14 Stunning Rooftops in Athens for Food, Views...

From Michelin-starred tasting menus to sushi...

In the role of Leto, the actress Despoina Giannouli gazes out at the serene dignity of the Parliament building.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

“There was always music and joy in the Katakouzenos house. This was the salon of Athens, drawing together the painters, the poets, everyone in the world of the arts. Leto would play the piano. They danced; they sang. They didn’t just sit around and philosophize.” For Sophia Peloponnissiou, curator of the Angelos and Leto Katakouzenos House Museum and member of the board of the Katakouzenos Foundation, the singing is a meaningful detail; that illustrious circle that Greeks call the “Generation of the ’30s” filled mid-century Athens not just with culture, but with optimism: “They were people who had been through so much; they knew how to live.” There’s no better place to experience the magic of mid-century Athens than at the Katakouzenos House Museum. During that era, Greece was in the midst of a cultural renaissance, and Angelos and Leto were at the heart of it.

Angelos, a pioneering neurologist and psychiatrist deeply engaged in the arts, and Leto, an accomplished writer and pianist who spoke five languages with ease, shared a gift for forming meaningful connections with others. The rooms at the museum hold memories of wonderful evenings: the surrealist poet Andreas Embirikos reading his work, or the composer Manos Hadjidakis trying out a new piece for them on the Steinway, as he’d often do. On a given night, Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika might have been painting his magnificent “Four Seasons” on the two mahogany double doors (he lived with Angelos and Leto here for half a year, working in situ), William Faulkner might have stopped in for an informal session with Angelos, or Leto could have been deep in a tête-à-tête with Camus. It was an era of inspiration.

Ghika’s splendid doors define the intimate dining area.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

Ghika’s “Four Seasons” is a highlight among the many significant works in the Katakouzenos House Museum.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

Angelos and Leto at the Ancient Theater of Epidaurus. They enjoyed frequent cultural excursions with friends.

© Courtesy of the Angelos and Leto Katakouzenos Foundation

It was also an era of great friendships and idealism, a shared sense of purpose. Born, for the most part, during the first decade of the 20th century, the individuals who made up the Generation of the ’30s had, by mid-century, been through a lot together: the Balkan Wars, WWI and the National Schism, the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922 (when the millennia-old Greek-speaking community in Turkey was forced to flee the country), WWII and the occupation of Greece, and then the Greek Civil War. Of these, the catastrophic defeat in Asia Minor was perhaps the most pivotal event for the collective Greek psyche. The generation that created modern Greek culture takes its name from the decade following that catastrophe; amid their profound examination of Hellenic identity, a quest for “Greekness,” or “grécité,” took shape. This search would inspire a range of rich expressions in the arts throughout the decades to come, a unique cultural output that gave spiritual strength to the nation as Greece also emerged as a dynamic presence on the international scene.

Photographs and mementos fill the space with warmth.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

The Katakouzenos circle formed the generation’s core; Angelos was particularly close to two of the era’s most influential figures. The poet George Seferis – a 1963 Nobel Laureate – and Angelos had been friends since their university days in the 1920s in Paris, where they even lived in the same hotel. The painter Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika (“Nikolis” to those who knew him well) was with them in Paris, too; he and Angelos were close friends for over half a century.

Elias Venezis, a great friend to both Angelos and Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, would often join them. As much as anyone, Venezis embodied the Generation of the ’30s, both in his life and in his art; originally from Ayvalik in Asia Minor, he was taken prisoner by Turkish forces and assigned to a labor brigade during the conflict that ended so catastrophically for the Greek community in 1922. His books, including “Number 31328,” “Galini” (Tranquility) and “Aeolian Earth,” are uniquely moving documents of the war, of Asia Minor Hellenism, and of the refugee experience. George Katsimbalis (the “Colossus” that inspired Henry Miller’s famous travelogue “The Colossus of Maroussi”), and Tériade (Stratis Eleftheriadis of Lesvos, publisher of the seminal Parisian journal “Minotaure”) were also among their intimate friends. A younger generation could find inspiration in such company – as indeed did the writer Costas Taktsis (best known for “The Third Wedding,” his internationally well-received novel): “With Angelos and Leto,” Taktsis said, “I learned how to love.”

