14 Stunning Rooftops in Athens for Food, Views...

From Michelin-starred tasting menus to sushi...

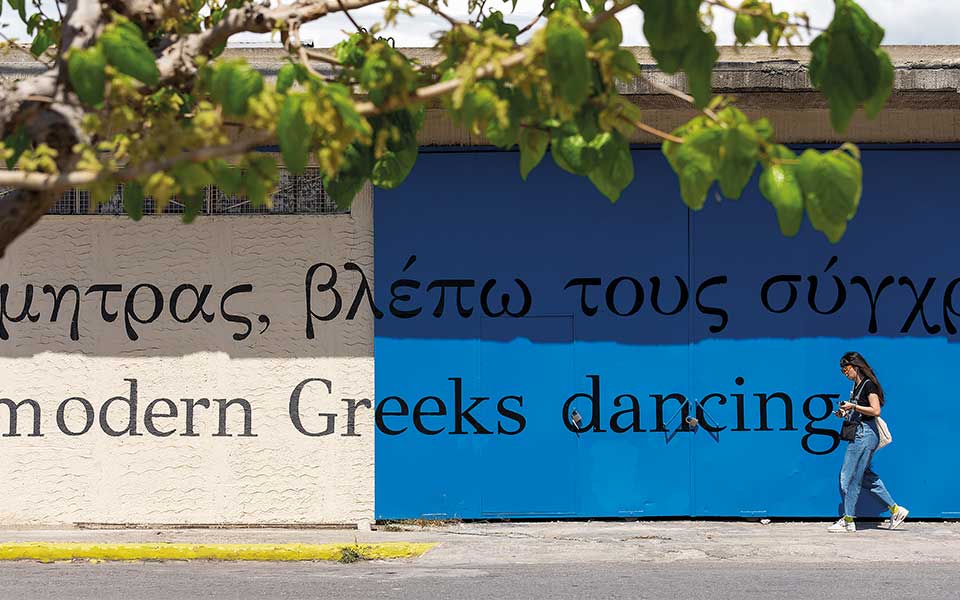

Lines from American poet Walt Whitman’s poem Proud Music of the Storm (“Again, in Eleusis, home of Demeter, I see the modern Greeks dancing...”) on a rural warehouse.

© Thalia Galanopoulou

If you tell an Athenian that you’re heading to Eleusis, they’ll likely respond with a mixture of surprise and confusion. “Eleusis? Why are you going there? How does one even get there?” Even though the city is just 21 kilometers from the center of Athens, Eleusis is not a place that many Athenians know well. Located on the far side of Mt Aigaleo, overlooking a beautiful bay, and accessible from the capital via Athinon Avenue, Eleusis is home to only 25,000 residents; it has nonetheless been designated as one of the European Capitals of Culture for 2023, sharing that honor with Veszprém in Hungary and Timisoara in Romania.

The news that Eleusis would play host to one of Europe’s most prestigious cultural institutions caught many by surprise. Among the Greek cities that had expressed interest in claiming the title were Kalamata, Rhodes Town, Corfu Town, Volos, and Ioannina – all with sizeable populations and rich artistic heritage. One might have thought that Eleusis, in comparison, had little chance. However, its unique blend of an enigmatic past linked to ancient rites and an industrial heritage made more visible by abandoned factories and smokestacks, played in its favor.

Finds from the archaeological site, with the facilities of the Old Olive Mill, which hosts artistic events for the European Capital of Culture and the local festival “Aeschylia,” in the background.

© Vangelis Zavos

The highest point in Eleusis is a hill on which you’ll find both the ancient Acropolis and the town’s Archaeological Museum. Established in 1899, this is one of the oldest museums in Greece; to reach it, one must traverse the archaeological site, home to the Sanctuary of Eleusis, one of antiquity’s most significant religious centers.

