Neoclassical Architecture: From Greece to the World

Discover how ancient Greek architecture inspired...

A still from Jules Dassin’s film “Phaedra,” starring Melina Mercouri, from a scene shot on the Acropolis.

© F.PAGES / PARIS MATCH VIA GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

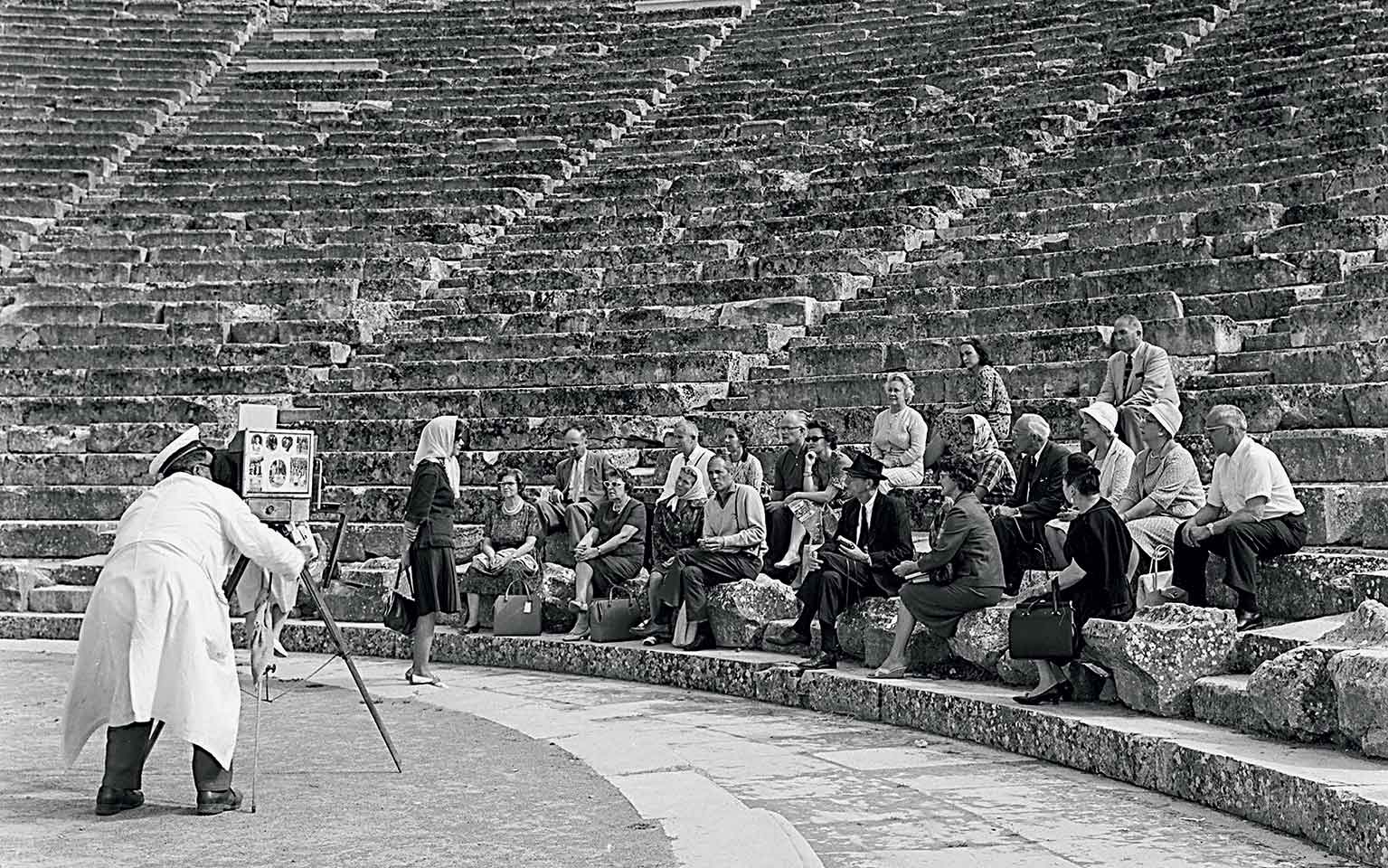

They traveled to Epidaurus on one of those old buses. “It was a Saturday and the performance began on time. Shortly after, however, it started to rain, so it was postponed. We spent the night in cars and the following day watched the performance without a problem.”