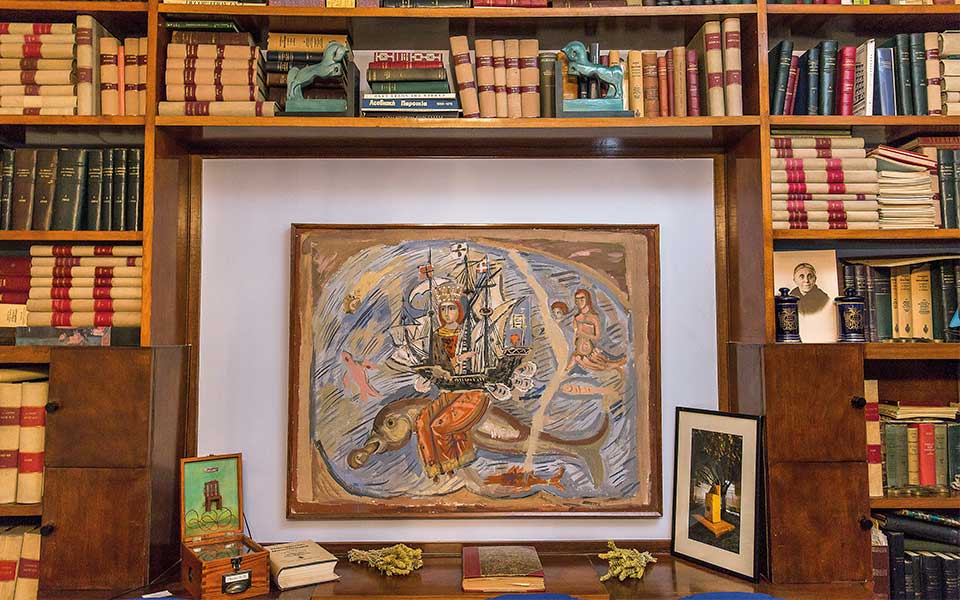

The “Mermaid Virgin” – copied (likely by Alex Mylona) from a post-Byzantine work in Lesvos’ Pervole Monastery – held profound significance for Angelos.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

