What drives a collector’s passion? Is it the emotional connection sparked by holding a newly discovered piece? The aesthetic pleasure it provides? Or is it perhaps the potential for its value to grow with time? For Yannis Megas, a Thessaloniki native and civil engineer, the answer is a deep, personal connection to the history of his hometown. Over the years, he has amassed a remarkable collection, which he recently donated to the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, forever enriching the city’s cultural heritage.

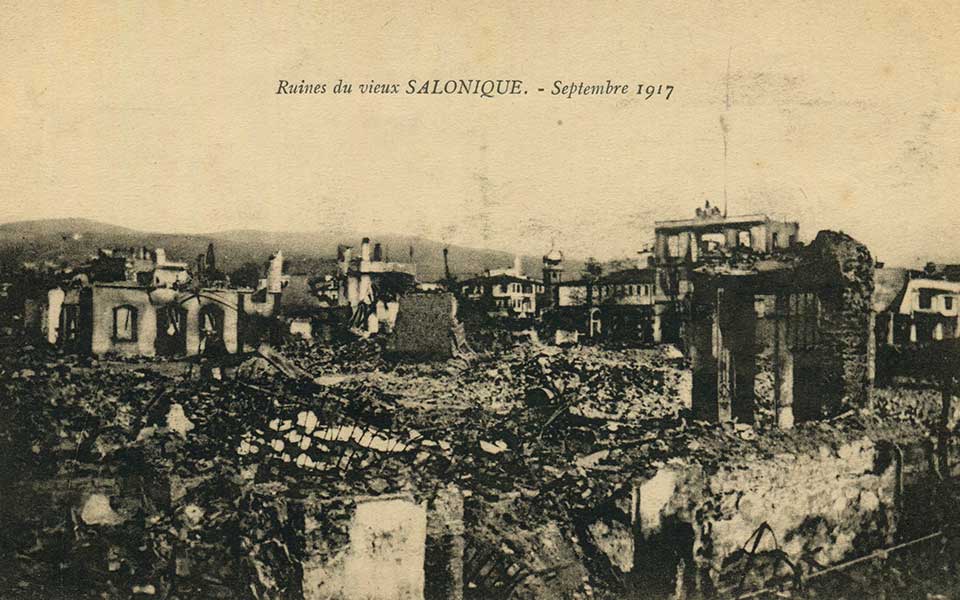

Born and raised in Thessaloniki with Jewish roots on his mother’s side, Megas left his hometown in the early 1970s to pursue postgraduate studies in transportation and traffic engineering in London. It was there, while building a life with his British wife, that his unique Thessaloniki collection began, and it started in the most unexpected way. One Saturday morning at Camden Market, Megas’ gaze landed on a stall brimming with postcards. Amidst the colorful assortment, one particular card stood out to him – a haunting image of Thessaloniki in the aftermath of the great fire of 1917, a tragedy that consumed nearly 9,500 homes and reshaped the city’s landscape.

