures, complete with slaps, kicks and bodily noises. Lots of music and song. The actors, males only of course, would quarrel among themselves about who should be entrusted with the show’s big hit. This is how Aristophanes learned his comic art at the side of his teacher, Cratinus, and began honing it in the mid-420s BC when still very young, not yet 25. If today, Aristophanes is still considered to be the “father of comedy”, it is because he was the first to give his art a dramatic structure; he created realistic plots in which he immersed his characters, while at the same time adding a political dimension to the comedy. It is generally accepted that laughter is the most elusive element in literary expression. The spectator, or reader, of the 21st century may understand the tragedy of Medea, abandoned by Jason, but it is by no means certain whether he or she laughs for the same reasons that the audience in ancient Athens laughed at the buffoon Strepsiades in “The Clouds”, or at Bdelycleon and Philocleon in “The Wasps”. But he or she definitely comprehends the directness and bluntness of the criticism leveled by an Athenian of the period against the democracy that we today consider to be the single most important achievement of 5th century BC Athens.

“Athenian society had such confidence in its strengths that it did not fear self-ridicule. It is probably no coincidence that the creation of the great tragedies, as well as of the remarkable comedies of Aristophanes, comes to an end with the city’s defeat in the Peloponnesian War. ”

Scene from the historic Art Theater production of “The Birds” in 1959, directed by Karolos Koun. The music was written by Manos Hadjidakis, with stage sets and costumes designed by painter Yannis Tsarouchis.

© Corbis/Smart Magna

The miracle of a society that experimented with the condition of its co-existence (for democracy began as an experiment), lasted less than a century, but still occupies us today. As does the courage of a society, but also the courage of its citizens and of its dramatic poets who performed a public function. Outspokenness was an obligation of Athenian citizens when they took the floor in the Ekklesia, but without it the comic poet could not serve his art. Outspokenness to the utmost degree, whether in terms of foul language or deliberate exaggeration, or the intentional distortion of characteristics in order to highlight them, even ridicule them, without which laughter cannot be produced. And what remains captivating about Aristophanes’ comedies is the fact that the laughter they provoked was the result of withering criticism of the people and processes of democracy. Aristophanes does not create comic situations to provoke laughter, like today’s ridiculous TV “stars.” He creates comic situations to judge people and things, and the laughter that he may succeed in provoking is the result of his judgment. At this point, one must be careful. The comic poet, under the protection of Dionysus, had the right to judge the people and things of the democracy to the utmost degree. But he was prohibited from denouncing the polity itself. What we forget today is that democracy was born and developed along with a very strict observance of certain limits.

Just consider, however, how much courage it took on the part of that young Athenian, not yet 25 years old, with his city at war, to place on the stage a wretched peasant, Dikaiopolis, who desires peace with the mortal enemy, Sparta. While also seizing the opportunity in the same play to taunt the great tragedian Euripides. “The Acharnians” is the earliest of Aristophanes’ surviving plays and was followed, one year later, by “The Knights.” Here, the target is Cleon, a quarrelsome, warmongering demagogue who dominated Athenian politics a few years after the death of Pericles. In the play, Cleon helps Demos (“the people”) get drunk so that he can do with him as he pleases. In order to rid themselves of his influence, the Athenians choose someone even worse. “If you want to deal with something bad, find something even worse” – the conclusion reached by Aristophanes may have made his fellow citizens laugh, but it sounds like an “all-weather” political theorem. As we said, comedy has its limits. Those Athenians who applauded Cleon’s vilification and handed Aristophanes the first prize at the annual Lenaia festival were the same Athenians who, just a few months later, again elected Cleon as strategos (general). In “The Clouds,” it was the turn of Socrates to be lampooned. A real roasting, no holds barred! Aristophanes portrays Socrates as a shyster headmaster who does not believe in the city’s gods and teaches his students how to talk their way out of paying their debts – a lesson that certainly has resonance in present-day Greece. To understand the power of comedy, one has only to consider that at his trial 25 years later, Socrates began his defense by saying he feared the comic playwright who had portrayed him as a fraud more than his accusers. A quarter of a century after his “conviction” by Aristophanes, the judgment was upheld.

“ What remains captivating about Aristophanes’ comedies is the fact that the laughter they provoked was the result of withering criticism of the people and processes of democracy. Aristophanes does not create comic situations to provoke laughter. He creates comic situations to judge people and things, and the laughter that he may succeed in provoking is the result of his judgment. ”

English actress Joan Greenwood (1921-1987, center) in the title role of Aristophanes' classical Greek play "Lysistrata," an English Stage Company production, directed by Minos Volonakis, London, 1957.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

And what of women? One cannot speak about Aristophanes without referring to the classic Lysistrata. At the very least, it overturns some of the most deeply entrenched stereotypes about Athens in the Classical period. Just imagine if, of all the ancient writings, only the comedies of Aristophanes had survived. We would no doubt believe that Athens had been a society dominated by women, in which the only thing that men knew how to do was kill each other in war. All other things, the serious matters, were handled by women.

Fortunately however, in addition to the works of Aristophanes, along with that huge volume of thinking and human experience handed down to us from the period, we also have the writings of Plato. In his philosophical text “Symposium,” Plato presents the comic playwright giving a speech in which he explains to those at a drinking party that love was born when Zeus decided to chop in half the spherical creatures, namely people, who until then had double bodies with faces and limbs turned away from one another. Since that time, one half has been searching for the other. And when at the end of the symposium, as dawn was breaking and everyone else had fallen asleep in a drunken stupor, Socrates explains to Aristophanes that a skilful playwright should be able to write comedy as well as tragedy. Years later, in Book X of his “Republic,” Plato concludes that all comic and tragic poets should be banished from the ideal city (Kallipolis), because they incite the passions instead of the faculties of reason. Plato’s “Republic” is in effect a rejection of the democracy that made Athens what it was in the 5th century BC, while in condemning comedy and tragedy, Plato demonstrates just how closely intertwined they are with the democratic institutions of the city. Intertwined with democracy and, by extension, intertwined with western civilization.

Borges, in his “Averroes’ Search,” part of his “El Aleph” anthology, portrays the Islamic philosopher as being unable to understand two words from Aristotle’s “Poetics” – “comedy” and “tragedy.” Despite being the foremost commentator on Aristotle in the Arab world, there was no way – as Borges points out – that Averroes could possibly understand the meaning of these two words, quite simply because comedy and tragedy lie beyond the boundaries of theocratic Islam, and of theocracy in general.

As is well known, fanatics have no sense of humor.

“ Just imagine if, of all the ancient writings, only the comedies of Aristophanes had survived. We would no doubt believe that Athens had been a society dominated by women, in which the only thing that men knew how to do was kill each other in war. All other things, the serious matters, were handled by women. ”

TAKIS THEODOROPOULOS is a novelist and a columnist for the Greek daily newspaper Kathimerini. His latest novel

“The Barefoot Cloud” deals with Aristophanes’ “The Clouds” and the discord between the great comic playwright

and Socrates in 5th century BC Athens. It has been published in French under the title “Le va-nu-pieds des nuages.”

His novel “The Spell of Dionysus” has been published in English (Academy of Athens Award, 1999).

Step off the beaten path this...

In 2006, inspired by a shared...

Step into a world of castles,...

In a land where the past...