The Secret Life of the Odeon of Herodes...

A monument of memory and music,...

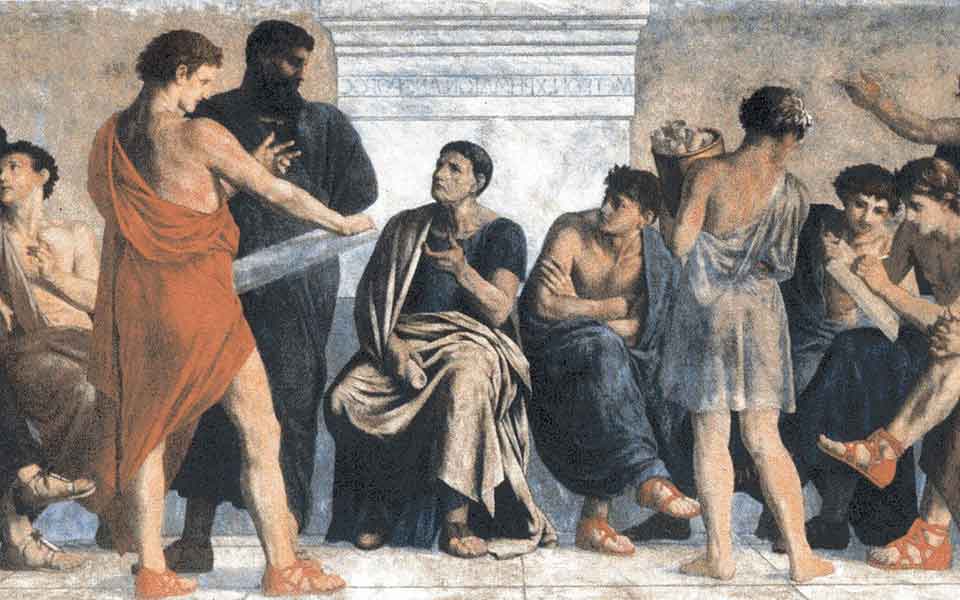

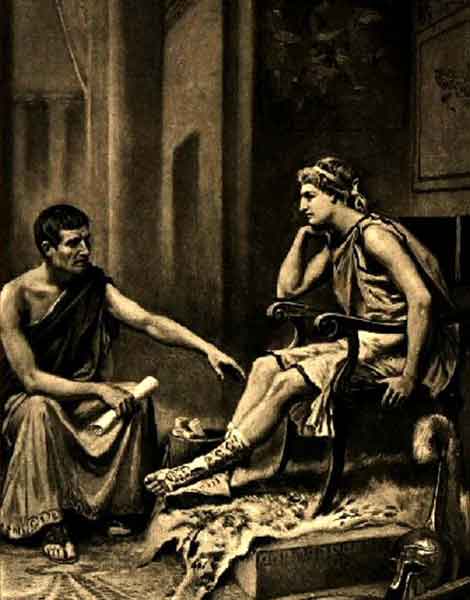

"The School of Aristotle," by Gustav Adolph Spangenberg (c. 1883-1888). Access to education in ancient Greece was, for the most part, the exclusive preserve of young males from wealthy backgrounds.

© Public domain

The education system in ancient Greece was regarded as a foundational pillar of society, preparing individuals for responsible citizenship. Renowned for its emphasis on holistic development, physical fitness, and moral virtues, this approach has left an enduring legacy on teaching practices in many parts of the world today.

In general, the ancient Greeks valued education for its role in cultivating well-rounded citizens, and, certainly in the case of Athens, promoting critical thinking and preparing individuals for active participation in the governance of the polis (city-state). From the outset, however, it’s important to note that the sources we have are heavily skewed towards Athens and Sparta, with precious little information on the hundreds of other city-states during the Classical period of the 5th and 4th centuries BC. In fact, scholars estimate anywhere between 1,000 and 1,500 city-states existed in mainland Greece and the wider Greek world during this time, each with their own unique characteristics and traditions. Like most aspects of life in ancient Greece, we’re only seeing a very small piece of the puzzle.

That said, we’ve got a good idea of how things worked in Athens and Sparta – two very different city-states that, for the most part, were diametrically opposed to each other in just about every conceivable way. We also know that access to a formal education, whether through a private tutor or the attendance of a state-funded school (e.g., the infamous “Agoge” in Sparta), was entirely dependent on gender and social status. It was very much the domain of the privileged few, namely males from the upper and middle classes, i.e., the sons of wealthy, free-born citizens, excluding slaves, metics (Greek and non-Greek immigrants), and, in the case of Athens at least, women.