This is an account from Mary Ioakeimoglou, then a young employee at the Greek National Tourism Organization (GNTO), of how in the summer of 1960 she traveled from Athens to Epidaurus – back then it was a real journey, not the two hours at the most that it takes today – to see Maria Callas in the title role of Bellini’s “Norma,” the ultimate diva’s first appearance at the ancient theater.

As I read “Journey in Time,” a book by Kostas Katsigiannis on the history of the GNTO and Greek tourism, I couldn’t help wondering how Mary’s 1960 experience would play out in the summer of 2020. Computer, social media and mobile networks would no doubt be buzzing with outrage, along with demands for compensation.

Tourists snapping photos of a woman in traditional garb, on the island of Corfu.

© SERGE DE SAZO VIA GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

With hindsight, one might be tempted to say that, for one day at least, Epidaurus must have resembled a campsite or Woodstock-like gathering for the performing arts – although that American rock music festival wouldn’t take place until nine years later – capturing, to some extent, the innocence of the decade from 1955 to 1965, which now is justifiably referred to as the “golden age” of Greek tourism.

In the mid-20th century, Greece started welcoming the first recreational visitors, who swam in pristine seas and discovered on the mainland not only an ancient civilization but also a people with customs and traditions which, compared to their own, were very different, even exotic. It was then that the term “touring” was phased out by the relevant authorities and irrevocably replaced by the word “tourism.” One of the first slogans, simple but clever, to target foreign visitors was “Going to Greece is like coming home,” which was launched in the 1930s.

Tea for two with an amazing view of the Temple of Zeus, at the Royal Olympic Athens Hotel, 1969.

© DIMITRIS HARISSIADIS 7 BENAKI MUSEUM PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES (ΦΑ. 12_X69.66-11)