© IOANNIS MEGAS ARCHIVE

© IOANNIS MEGAS ARCHIVE

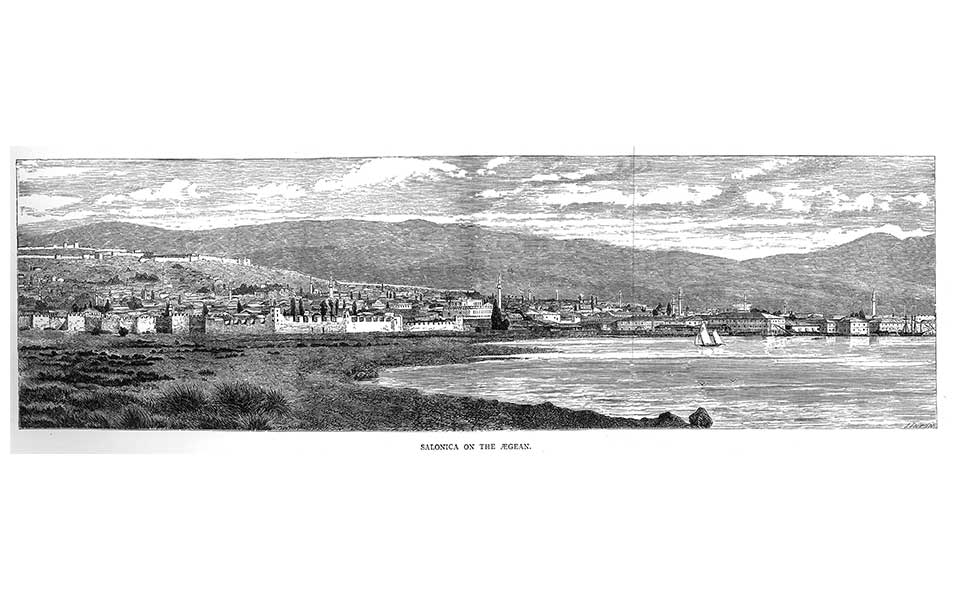

“Until that moment, I hadn’t realized the extent of the destruction – almost the entire city center had been leveled. That sparked my interest, and I bought three postcards depicting the aftermath of this catastrophe,” he tells me one October morning when we meet at his favorite café near the White Tower. Three cards from Thessaloniki quickly became ten, then twenty, and eventually an astounding 15,000. Many of these dated from WWI, when thousands of soldiers – British and French among them – passed through Thessaloniki. “Postcards were their only means of communication,” the collector explains.“I remember finding a French soldier’s entire correspondence, with postcards sent to his wife every day for 32 days. The postcards were numbered, each one describing his daily activities – never a word about the war itself. Through these cards, I was able to glimpse at the lives of so many people.” Wherever he traveled, Megas always searched for things connected to Thessaloniki. What began with postcards soon led to photographs, then to engravings – some dating back to the mid 1800s. Soon, he was scouring magazines from England, France, Germany and Russia, and eventually rare books, too. His remarkable collection spans a century, from 1850 to 1950, with a particular emphasis on the Ottoman era and the city’s history up to 1912, although it also includes items from as late as the 1980s.

“I was only interested in Thessaloniki – nothing beyond it. Not even its surrounding areas,” he says. Collecting thousands of artifacts tied to the city’s history – from every corner of the globe, including Europe, New Zealand and Africa – became, in a way, his way of reconnecting with the city where he was born. Through his collection, he rediscovered his hometown, even while far away from it. What began as nostalgia soon turned into intellectual curiosity. The more he learned, the more he felt compelled to delve deeper into Thessaloniki’s identity. He meticulously cataloged each item in his collection, creating a digital archive that documented the type, date and theme of every artifact. For Megas, the process of collecting became a form of exploration, a way to piece together the fragmented history of his city; a passion that he pursues to this day.

“As an engineer, I had little connection to the literary world. There were so many things I didn’t know about Thessaloniki’s history. Collecting taught me so much – so much, in fact, that it eventually led me to writing. These postcards weren’t just pictures of the White Tower or the seafront. They were historical snapshots, capturing real events. They told stories,” he explains.

© IOANNIS MEGAS ARCHIVE

Rescuing history

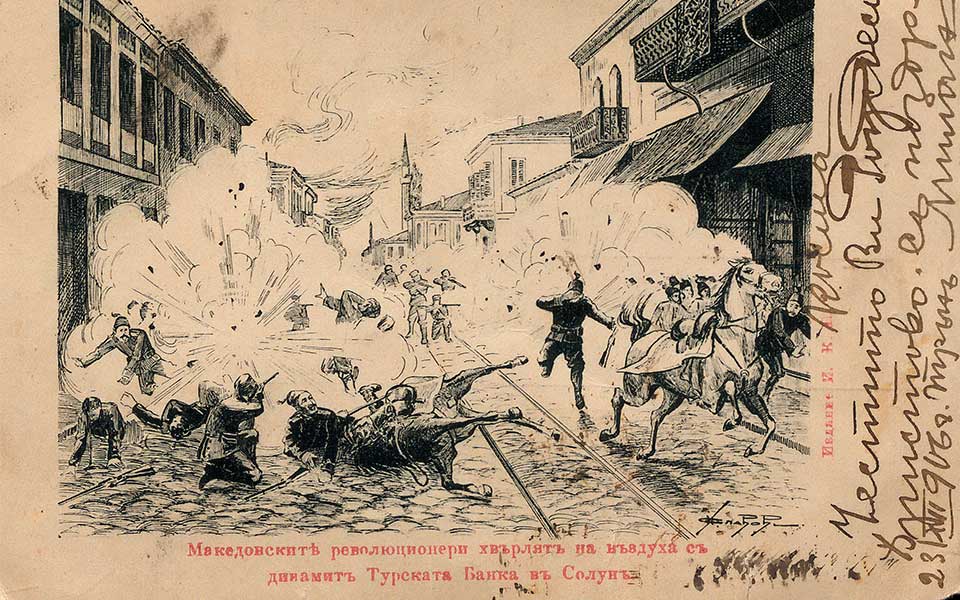

One such story became quite important to Megas. “In 1903, Bulgarian anarchists launched a series of terrorist attacks in Thessaloniki. They blew up a ship in the harbor, planted explosives in the Ottoman Bank, and caused widespread destruction. I came across a series of 25 postcards documenting these events. A professor friend of mine tried to discourage me from delving deeper into the subject. Undeterred, I went to the National Library of Sofia, where I uncovered a wealth of material about what had happened. Here in Greece, that story had been largely forgotten, likely overshadowed by the broader Ottoman narrative. That research eventually led me to publish the book ‘The Boatmen of Thessaloniki,’ named after the group.”