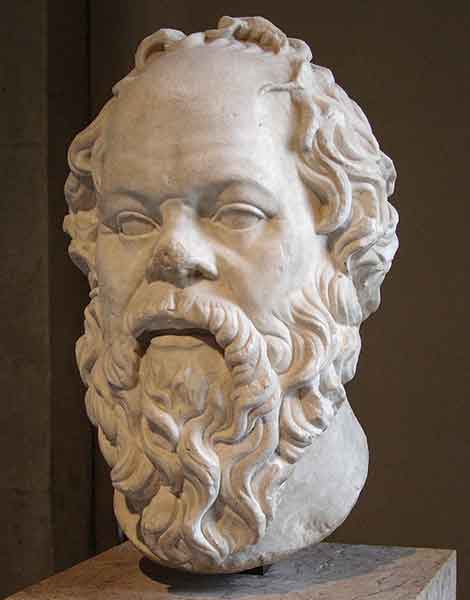

Socrates (c. 470-399 BC), the founder of Western philosophy, was the progenitor of the so-called “Socratic method,” characterized by questioning and dialogue.

© Public domain

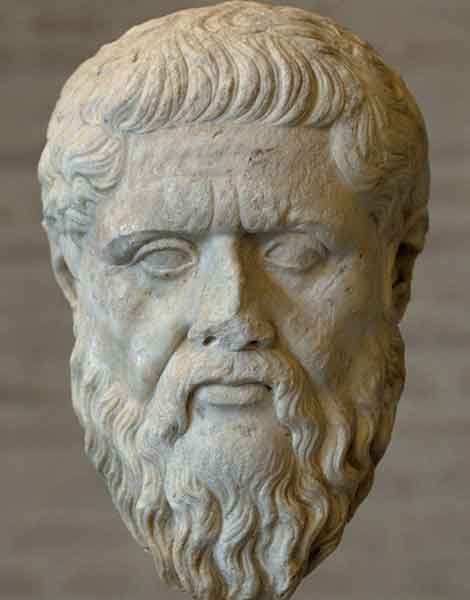

Plato (428-348 BC), who was taught by Socrates in the last years of the 5th century BC, founded the famous Platonic Academy in Athens in 387 BC.

© Public domain

Education in ancient Greece had its roots in the Homeric era, c. 8th century BC, where a rudimentary form of schooling, which emphasized the value of competition and heroic exploit, was imparted to young boys by their fathers or guardians. However, it was in the Classical period that the education system underwent a transformation. In Athens, this era witnessed the emergence of renowned philosophers and educators such as Socrates (c. 470-399 BC), Plato (428-348 BC), and Aristotle (384-322 BC), whose ideas profoundly influenced the educational landscape.

The philosophical foundation of ancient Greek education was multifaceted. One of the most influential philosophical tenets was the belief in the holistic development of the “kalos k’agathos,” the “wise and good” man. This concept stressed the importance of nurturing both the mind and the body, producing well-informed, ethical, and engaged members of the polis.

Painting of an idealized reconstruction of the Acropolis and Areios Pagos in Athens, by Leo von Klenze (1846).

© Public domain

The curriculum of ancient Greek education evolved over time but maintained a focus on the holistic development of individuals. Like today, formal education was conducted in two main stages: primary and secondary (or higher).

Primary education (“paideia” – literally “learning”), which in Athens was typically conducted in the home by private tutors, focused on basic literacy and numeracy skills. From the age of six or seven, boys were taught to read, write, and perform simple arithmetic, as well as music, history, and ethics. Physical education was also emphasized to nurture their physical prowess and instill discipline – especially important in the militaristic state of Sparta. Girls in Athens, on the other hand, were limited to learning the art of household management, which included weaving and other skills deemed essential for their future roles as wives and mothers.

Primary education for boys typically ended between the ages of 14 and 16. Some progressed on to secondary or higher education, known as “ephebeia,” which lasted until the age of eighteen, when they entered the “ephebos” social class and began military service. During this secondary stage, the curriculum expanded to include subjects such as philosophy, rhetoric, and advanced mathematics. For those who could afford it, families paid for their sons to receive private tuition from a Sophist, a member of a class of itinerant teachers and intellectuals who specialized in dialectics and rhetoric. Students also continued to engage in comprehensive physical training at the “gymnasium,” preparing them for their roles as citizen-soldiers in the polis. In Greece today, secondary school education is still referred to as “gymnasio.”

The curriculum was not standardized across Greece but varied based on the city-state and the preferences of individual families. Rhetoric held particular significance in Athens, as it equipped individuals with the persuasive skills necessary for public speaking and participation in the Athenian Assembly, which was made up of 4,000 citizens. Sparta, on the other hand, prioritized military training and physical fitness.