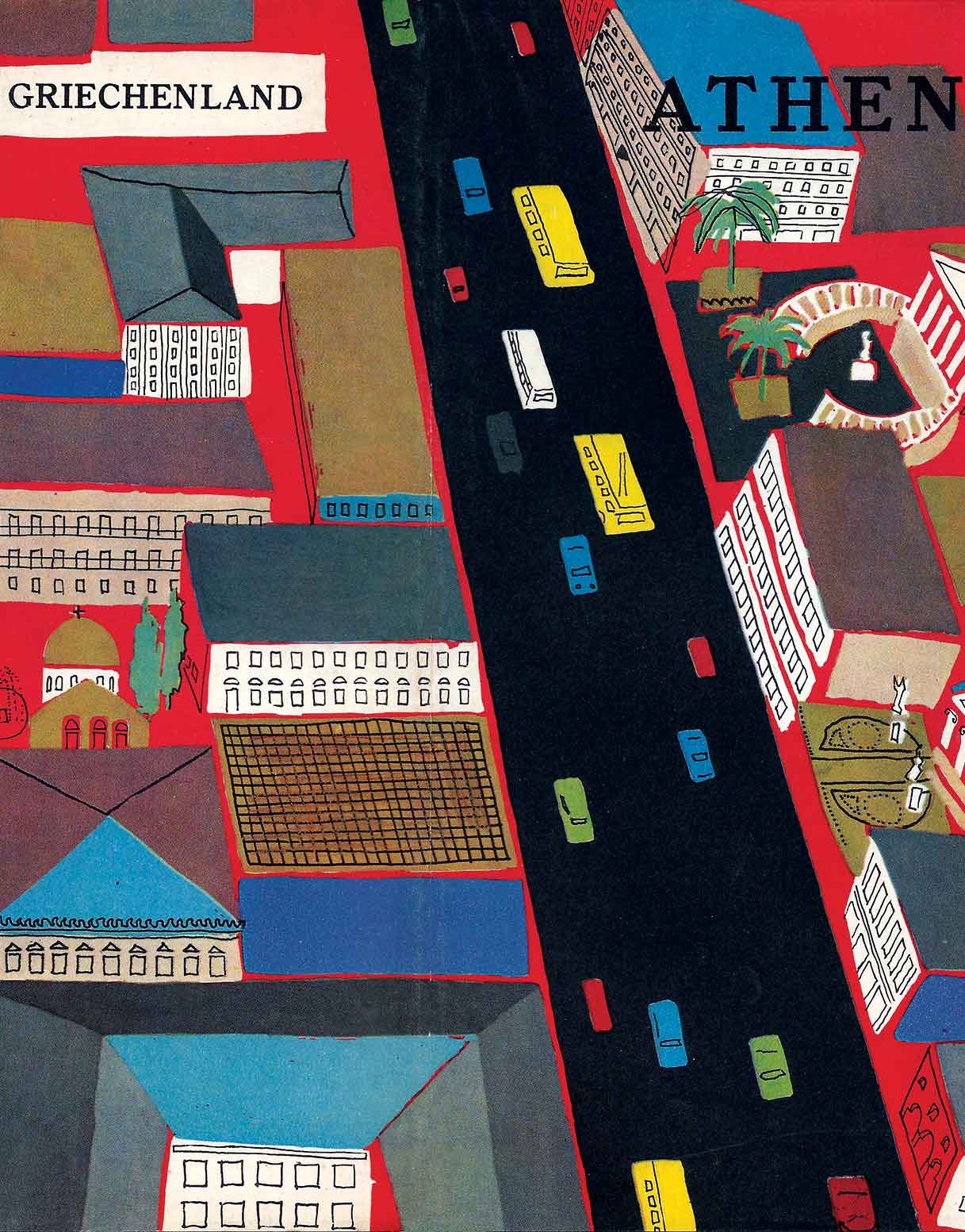

GNTO Poster, 1962.