To date, he has written thirteen non-fiction books, which include “Kidnappings and Murders in Thessaloniki 1852–1913,” “The Downing of the Zeppelin (May 1916),” “The Allied Troops: The Babel of Nations,” and several others. For Megas, the period leading up to the city’s liberation in 1912 is crucial to understanding Thessaloniki’s evolution. Thessaloniki had been the cultural and economic center of the Balkans, but after it became part of Greece, it was suddenly a second-tier city just thirty kilometers from the border, losing much of its prominence.

© IOANNIS MEGAS ARCHIVE

Equally vital, he highlights, is the role of the city’s Jewish community. “My first book is called ‘Souvenir: Images of the Jewish Community, Salonika 1897-1917.’ It’s a bilingual book exploring the everyday life of Thessaloniki’s Jewish population. It covers everything from the trades people practiced and the homes they lived in to the religious events and the role of rabbis in the community, all brought to life with postcards from the era.”

Every postcard, engraving, photograph, or book in his collection was a gateway to a new historical discovery for him. “During a trip to Vienna, I visited an antique shop and came across a postcard written in code” Megas says. “Years later, I discovered a society in Germany dedicated to decoding encrypted messages. I sent them the postcard, and they translated it for me. The message itself was trivial, but that wasn’t the point – it was the journey of discovery that mattered.”

Megas’ latest book, soon to be published, concerns the diplomatic role that the city played from 1684 to 1912. “I was amazed to learn that the city had 25 consulates over that period,” he says. “I reached out to the foreign ministries and archives of all those countries. Almost all of them responded, sending material about the consuls, their biographies, and other details, so I began documenting their stories.”

© IOANNIS MEGAS ARCHIVE

Open source

A particularly treasured part of his collection is the photographic archive of Giorgos Lykidis, a Thessaloniki-based photographer who passed away in 1967, which he acquired from Lykidis’ heir. Lykidis captured iconic moments in Greek history, such as the battleship Averof and the Greek fleet entering Constantinople’s port in 1922. He also photographed Thessaloniki’s most renowned landmarks, its main streets and the frescoes adorning the interiors of its churches. Following the devastating earthquake of 1978, Megas donated some of Lykidis’ photos of frescoes to the Department of Modern Monuments. These became crucial reference material for restoration work in sites ranging from the Rotunda to the Church of the Aghioi Apostoli, helping preserve the city’s religious heritage for future generations.

For Megas, his work as a collector has always been deeply personal and has given his life a distinctive sense of purpose. “Documenting everything takes time. Especially after retirement, I realized how important this collection has been in giving me purpose. I’ve never spent my days idling in coffeehouses. If I didn’t have this passion project, I don’t know what I would have done,” he says.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Megas’ collection transformed him into a writer and provided him full access to the city, both past and present. “In recent years, anyone writing about Thessaloniki reaches out to me for material, and I really enjoy that. My collection has always been open to everyone. There are collectors who keep their collections hidden – no one sees them, no one knows about them. Mine, on the other hand, has always been accessible.”

But does a collection ever truly reach completion? “I stopped acquiring new items after I donated the collection to the University. It was given to the Central Library, where there was adequate space for storage and enough staff to care for it. At first, I had my doubts about handing it over to

Aristotle University. I didn’t want it to be broken apart – I wanted it preserved as a whole. But going with the University turned out to be, by far, the best decision I could’ve made. Along with my collection, we also donated the collection of the poet Dinos Christianopoulos, who was a relative of mine. We made that decision together before Dinos passed away.”

Since its arrival at the University in 2017, Megas’ collection – packed in seventy large boxes – has been carefully cataloged, and is being digitized by the University staff. That process is painstakingly meticulous. Every item must be properly identified before being uploaded to the system, and that level of detail requires a significant investment of time and effort.

How does he feel now that the collection is no longer in his possession? “I’m very pleased because they’re doing an excellent job. I know that if I ever need anything, I’ll be able to find it immediately.” I press him further: “Don’t you miss having it at home?” “Not at all,” he replies firmly. “The collection was stored in a different apartment anyway. I sold that place when the collection went to the University.”