Agapi from Poland Finds Expression in the Art...

A Polish-born artist who lives on...

A young shepherd on the Lasithi mountains. The katsouna, a heavy walking stick made from the hard wood of the endemic Cretan zelcova tree, has always been an indispensable companion for the island’s cattlemen and often doubled as a weapon.

© Nikos Psilakis

Shortly before midnight at the Venetian fountain, in the heart of the city, four young men are walking arm in arm, singing. They’re wearing jeans and button-down shirts; two are wearing black shirts, the color of mourning. They’re obviously villagers visiting the city. A few surprised tourists point the lenses of their cell phone cameras at them; others pass by, indifferent. For the locals, it’s a recognizable sight, if not entirely common. A bit further down, on the road that leads to the port, one finds street musicians with drums and guitars, and crowded bars blaring out the international language of music.

The city is humming with life. It’s called Irakleio. But it might also be called Hania, Rethymno, Aghios Nikolaos. What changes? Only the name – not the soul. There are differences, of course, but wherever you go, you’re certain to be surprised. Whether it’s by big things or by details, it doesn’t matter – either way, you’ll encounter the excess called Crete.

The young men head off, singing, and disappear down the narrow side streets. The echo of their song still reaches our ears. But it seems to echo across time as much as space. It speaks of love, of forbidden love – and of unbearable separation:

How am I to part from you and leave?

How am I to live without you

when we part?

It’s strange, but these same verses have been heard on this island for over three centuries. It’s the favorite song here, a sort of peculiar local anthem. It comes from a much longer work, written shortly after 1600 in the dialect of the island (which largely survives to this day) by Vitsentzos Kornaros, a man of Venetian ancestry who was raised in the traditions of Crete. My grandfather, though illiterate, knew the whole epic by heart. All he could write was his signature, which he learned while in prison shortly after the last uprising of the 19th century – and when he held a pen, it seemed to me that he was holding a rifle; perhaps that’s how it seemed to him, too. But whenever he put his beloved on a horse and they rode from a village down in the plains up to his hideouts in the mountains, six hours away, he sang that epic to her on the journey. Always the same song, no matter how often they traced that same path, he sang it coming and going. The horse was always decorated in ceremonial style, with a woven blanket on the saddle – that’s how people traveled on feast days and holidays back then; it was a mark of nobility. The hours passed, but the song kept going. After all, with 10,000 rhyming iambic lines, how would you ever reach the end?

The song is called the Erotokritos. A chivalric romance in verse, thick with dialogue, it’s one of the great epic poems of the European literary tradition. Unfortunately, it is little-known outside of Greece because its linguistic particularities, a language full of charm, make it exceedingly difficult to translate.

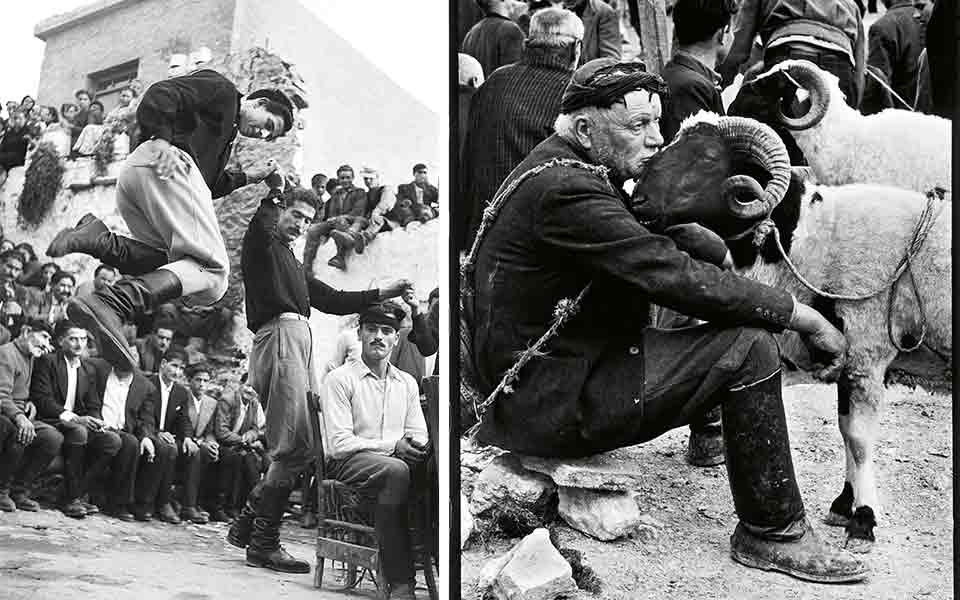

Going home from the fields. Kritsa, Crete, 1964. From the award-winning “Greek Portfolio” by the renowned Greek-American photographer Constantine Manos.