© GNTO

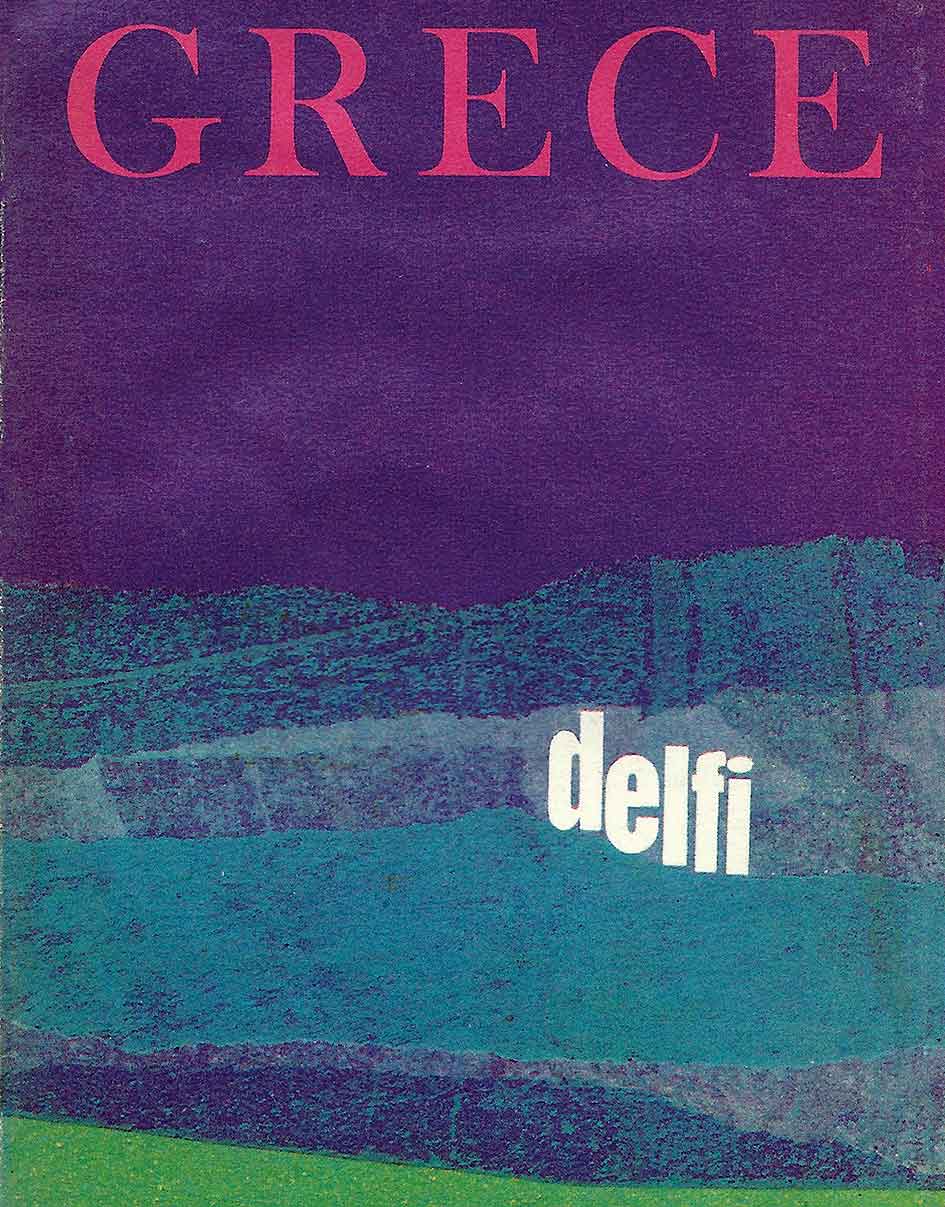

GNTO Poster, 1967.

© GNTO

As the number of visitors constantly increased, so, too, did the great changes and transformations in Greek tourism. The 71,000 arrivals in 1930 rose to 200,000 in 1955, 400,000 in 1960, while in 2018 the country attracted some 33 million visitors.

But let’s go back to the golden decade, before the appearance of jet skis, when celebrated graphic designers Freddie Carabott and Michalis Katzourakis created posters for the GNTO, Anthony Quinn danced on the beach in “Zorba the Greek” and Sophia Loren gave eternal fame to the island of Hydra with the film “Boy on a Dolphin.”

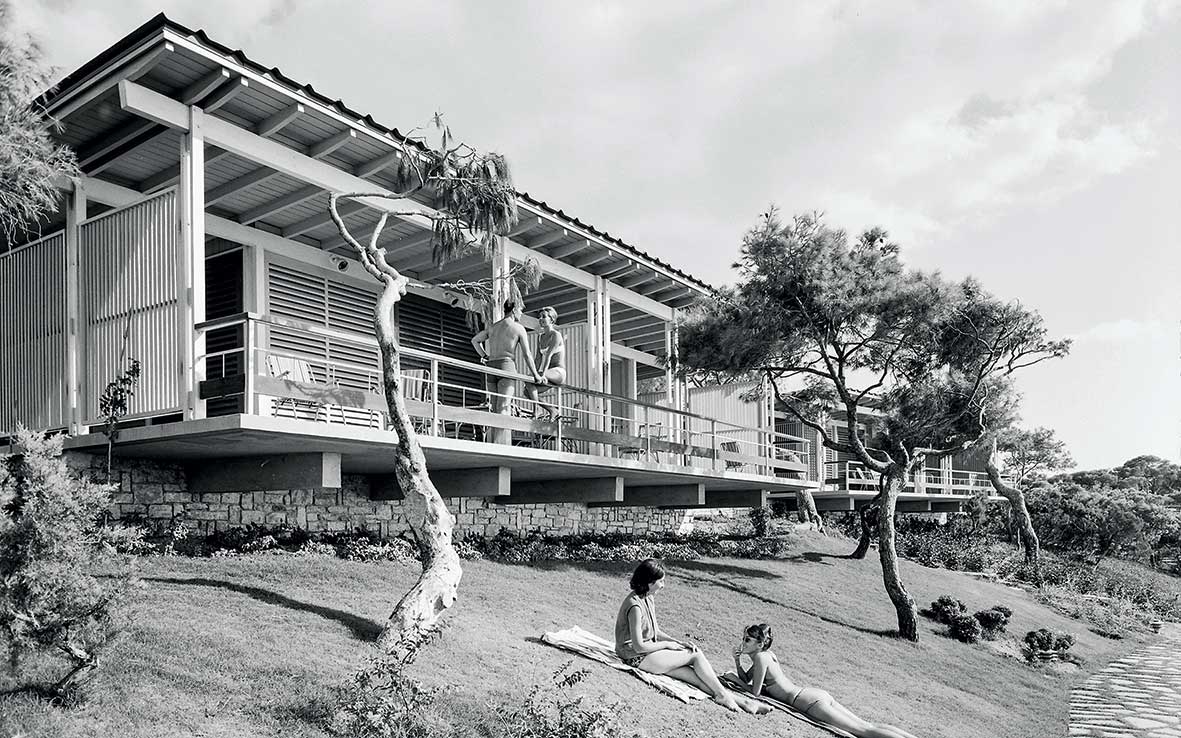

The jewel of the Athenian Riviera: Astir Beach, 1961.