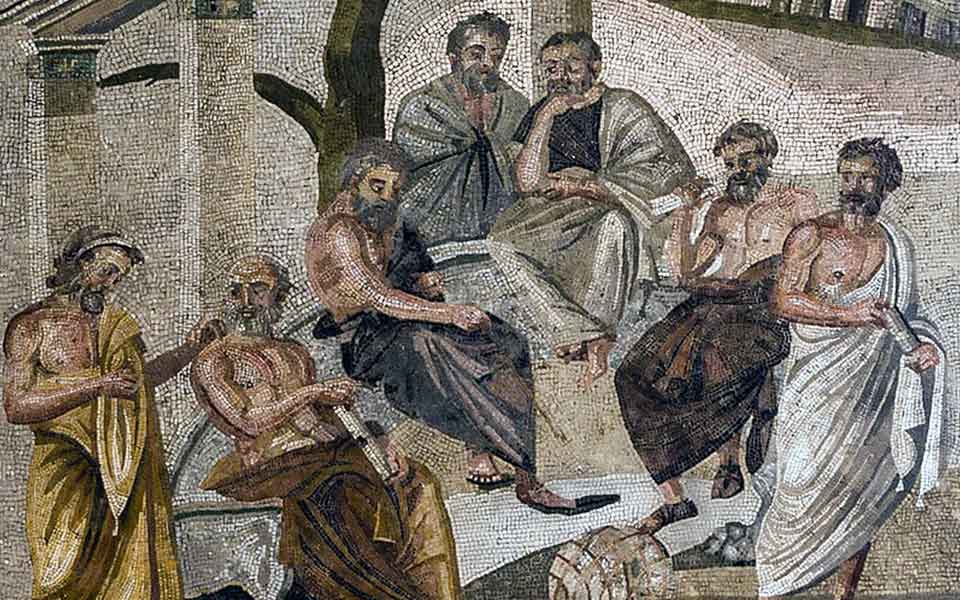

Plato's Academy mosaic in the villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii, around 100 BC to 100 AD.

© Public domain

While education was intended to cultivate virtuous citizens, it also had its limitations. As mentioned, slaves and women were largely excluded from formal education, highlighting the societal hierarchies and gender disparities of the time. On the whole, upper-class women in Athens were expected to stay at home and run the household (“oikos”). However, some exceptional women, like Hypatia of Alexandria (mid-4th century-415 AD), managed to access education and make significant contributions to philosophy, astronomy, and mathematics.

There were also significant differentiations based on social class. Broadly speaking, education was the exclusive preserve of free-born male citizens, but not all citizens were created equal. Slaves, who constituted a massive portion of the population (around 40% in Athens; as high as 90% in Sparta), were denied access to formal education. But even among citizens, there were further distinctions based on socioeconomic status. The elites in Athens (the “Hippeis” or “Cavalry/Knights” class, for example) had greater resources to provide private tutors and a more comprehensive education for their sons. In contrast, the sons of less wealthy citizens might have received only basic literacy and numeracy skills, with limited exposure to philosophical or higher-level intellectual training.

It’s important to note that while these distinctions were pervasive, there were occasional exceptions and variations in different city-states and time periods. Freeborn Spartan women, for example, like their male counterparts (see below), received a state-sponsored education until the age of 18, which revolved around physical training – the idea being that they would be the future mothers of “Spartiates,” men who would take their place in the army.

Spartan women, who received a formal education until the age of 18, helped to enforce the state ideology of militarism and bravery.

© Public domain

Ancient Greek education was divided into several key components, each contributing to the comprehensive development of young individuals.

Physical fitness was highly prized in ancient Greece. The gymnasium, from which the term “gymnastics” is derived, played a central role in the education system. Here, boys engaged in activities like wrestling, running, and the pankration (a form of combat sport), which not only promoted physical health but also instilled discipline and camaraderie.

Education in music and the arts was also considered essential. This encompassed the study of poetry, music theory, and musical performance, typically involving the lyre – a stringed instrument similar to a lute. Music was believed to have a harmonizing effect on the soul, fostering emotional and intellectual development. The study of drama, including the works of 5th century BC playwrights like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, also held a prominent place in Greek education.

The ability to persuade and speak eloquently was highly valued in Greek society, especially in Athens. Rhetoric, the art of persuasive speaking, was taught extensively, and students studied the works of famous orators like Isocrates (436-338 BC) and Demosthenes (384-322 BC), honing their ability to present convincing arguments and influence public opinion.

Philosophy also played a crucial role, with prominent philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle influencing pedagogical approaches; Plato famously opened his own school for higher education, the Academy, in Athens, sometime around 387 BC. Philosophical discussions, debates, and the pursuit of wisdom were integral to intellectual growth and character development. It also encouraged critical thinking, questioning, and the exploration of moral and ethical concepts, shaping students into thoughtful and introspective individuals.