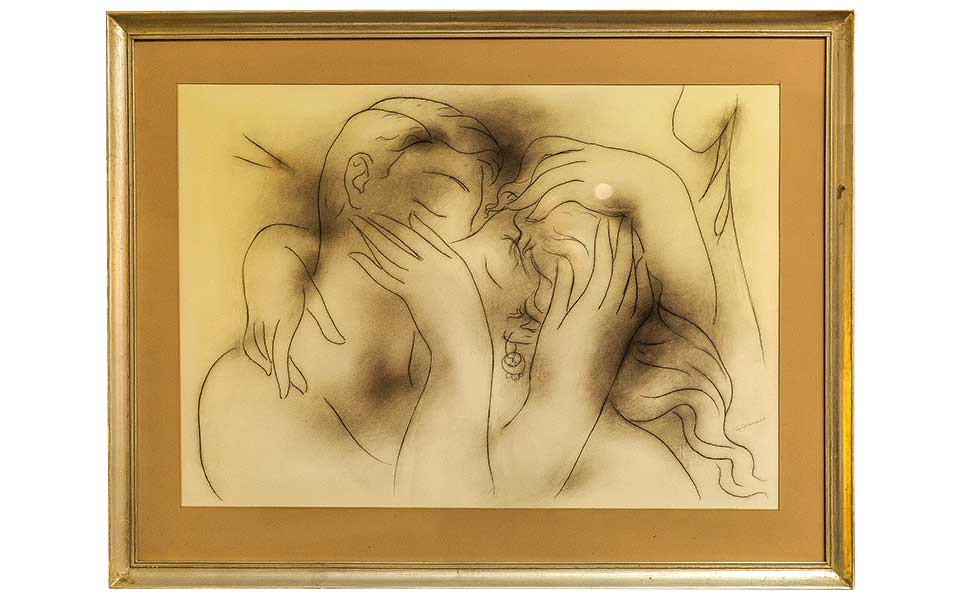

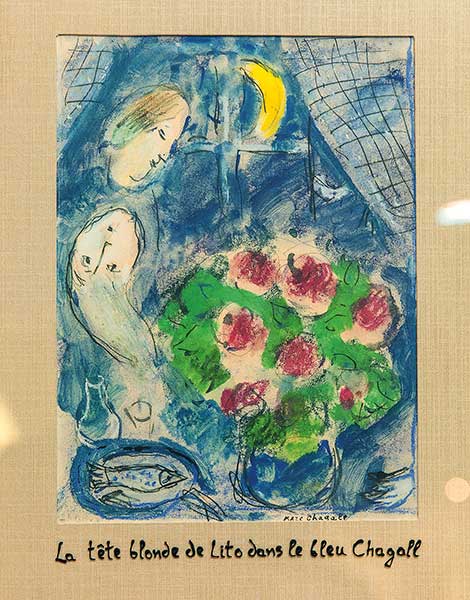

This is a small sampling of their close acquaintances – there’s scarcely a book on the heavily laden shelves that isn’t affectionately inscribed to Angelos or Leto. Many volumes of handwritten correspondence fill the rich archives, while photographs of their dear friends cover the tables. There’s art everywhere – all the more precious as each work was a gift from the artists. Besides Ghika’s splendid doors and several other works, there is Gounaropoulos’ series “The Kiss,” inspired perhaps by Angelos and Leto’s mutual adoration. These works hang in the large blue living room, where you can also see the portrait of Leto by Chagall, and two very fine pieces by the sculptor Tombros (one, delightfully named “Flirtation of the Bird and the Flower,” was created expressly for them). There are works by Theofilos, the profoundly influential folk painter of Lesvos, of whom Angelos was a great supporter.

The artist Yannis Tsarouchis, in addition to some fine paintings, left something more behind here; inspired by his work in the theater (which included creating the sets for “Norma,” the first opera production staged at the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, with Maria Callas in the title role), Tsarouchis created a delightful boudoir for Leto – it unfolds from the wall like a hidden stage. Towards the back of the house, a small salon with dark green walls holds stories of its own. “This room brings us to the 1930s,” says Peloponnissiou. “There was a similar room in their home at 7 Pindarou Street.” (That building was torn down in the 1960s, so they recreated their world in these grand rooms overlooking the National Gardens.) With its whimsical lamp and its velvet drapes done in salmon pink, that earlier space made an impression on the painter Spyros Vassiliou, who captured it with his signature charm. It was this painting – now hanging here – that inspired Peloponnissiou: “When I discovered those very same velvet drapes in a drawer, I decided to recreate that salon as it had once been,” referring to the room in the couple’s previous home.

The sofa in this room, a Josef Hoffmann piece, has its own story as well; snug, with high sides, it’s really more a loveseat, all the better for intimate conversation among three, with the guest of honor seated between Leto and Angelos. This sofa was a favorite of Seferis, Camus, Elytis and Faulkner. Peloponnissiou light-heartedly dubbed it “the sofa of the Nobels”.

A work from Gounaropoulos’ dreamy series “The Kiss,” dedicated to Angelos and Leto.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

“The Blond Head of Leto in the Blue of Chagall” is a favorite of many visitors.

In the Green Room, a portrait of Leto by French Ambassador Jean Gustave Adolphe Baelen.

© Dimitrsi Vlaikos

Many international figures, Nobel winners and others, joined their circles from time to time; with Angelos’ post as president of the Greek-French Cultural Union and his Paris education, and Leto’s easy, multilingual warmth, the couple were excellent cultural ambassadors. Angelos and Camus had met in France; Angelos invited him to speak about the future of European civilization. With Leto, Camus found an immediate intellectual rapport, which she made the subject of her book “In the Company of Albert Camus.” Faulkner would later call his evening here one of “the most fascinating of his life.” He also sent a photo of himself, dedicated to “the face Marlowe wrote about,” a nod to Christopher Marlowe’s famous reference to Helen of Troy as “the face that launched a thousand ships.” Leto had clearly made quite an impression. Leto also made quite an impression on Peloponnissiou, who knew her well. Their friendship began in 1989, when she read Leto’s book “Angelos Katakouzenos: My Valis,” a tribute to her husband. Peloponnissiou, moved, wrote her a letter. Leto replied with an invitation, by telegram. So began what the curator describes as the most inspiring friendship of her life.

When Leto died in 1997, Peloponnissiou was surprised to find herself entrusted with a foundation. The house looks today as though nothing has been touched from the days of Angelos and Leto. In reality, the restoration and the archiving were monumental tasks; Peloponnissiou involved her whole family – even her little daughter, who was three at the time. It was and is a labor of love; Peloponnissiou has always been, and still is, a volunteer, devoted to preserving a magnificent cultural legacy. What’s more, she has ensured that these inspiring rooms retain their original sense of purpose; while preserving the memories and works of a significant era, the Katakouzenos House Museum remains a place for culture. A full calendar of exhibitions, talks, recitals, performances and other events keeps the house filled with music and joy. “People tell me,” the curator says, “that events here have a special quality, something intimate, something that touches the heart.” Angelos and Leto would be pleased.

From Michelin-starred tasting menus to sushi...

We join archaeologist and MONUMENTA coordinator...

Amid neoclassical homes and narrow streets,...

Beyond souvlaki lies a carnivore’s paradise,...