© DIMITRIS HARISSANIDIS / BENAKI MUSEUM PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES (ΦΑ. 12_AT.152-5)

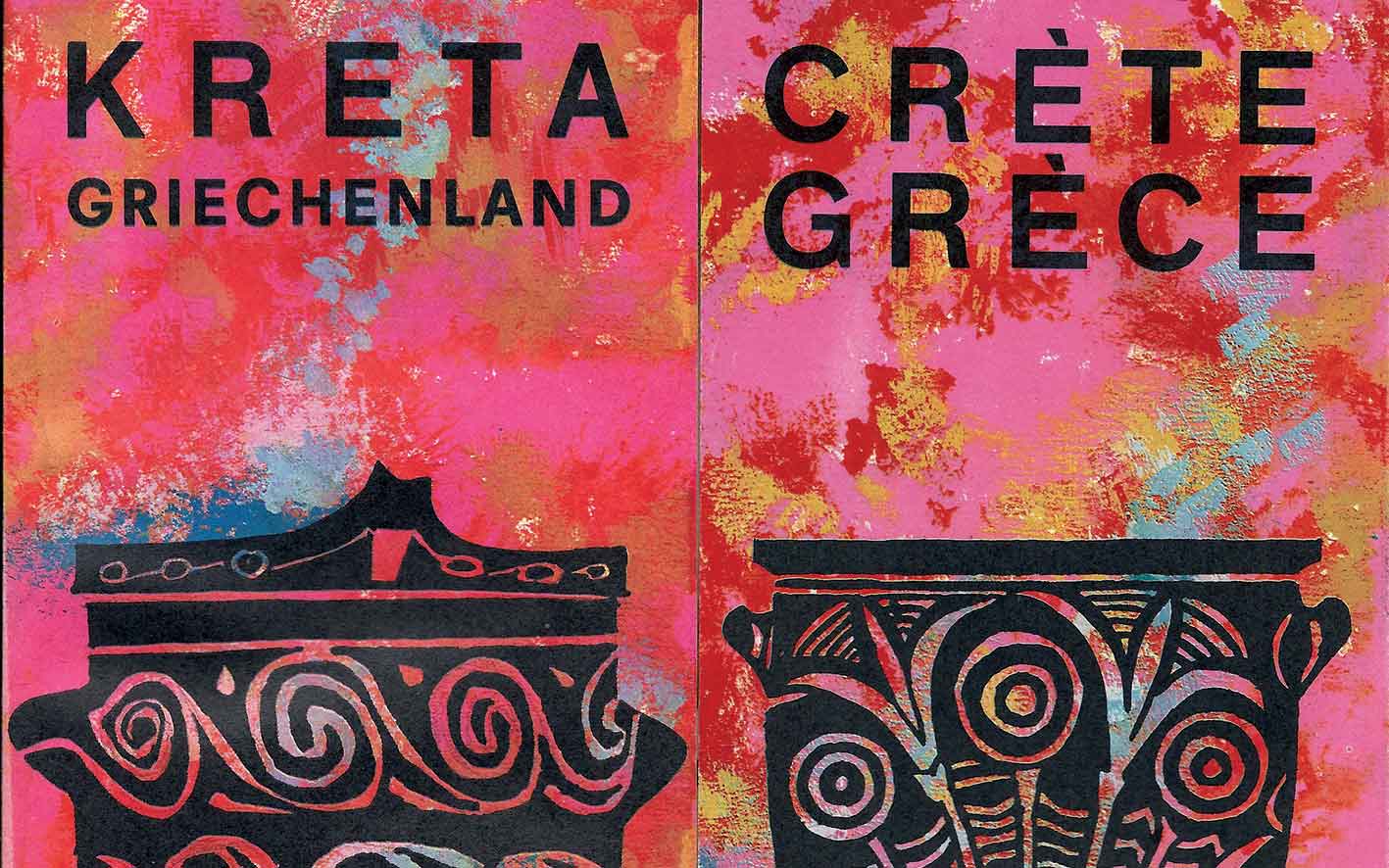

GNTO Poster, 1964.

© GNTO

Xenia Nafplio was designed by the architect Ioannis Triantafilidis and welcomed its first guests in 1961.