© Constantine Manos/Magnum Photos

I wonder what those young men were doing, wandering through the streets at night singing that song. Perhaps they were doing whatever my grandfather, a lifelong revolutionary, was doing when he sang that song astride his horse. An entire century separates those two eras – and a song unites them. There may be not a single Cretan alive today who doesn’t know at least a handful of its lines, who hasn’t sung them at some point. It’s sung in the company of friends, it’s available on CD and on the internet and it’s nearly always heard at festivals and celebrations, accompanied by the lyra, the local string instrument, even if it doesn’t really have a tune one can dance to.

Why the Erotokritos? The answer is provided by the lines themselves, which are full of love and war, of discord and serenity, of serenades outside windows, and of the clanging of swords. There’s combat and deadly jousting, but there are tender words, too. It’s a true hymn to beauty, to passion, to love – a hymn, that is, to life itself, sprinkled with distillations of folk wisdom.

It’s possible that this song is an image of Crete itself.

A few years ago, I found myself at a village festival in the foothills of western Rethymno region. It was April 23, the feast day of St George, patron saint of mountain dwellers. Cheeses were piled up outside the church – shepherds’ offerings, which the priest would divide up and offer to the crowd. Shortly before, village youngsters on horseback had paraded an icon of the saint through the streets. They were all in local costume, the sort of clothes very few still wear these days, and only then to promote their local identity. They went down all the streets of the village. A human stream followed this Byzantine icon that depicted the saint as a young man: strong, handsome and armed, grasping his bloody lance.

When the procession was over, the young men gathered again beside the church, 15 or 20 people, and began to sing. Here they didn’t sing the Erotokritos; they sang rizitika, ancient songs, the authentic voices of mountain-dwelling Cretans, those who lived brief lives in the badlands of history. They’re plain, austere, robust – a kind of echo of Byzantium that insists on crying out the fact that it exists. The songs speak of freedom and love and pain – perhaps the best picture of the enduring mentality of Cretans, who shape their identities with the mosaic tiles of their long history.

Men from the village of Kritsa in Lasithi dressed in traditional costumes, with beautifully embroidered petsetes (towels) on their shoulders, attend a Cretan wedding. The local cultural association helps sustain age-old customs.

© Nikos Psilakis

Today, in the first decades of the 21st century, many groups of young people in western Crete gather two or three times a week to sing rizitika, and to learn those songs they don’t yet know.

So, again, I wonder: how does all of this survive through time? And I answer myself: it is precisely this that is Crete.

I said I would write about Cretans, and I began with song. I don’t know if song calms the souls of these island inhabitants, or if it stirs them. From end to end, the island is an odd twinning of opposites: high, craggy mountains and cosmopolitan beaches. It is the great journey of history, it is coexistence with the other, it is friendship and conflict, conflict that led to great uprisings. The creator of the cosmos placed this island between three continents, close to other peoples. Africa and Asia are just a short sea journey away. But Crete remains an island, sealed in a world of its own.

Whenever I talk about Crete I always think of its landscape; peaceful and calm, yet wild. And I think of a dearly departed friend, the archaeologist Yannis Sakellarakis, who used to tell the story of how he once managed to condense all four seasons into a single day. He arrived on the island by ferry with a group of young archaeology students one morning. They took a walk, ate bougatsas (custard pies) in the square, and boarded the bus for Mt Ida. Their destination was the mythic cave where Zeus, the king of the gods, was said to have been raised.

It was April; snow covered the entrance to the cave, and the cold was biting. It was still winter up on the mountain slopes – there are years when the snow lasts into August. It’s strange for a Mediterranean landscape, bathed in sun, but Crete has three mountains whose peaks are almost 2,500 meters high. On the way back down into the plains, the bus was stopped by two shepherds who had just milked their sheep and were getting ready to make cheese. They asked everyone to get off the bus, and the students watched the milk being boiled in big cauldrons, just the way it must have been done a few thousand years ago on the very same mountain. In the end, the students were all offered fresh steaming myzithra, a whey cheese. Hospitality, treating strangers to what you have, is law in these parts.

But the journey wasn’t over yet. Shortly afterwards, they found themselves in a meadow. Countless narcissus plants – called manousakia on Crete – were in bloom, peeking out between the shrubs; white blossoms, like the snow they’d held in their hands just a little while earlier.

© Left: Dimitris Charissiadis/Benaki Museum photographic Archives, Right: Constantine Manos/Magnum Photos

It was afternoon when they reached the Messara Plain. Here, they found an entirely different landscape: an endless field of strawberries, bright red and fragrant. Another opportunity for hospitality: a treat of these berries was accompanied by raki, Crete’s local spirit and best-known drink. Their last stop that day was Matala, a small harbor to the south, once a poor fishing village, then a paradise for hippies, and today simply a tourist destination full of shops selling souvenirs. The sea was crystal clear, not a wave in sight. It stretched out beneath open ancient tombs and the caves where the hippies once lived. Who could resist taking a dip in the warm Libyan Sea?

One of the students looked at his watch. “Two-and-a-half hours ago I was shivering with cold in the snow!”

Four seasons in a single day.

And many more eras, I’d say.

