Restoring Sacred Power to the Parthenon

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

From the book: "The Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures." Edited by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and the Melina Mercouri Foundation; Kapon Editions, Athens, 2003 (2nd Edition)

The Parthenon stood as a place of worship of the goddess Athena for 900 years before its conversion in the 6th century AD to a Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary – the Church of Parthenos Maria. It served as a church for nearly 1,000 years, becoming the fourth most important pilgrimage destination in the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire after Constantinople, Ephesus and Thessaloniki.

Since then, it has been a mosque, an armory, part of a fortified garrison and, now, a famous ruin. In a region that is so seismically active, it is a testament to the solid rock of the Acropolis and the material and quality of construction that the building itself remains standing after nearly two and a half millennia.

The present state of the monument is largely a consequence of human actions and interventions. In antiquity, while it was a still a place of cult worship for Athena, the most destructive event was the great fire of AD 267. The Heruli, a Germanic tribe from the north, sacked Athens and set the Parthenon ablaze, destroying the huge wooden beams of the roof and most of the inner facade of the cella.

During its conversion to a church in the early Christian period, the entrance on the east side of the building was blocked and reworked into a semicircular apse, the main entranceway placed at the western end. Marble structures on the long sides of the building, including six blocks of the sculpted frieze, were removed to make way for windows. Christian inscriptions were carved into the columns, icons were painted on the walls of the cella, and other decorative sculptures were removed, deemed inappropriate subject matter by the ruling clergy.

Under Latin rule, it became a Roman Catholic church of Our Lady, and a bell tower containing a spiral staircase was constructed in the southwest corner of the cella.

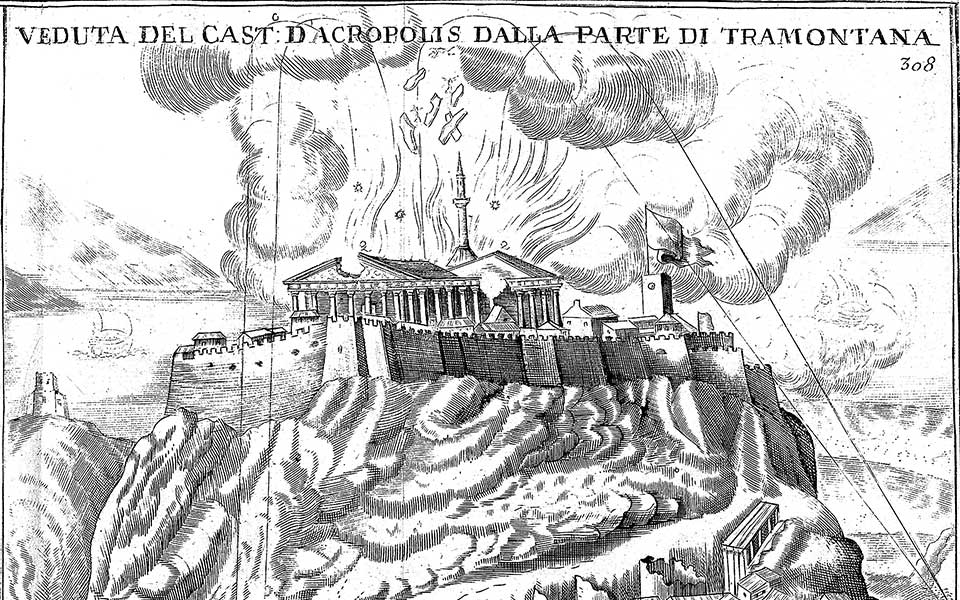

Acropolis Ablaze: The destruction of the Parthenon during the Venetian siege of Athens, September 1687. Contemporary Italian engraving.

© visualhellas.gr

Sometime before the end of the 15th century, during the Ottoman period, the Parthenon was converted into a mosque on the orders of Sultan Mehmed II. The Catholic bell tower was extended upwards and turned into a minaret and the Christian altar was removed. Iconography of Christian saints and martyrs were whitewashed, but many of the surviving sculptures from the pediments, metopes and frieze were left alone.

The Turkish explorer and travel writer Evliya Çelebi, visiting the site in 1667, was awestruck by the Parthenon’s beauty: “a work less of human hands than of heaven itself, it should remain standing for all time.”

During this time, a number of important studies were made on the sculptures, including sketches by the French artist Jacques Carrey in 1674. Carrey’s detailed drawings provide the most comprehensive evidence of the sculptures prior to the disastrous events that were soon to follow.

Portrait of Francesco Morosini as Doge of Venice, by Gregorio Lazzarini (1694).

Fragment of an exploded shell found on top of a wall in the Parthenon, thought to originate from the time of the Venetian siege in 1687.