© DIMITRIS HARISSANIDIS / BENAKI MUSEUM PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES (ΦΑ. 12_AT.137-2)

Greece had left behind a turbulent past marked by war and conflict. In the minds of many Europeans and Americans, it was a country striving to get back on its feet, endowed with great natural beauty and a rich cultural heritage but little else.

In the early 1950s, the first concerted efforts were made in the tourism sector, including the re-establishment of the GNTO, the state agency that laid the foundations for attracting mass tourism; the know-how the GNTO acquired in these years would be later exploited by the private sector, which further developed the concept of Greek hospitality.

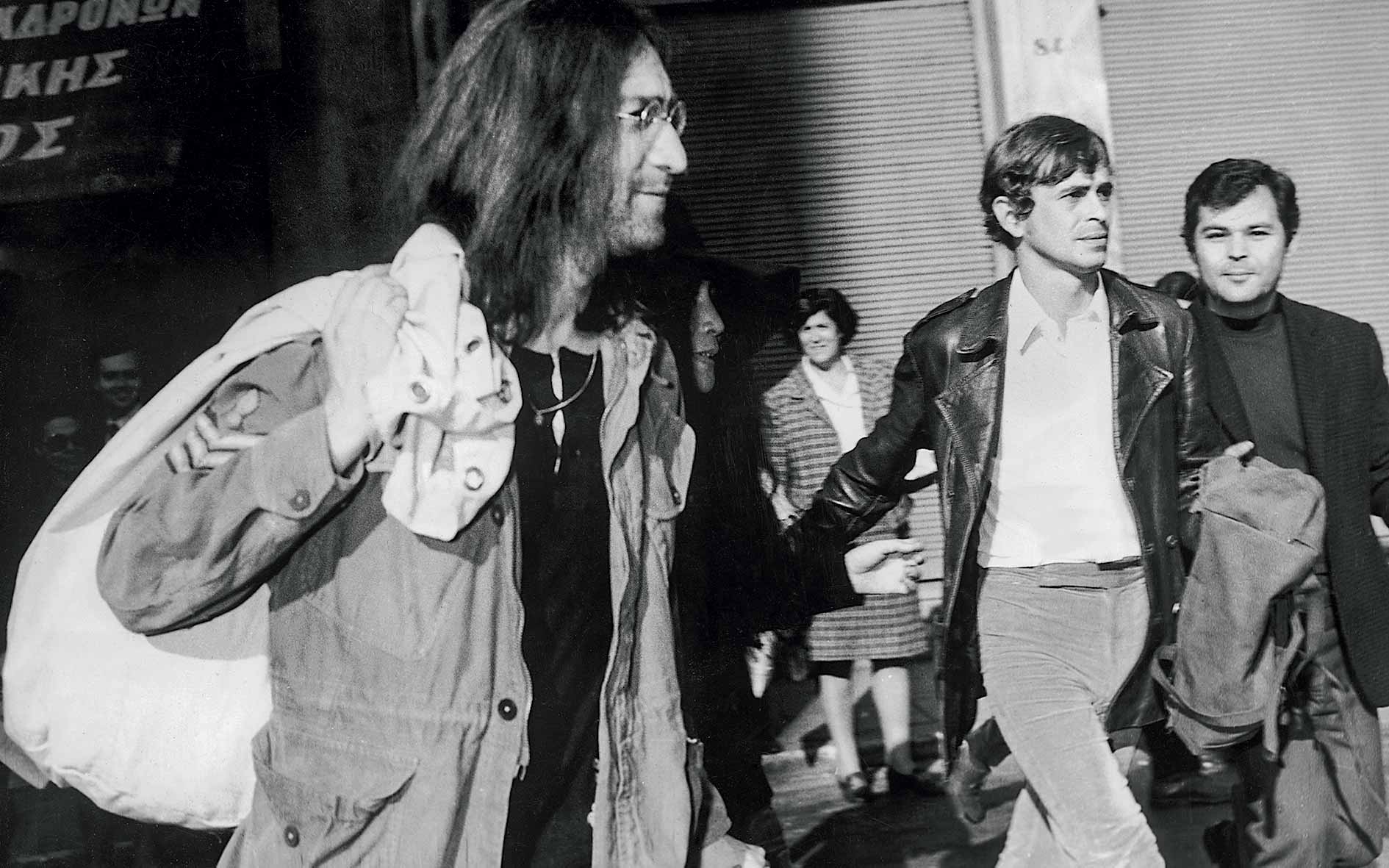

John Lennon and Yoko Ono in Athens, November 20, 1969.

