Every Corner Tells a Story: The Old Town...

Without noise or concrete, the Old...

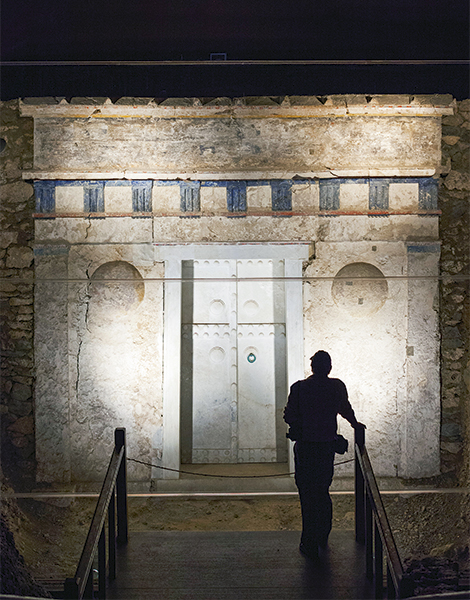

The archaeological site of Aigai.

© aigai.gr

Why is ancient Macedonia still important today? Where was it located exactly, who were the Macedonians, and who really were Philip II and Alexander? The first book in a new series by De Gruyter, a German publishing house, entitled “Ancient Macedonia” and co-written by Miltiades Hatzopoulos, historian, academic and writer, offers answers to all of these questions. It is a critical evaluation of studies from past decades on Macedonia, a convincing approach on the development of historical research regarding this civilization. This was an unexplored landscape until the early 1950s, before the unprecedented and extraordinary archaeological findings discovered in Vergina, Pella, and Dion, to mention a few.

Why does Macedonia still interest us to this day?

Because it was the precursor to the nation state, the herald of modern European monarchies, whose direct descendants are contemporary democracies. This model passes from Macedonia to Rome, is in turn rediscovered by legislators towards the end of the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance, while it also seals the creation of modern European states.

Ancient Macedonia is exciting because it is a combination of archaism and modernity, a preservation of Homeric values and a thirst for the most recent spiritual wonderings and cultural creations. Macedonian elites would invite poets, historians, philosophers, architects and painters from Athens, but they did not copy – instead, they created new artistic and intellectuals schools.

The combination of architectural orders, the painting of illusions, the differentiation between structural and decorative elements in monumental buildings, the use of roughcasts in wall painting; all these were developed for the first time in Macedonia, before being spread throughout the Hellenistic world, to later be copied by the Romans. The vaulted tombs with monumental facades, the huge luxury domes, the royal palaces – these are all Macedonian innovations.

The Macedonian version of the Attic dialect, the “common language” of Greece, a direct predecessor of modern Greek, quickly spread throughout the ancient world. In fact, Philip II (and even Arhelaos before him) had adopted the Attic dialect as the formal language of Macedonia, instead of the Macedonian dialect. Ashoka, the Indian reformer emperor who introduced Buddhism, wrote his decrees in common Greek as well. We know that Christianity was spread in Greek, too. We knew all of this. What we did not know was how the composition of these elements occurred in ancient Macedonia, not beyond its lands.

The facade of the so-called “Tomb of the Prince” at Vergina. It had double, marble doors, blue capitals and two shields rendered in plaster relief.

The golden larnax bearing the Macedonian star, in which were placed the remains of Philip II; made of 24 carat gold, weighs 11 kg.

© Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai-Vergina

Where was ancient Macedonia located?

With the expansion of the Macedonians, the borders of Macedonia also changed. The ancient kingdom, in classical times, extended from Pindos to the Stymonas valley, and from Ossa to Kamvounia, until just north of today’s Greek border. It was divided into two parts under the Romans: Macedonia Prima (in the South), and Macedonia Secunda (in the North). Soon the Province of Macedonia was founded, which included all the Balkans, while during the Byzantine era it is limited to the Theme of Macedonia, in Thrace.

In essence, ancient Macedonia is but a memory, empty of any administrative or political content. It vanishes from the map under the Ottomans, who created administrative areas that had no historical basis. In later years geographers attempted to connect ancient names with contemporary times; such is the case with Macedonia. On the cusp of ancient and modern Hellenism, it was subject to foreign invasions and population resettling, and as such many names were lost. Instead, names such as Olympus, Veria, Saloniki survived. But Edessa – known as Vodena, a Slavic name – shows the difficulties present in connecting archaeological spaces with ancient towns or city names.

Towards the end of the 19th century, with the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, European diplomats included three Ottoman vilayets – Thessaloniki, Monastiri, Skopje – into one single unit called Macedonia. This Macedonia that has no historical basis was then divided into three during the Balkan Wars – the Greeks, who got the biggest part, the Serbs and Bulgarians.

The limited historical sources and archaeological findings open to a variety of interpretations left things open to all sorts of disputes, challenges and differing opinions. Matters were cleared somewhat with the connection between Aigiai and Vergina, the birthplace of the Macedonian kingdom. In this book I follow these annexations and finish with the lands that Macedonia included during the end of the classical era.

Who were the Macedonians?

They were a pastoral people, stock farmers who lived in the highlands of Mount Olympus, Kamvouni and Pieria. In the 7th century BC they moved to the coastal plains, pushing out or eliminating the natives, few of which remained in the area. They then founded the city of Aigiai and began to expand. Anyone who was assimilated via the army, or via education (the gymnasiums) were given Macedonian citizenship.

The Macedonian community is strengthened by the assimilated locals, foreign missionaries and migrants from other Greek areas. They do not write in the Macedonian language, but after the 5th century BC in Athens. They worship the same gods as all the other Greeks, organize the same ceremonies to mark the transition from one age to the next, they have the same glorification of death, and life after death. They share the same political operations, municipality, church, parliaments, masters – it is not a unique kingdom. Macedonian cities boasted wonderful public buildings such as buildings, theaters, temples and stadiums.

Miltiades Hatzopoulos, historian, academic and writer.

Do we learn anything new about Philip, Alexander and their relationship?

An in-depth research into the genealogy of sources, most dated 300 – 50 years later and not always objective, are often rather scandalous and brought to light some interesting information. Philip II had seven wives, but one after the other; he did not have a harem, and he did not seem to have children with more than one woman at the same time. Philip’s former wives would retire to some part of the palace; for instance, Olympiada, the longest lasting of his wives, when he married his last wife, Cleopatra.

The rumors circulating since antiquity state that Alexander was an accomplice in the murder of his father. Descriptions of the murder scene portray a surprised Alexander who feared for his life as he is taken from the theater to the palace. Moreover, the grave that Andronikos discovered – which I believe is Philip II’s and not his son’s, Philip III – the frieze depicts a scene that shows their good relationship: Philip II killing a lion and Alexander, in the centre of the composition, rushing to help him.

Was Alexander a romantic who wanted to conquer the world, or a pragmatic politician?

He inherited a war from his father, and he dealt with things as they came, depending on the circumstances. When Alexander was in Persepolis in 330, he thought about returning back to Macedonia, either by himself or with part of his troops. Yet the murder of Darius and the continuation of hostility from his countrymen forced him to keep moving, and to reach the Indus. Yet this was not his original goal.

I finish the book by paying attention to the sources. Many spoke badly of the Macedonians. Polybius, the biggest historian of the Hellenistic era, did not tell the whole truth when the interests of his compatriots from Achaia and protectors of the Romans were concerned.

This article was previously published in Greek at kathimerini.gr.

Without noise or concrete, the Old...

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

A compact archaeological guide to the...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...