By far the most extensive damage occurred on the night of September 26, 1687. During the Morean War (1684–1699), Venetian forces, under the command of Francesco Morosini, marched on Athens and besieged the Acropolis, then an Ottoman fortress. On that ill-fated night, a Venetian mortar shell fired from nearby Filopappos Hill struck the Parthenon and ignited the gunpowder that was being stored inside.

The sheer force of the explosion split the ancient temple in two, destroying the roof and central part of the building, and reduced the large sections of the cella walls to rubble. Three-fifths of the sculptures from the frieze and metopes crashed to the ground while 14 columns from the north and south peristyles collapsed. The explosion showered marble fragments over a wide area, destroying homes clustered around the slopes of the Acropolis, and killing nearly 300 people.

The building sustained more damage in those few catastrophic moments than in the previous 2,000 years.

In the aftermath, when the Venetians had overrun the citadel, Morosini, who would later go on to become the doge of Venice, looted the site of its larger surviving sculptures. He even attempted to remove the statues of Poseidon and Athena’s horses from the west pediment, but both were destroyed when the pulley system his soldiers were using snapped. Within a year, Morosini and his forces withdrew from Athens with the ignominious honor of having ushered in the latest phase of the Parthenon’s history: that of a famous ruin.

Painting of the ruins of the Parthenon and the Ottoman mosque built after 1715, by Pierre Peytier (early 1830s).

Over the following century, large marble fragments from the partially destroyed Parthenon were recycled as building material for the renovated Ottoman garrison. Surviving pieces of the decorative sculpture were illicitly sold to travelling Europeans, fascinated by the art and architecture of Classical Greece.

This Classical centrism cultivated in the consciousness of Western Europeans during the late 17th and 18th centuries, especially in Britain and France, was a double-edged sword. Not only did both nations see themselves as modern-day inheritors of ancient Greece and Rome, but the popularity of Classical literature among the educated classes, paintings and drawings of ruins and the early publications of antiquities by the nobleman-scholars of the Society of Dilettanti also sparked a rise in philhellenism which, in turn, aroused much sympathy and support for Greek independence.

Nevertheless, it opened up an insidious path to the wanton removal of antiquities to adorn personal collections and buildings at home, and the ruined Parthenon was the primary target.

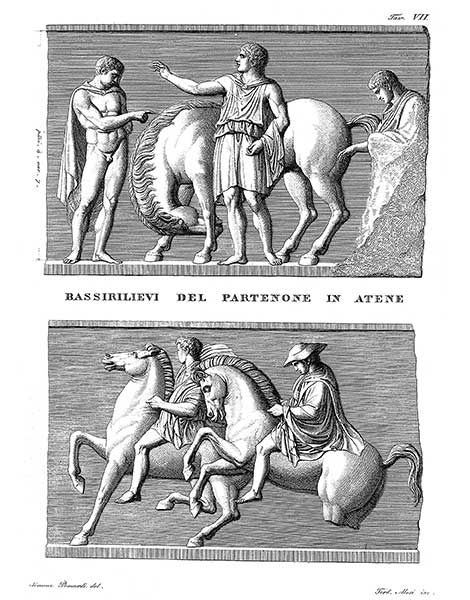

Studies in Ancient Art: Detailed drawings of sculptures from the Parthenon's west pediment by renowned archaeologist, painter and writer, Edward Dodwell (1767-1832).

© Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation Archives

Covetous Collector: Portrait of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, later in life.

© visualhellas.gr

In Ottoman-ruled Greece at the turn of the 19th century, the recently appointed British ambassador to the Sublime Porte of Constantinople (Istanbul) arrived in Athens with one thing on his mind: the Parthenon sculptures. That man was Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, a career diplomat with an insatiable appetite for Greek antiquities.

In his entourage, often overlooked in discussions about the removal of the Parthenon sculptures, was Lord Elgin’s personal chaplain and private secretary, the Reverend Philip Hunt, a wily negotiator and, like Elgin, a keen antiquarian. The third man was the Neapolitan court painter, Giovanni Battista Lusieri, employed to make casts and drawings of the sculptures.

From 1801 to 1804, Elgin and his associates not only stripped the sculptures from the Parthenon, they helped themselves to one whole Caryatid (sculpted female figure serving as a column) from the veranda-like porch of the Erechtheion, four slabs from the parapet frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike, and other pieces from the Propylaea. In all, Elgin oversaw the removal of more than half of the surviving sculptures from the Acropolis monuments, either hacked off or simply sawn into smaller pieces for ease of shipping, causing irreparable damage in the process.

What were his motives? And why dismember an already existing monument, albeit a ruin?

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

A guided journey across Athens’ storied...

Two centuries of dispute, diplomacy and...

Renewed negotiations, shifting public opinion and...