© KEYSTONE / GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

A group of visitors posing for a souvenir photo at the Ancient Theater of Epidaurus, 1963.

© DIMITRIS HARISSANIDIS / BENAKI MUSEUM PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES (ΦΑ 12_X69.66-11)

In 1951, the GNTO initiated an ambitious program to construct hotel facilities throughout the country. At ancient Epidaurus, Delphi and on Mykonos, as well as at other sites, the hotels were the work of the modernist architect Aris Konstantinidis. The hotels built under this program were called the Xenia (this designation became increasingly associated with those hotels designed by the team under Konstantinidis).

These were constructions that took full advantage of their locations while remaining sensitive to the natural landscape, and were built with an emphasis on the simplicity and purity of form. This unprecedented – by Greek standards – project resulted in a series of hotels designed with a uniform architectural concept, prompting the Ministry of Culture to later designate some – including the Xenia of Igoumenitsa, Platamonas, Kalabaka, Paliouri, Vytina and Sparta – as “monuments.”

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy on the Acropolis, June 12, 1961.

© BETTMANN / GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

One of the Paris Opera dancers jumps from a boat off the coast of Epidaurus, 1965.

© J. GAROFALO / PARIS MATCH VIA GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

Great Greek and foreign artists appeared for the first time at newly inaugurated music and theater festivals, and there was a rare mood of optimism in the air. Callas was packing them in, as was Dimitri Mitropoulos with the New York Philharmonic.

A little later, Herbert von Karajan and the legendary team of Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn would bring further glamour and international recognition to the Athens Festival. Construction of the Hilton Athens began in the heart of the city, and work on Astir Vouliagmeni Beach carried on apace.

As the 1960s unfolded, Greece hosted its first International Exhibition (Biennale) of Sculpture, and the Hotel Mont Parnes opened its doors on Mt Parnitha. Romy Schneider and Alain Delon watched Katina Paxinou perform at Epidaurus.

In the 1970s, Greece continued to be a magnet for the international jet set, welcoming visitors such as Ingrid Bergman, Audrey Hepburn, Raquel Welch, Warren Beatty, Sir Laurence Olivier and Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Marlon Brando and Jules Dassin on the Acropolis, 1958.