Mathematics, including geometry, was another integral part of the education system, so too literature and poetry. The study of epic poems such as the Iliad and the Odyssey exposed students to moral and ethical dilemmas, heroic ideals, and the complexities of human nature. Mastery of the language, including accurate verbal reasoning (dialectic), was also fundamental.

A 19th century artistic representation of Spartan boys exercising while young girls taunt them.

© Public domain

Established sometime in the 7th or 6th century BC, the Agoge, from the verb “to lead,” was the rigorous and highly distinctive educational system in Sparta, designed to mold young Spartan boys into formidable warriors and dutiful citizens.

Boys entered the Agoge at the age of seven and remained until they reached 18. Its primary focus was on physical conditioning, military training, and instilling unwavering loyalty to Sparta and its laws; an extreme form a military boot camp.

Boys were organized into age-based groups called “agelai” (“packs”), each overseen by an older boy, and they lived in communal barracks. Discipline, austerity, and toughness were integral aspects of the Agoge, and fighting within the packs was actively encouraged. Physical training included activities like wrestling, boxing, running, and, as they got older, combat skills and mock battles, with an emphasis on endurance and pain tolerance. The aim was to produce soldiers who were physically superior, mentally resilient, and fiercely dedicated to the Spartan way of life. They were taught to endure hardship, obey orders without question, and prioritize the collective good over individual desires.

The Agoge played a crucial role in Sparta’s military dominance, but it also contributed to the distinct and austere Spartan culture, emphasizing discipline, austerity, and a unique sense of duty to the state above all else.

The School of Athens by Raphael (1509–1510), fresco at the Apostolic Palace, Vatican City.

© Public domain

Ancient Athens was a thriving hub of intellectual activity during the 5th and 4th centuries BC and beyond, giving rise to various philosophical schools that profoundly influenced Western thought. These schools were diverse in their approaches to understanding the world, ethics, and the nature of reality. Three of the most prominent philosophical schools in ancient Athens were Plato’s Academy (387 BC), Aristotle’s Lyceum (335 BC), and the Stoa, founded by Zeno of Kition around 300 BC.

Members of the philosophical schools were young, intellectual elites; almost exclusively upper-class men, who had completed their primary and secondary education, and possessed the necessary resources to be free of financial concerns.

Plato’s program of higher education at his Academy, as described in his famous dialogue, “The Republic,” was devoted to the study of dialectics and mathematical reasoning. Students would have explored themes like justice, the nature of the soul, and the ideal state. Plato’s most famous student, Aristotle, also spent considerable time at the Academy before establishing his own school, the Lyceum.

Aristotle, whose works were more empirical and focused on the natural world, including the “Nicomachean Ethics” and “Metaphysics,” introduced a program that explored concepts like virtue, causality, and the nature of reality. Prior to founding the Lyceum in Athens, Aristotle had been the personal tutor of the future Alexander the Great.

"Alcibiades Being Taught by Socrates," by François-André Vincent (1776)

© Public domain

The pedagogical methods employed in ancient Greek education were often tailored to the individual needs of the students. In Athens, key elements of these methods included mentorship, dialogues and debates, and the so-called “Socratic Method.”

The relationship between teacher (“pedagogue”) and student was highly personalized. A pedagogue was not just an instructor but also a mentor who guided the moral and intellectual development of the student. This mentorship extended beyond the classroom and often involved discussions and philosophical dialogues, challenging the student’s ideas and developing their capacity for argumentation and persuasion.

Socrates, one of the most renowned educators in ancient Greece, employed a form of inquiry-based learning – the “Socratic Method.” He asked probing questions to encourage critical thinking and self-reflection, emphasizing the importance of self-discovery in the pursuit of knowledge.

Rote memorization also played a significant role, as students were expected to memorize and recite passages from literature and poetry, aiding in language acquisition and cultural immersion.

Aristotle (384–322 BC) founded the Lyceum in Athens in 335 BC.

© Public domain

"Aristotle Tutoring Alexander," by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1895)

© Public domain

The education system in ancient Greece left behind a profound legacy that continues to influence modern education systems in many parts of the world. The emphasis on holistic development, critical thinking, and the pursuit of knowledge remains central to contemporary education, and key elements of Greek pedagogy, such as mentorship and the Socratic method, have also found a place in modern teaching practices.

Moreover, the Greek educational system played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural and intellectual landscape of the Western world. By nurturing the minds and characters of young individuals, it produced some of the most influential thinkers, philosophers, and scientists in history, whose ideas continue to shape our understanding of ethics, politics, science, and the human condition.

A monument of memory and music,...

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...

From a mysterious Minoan structure to...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...