I had to talk about the landscape because I believe it, too, has helped shape the Cretan soul. The land on Crete is at once rough and serene. This is a place where tradition becomes law, and then the law is broken. My fellow Cretans are honest, upstanding and unruly: with their local dances still popular today, with their songs, with the guns they shoot in the air to express joy, and with their famous Cretan knives, a symbol of the island, decorated with intricate patterns and love songs. Even today, the manufacture of these knives is one of the most important expressions of local folk art.

But folk art also seems to me to reflect contemporary Crete. Years ago, the katsouna, a local shepherd’s crook with a curved handle of hard, gnarled wood and an aesthetic that wavers between postmodern and grotesque, was a symbol of an agrarian and pastoral past, and young people rarely carried them. From time immemorial, this walking stick has been the necessary companion of farmers and shepherds, who used it for support on long journeys by foot, and, in periods of conflict, as a weapon. In recent years, it has become something of a symbol of local identity, an expression of Cretan masculinity. You see katsounas everywhere; in shops selling local wares and folk art, at roadside stands where they can be bought from those who make them, at farmers’ markets, and even at grocery stores. You see them at protests, too, and on the front pages of newspapers. Young farmers are proud to pose with their katsounas.

The foundation of the local economy remains agricultural. The gray-green olive tree is everywhere. Crete is perhaps the most densely planted olive grove in the world. But there are also vineyards, gardens, greenhouses and small orchards. Cretans are proud of their products, including olive oil, honey, cheese, wine, and rusks, and of the diet that incorporates such items.

Last year I found myself at a farmer’s house, where I was offered some of their homemade wine. I accepted the first glass. They offered a second. When they saw me hesitating, they said, “But it’s holy water.” Which is to say, the best in the world. There are, indeed, amazing wines being produced on Crete today. Of course, their own unrefined wine wasn’t one of these, and they knew it. I knew it, too. But I liked the pride they took in it.

And so, again, I wonder: what would this place be without excess, hyperbole? What would these people be? Haven’t all the great moments in their history been moments of excess? From isolated revolutionaries fighting against regular army forces to the men and women of 1941 who picked up their katsounas and pickaxes to fight the German paratroopers, who faced airplanes and machine guns with nothing but walking sticks. But those sticks weren’t only an extension of their hands – they were an extension of their souls. At that moment, the weight of tradition counted for more than the laws of cold logic. Centuries and centuries of Cretan defiance had taught them this.

© Efi Psilaki

Since the beginning of the 20th century, when the excavations of Minos Kalokairinos and Arthur Evans brought the history of the Minoan civilization to light, names from the world of myth irrevocably entered the life of the island. Minos, Ariadne, Knossos, Phaistos, Kydonia, Europa and Gortyna are now the names of ships, restaurants, tavernas and businesses, small and large. They are, in a sense, also aggressive designations. The word “Minoan” is often tacked on to goods and services of all sorts. A few decades ago, some learned folk thought of reviving Minoan architecture. They never managed to pull it off. But today, in many hotels, we find “Minoan” columns in that striking terracotta color. Houses in villages and cities on the island mimic the architectural forms that Evans discovered and recreated at Knossos.

Today, Crete is a major tourist destination. The alterations it has undergone are so great as to have changed the landscape itself. A Cretan from 1940 or 1950 wouldn’t even recognize the beaches on the northern shore of the island. Back then, they were deserted; now, they’re packed with more tourists than you might think possible. At the same time, our hypothetical time traveler would feel right at home at a local festival or a social event, such as a wedding. In these realms, changes happen more slowly. The entertainment spots may have changed, but the way people celebrate has stayed the same. Once, all celebrations, even wedding parties, took place in village squares. Today, they’re held in enormous halls that accommodate hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of guests. But they still involve the Cretan lyra, local dances and songs.

Whoever wishes to discover the soul of Crete today should know that they won’t find it on those crowded beaches. They’ll find it in the mountains, in the villages, in the wine, in the honey, in the oil and, of course, in the people.

I, too, wonder what Crete is. Most likely, it has something to do with what an old monk told me years ago. A shepherd came to his monastery one evening before dark. The monk didn’t recognize him, but he saw the man put a sizeable bill in the collection box and pray before each and every icon, from the smallest to the largest. A few days later, he saw the man’s photograph in the newspaper. He had been caught red-handed trying to steal another shepherd’s animals, a crime that has plagued Crete for eons. At the monastery, he had been seeking the saints’ help in order to commit an unlawful act.

There’s an idiomatic word that is still used today, kouzoulada, which I suspect that anyone who didn’t grow up on Crete would have difficulty understanding. Some people translate it as craziness, insanity, but that’s not really right. I prefer to call it passion, excess. Excess in love and in war, in serenity and in storm, in pride and in rage, in joy and in song.

What would Crete be without its people? It would certainly be a beautiful place, but there would be no celebrations, no voices raised in song, no dances, no Erotokritos, no guns fired in the air, no katsounas, no knives. There would be, I suppose, no kouzoulada.

A Polish-born artist who lives on...

From Santorini sunsets to ancient ruins,...

Where tropical fruit trees thrive beside...

What to do and where to...