© KEYSTONE / GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

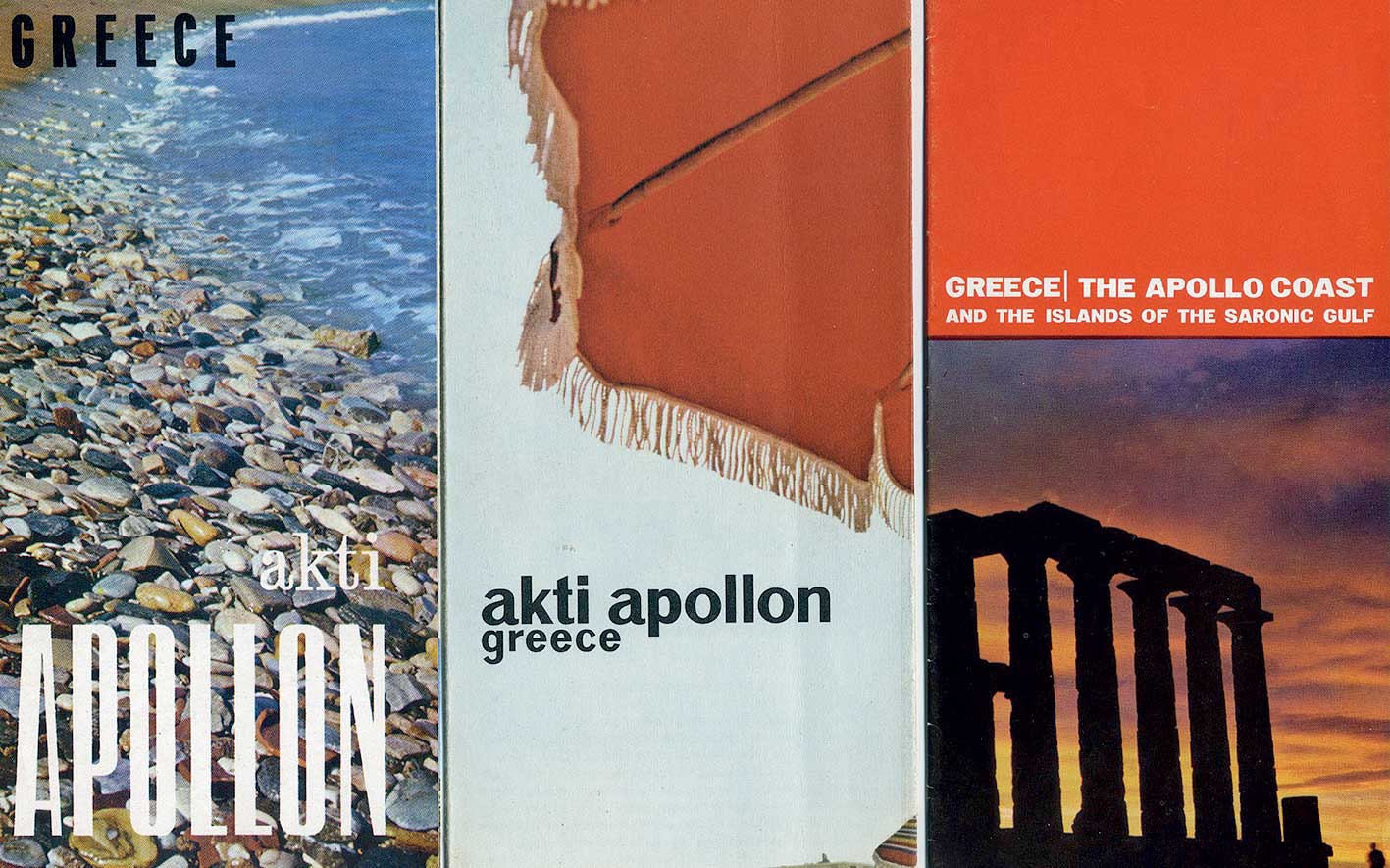

The GNTO posters and photographs of the time were works of art by celebrated creators. Before World War II, the first snap for the first poster promoting Greek tourism featured a shot of the Parthenon by the acclaimed Greek photographer Nelly’s. In the years that followed, Greek tourism posters would alternate between blazing works of color, abstract pieces, and creations of geometric minimalism – works by great painters and artists including Spyros Vasiliou, Panayiotis Tetsis, Michalis Katzourakis, Alekos Fassianos and even the pioneering sculptor Takis.

GNTO poster

© GNTO

Marianne Ihlen, with her son Axel Jensen Jr. on her lap, at a table with (L-R) Leonard Cohen, an unknown male friend, and the couple George Johnston and Charmain Clift, Australian authors. Hydra, 1960.

© JAMES BURKE / LIFE VIA GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

With so much going on, one or two amusing blunders were inevitable. One such instance, mentioned in Katsigiannis’ book, occurred in 1972 when a GNTO brochure informed foreign tourists about the Afandou Golf Course on Rhodes. Absolutely thrilled, one American golfer traveled with his clubs all the way from New York to Rhodes only to discover that the course was still under construction.

Aristotle Onassis takes Sir Winston Churchill for a drive, 1959.

© STAVROS GEORGALLIDIS PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES

GNTO Poster, 1963.

© GNTO

An advertisement for Olympic Airways, 1966.

© GNTO

Such slips aside, the mood at the time is aptly reflected by the proposal for a GNTO advertising initiative that began in 1959. The British specialist Richard Stubbs, asked to design the program for the 1959-1960 season, noted in his proposal, among other things, that the advertising campaign should present Greece “as an exclusive country, as a holiday ‘Eldorado,’ far off the usual tourist itineraries, and as a country for persons of wealth and refined taste.”

This was the time when ouzo began to acquire ardent fans, the greeting “kalimera” became known internationally and “horiatiki” salad became synonymous with Greek cuisine. In short, it was the era when the world met Greece and they became friends.

This article was originally published in the print magazine Greece Is Philoxenia 2019-2020. To browse or download a digital copy of the magazine click here. Hard copies can also be ordered from anywhere in the world via our e-shop at only the cost of postage and packaging.

Discover how ancient Greek architecture inspired...

Before passports and package tours, pilgrims...

In Syntagma Square, marble, flame, and...

Discoveries along Amalias Avenue, from the...