Located on the edge of the Thriasio Plain, which was once Attica’s largest granary, Eleusis was involved in livestock farming but relied primarily on agriculture. This explains its association with Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, and her daughter, Persephone. The myth of Persephone’s abduction by Pluto inspired the bards and playwrights of antiquity and formed the core of the Eleusinian Mysteries. These religious ceremonies, lasting nine days, began with a procession from the Acropolis along the Sacred Way to Eleusis. The Mysteries commemorated the desperate search of the goddess Demeter for her daughter, embodying a symbol of human reconciliation with death. Despite the secrecy surrounding the Mysteries, they are believed to have been centered in the three carved caves of Plutonium, the temple of the underworld God, where a small number of polytheists still honor the goddess Demeter by leaving fruits and vegetables. The recent renovation of the Archaeological Museum includes an exciting addition: a representation of the initiates’ entrance into the Telesterion, marked by the sound of flutes and a transition from darkness to a space flooded with light.

A panoramic view of Eleusis from the hilltop home of the archaeological museum. The Church of Aghios Georgios, patron saint of the city, and the port cranes, stand out.

© Thalia Galanopoulou

Seventy years ago, laundry left outside went stiff from the dust from cement factories. Today, those factories have closed.

© Thalia Galanopoulou

An oil tanker moored at the port of Eleusis.

© Thalia Galanopoulou

A bird’s eye view of Eleusis reveals concrete apartment buildings, towering factory chimneys, ship graveyards, and expansive grain warehouses. These elements of the city’s recent history are only part of the story; the long stretch of centuries predating industrialization have their own echoes. The Byzantines disrupted the legacy of the Telesterion, ushering in a new era of Christianity. The Franks and Venetians left their footprint through the towers they constructed, and their attempts to pilfer from the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore. British travelers endeavored to extract colossal statues from the Sanctuary, while Greek fighters camped in this vicinity, then inhabited predominantly by Arvanites, a bilingual population group of Albanian origin, during the 1821 Revolution.

In the early 1920s came the refugees. The fertile fields and vineyards gave way to housing for refugees from Asia Minor. Further dwellings were built for workers flocking from all over Greece to find employment in Eleusis’ new industries. Housed in one of Europe’s first industrial buildings made from reinforced concrete, the KRONOS company produced wine and spirits. VOTRYS catered to the demand for lighting alcohol; IRIS, with its prominent chimney, was a paint and varnish factory. TITAN’s cement served as the primary construction material for Athenian buildings.

The remnants of the ancient world gave way to a microcosm of modern Greece, complete with the scars of unregulated industrialization that marked the early to mid-20th century period. In the 1950s, the children of Eleusis were sweeping cement from the streets. If a housewife left laundry hanging out overnight, cement dust would harden the clothes by morning. Citizens born in the 1950s recall no sunny childhood days, just endless smog and grime. Although most factories closed or drastically reduced production in the 1980s, the area’s waters still remain unfit for swimming.

In a small harbor in town, local fishermen set up crates with the day’s catch.

© Thalia Galanopoulou

Cyclists stopping in front of the metal whale, part of the Opening Ceremony celebrating the city's designation as a European Capital of Culture.

© Thalia Galanopoulou

Time has changed much about Eleusis, but the stories of its inhabitants testify to a past that remains relevant. Philippos Koutsaftis’ documentary film Agelastos Petra (“The Mirthless Rock”) bears poignant testimony to this fact. Over twelve years, starting from 1988, the director meticulously documented how the city was being transformed by deindustrialization and the appropriation of archaeological sites for the purposes of residential construction. The film, featuring Panagiotis Farmakis, a native of Eleusis, premiered in 2001 and has since become a touchstone of Greek cinema; it provides an insightful introduction for those keen on solving the modern mystery of why Eleusis was designated a Cultural Capital.

Locals enjoying a musical event outside the Chapel of Aghios Nikolaos.

© John Stathis

The residents of Eleusis exhibit an undeniable warmth and openness, taking immense pride in their city. They journey to Athens only when necessary, enjoying their town’s relative tranquility. The city of Athens isn’t a prerequisite for their entertainment – they find contentment in their local hangouts. Gathering places include cafés such as Odemisio, formerly a ticket office and bus-stop offering basic café service that’s now a modern brunch hotspot in Upper Eleusis. Other popular locations include the Cyclops café opposite the archaeological site and the cyclist-oriented café, Be Bike. Locals procure their essential food items (and the local pasta known as “tzolia”) from Antoniou’s grocery store. Enjoyment comes from meals in the seafront fish taverns and relaxing evenings spent in the stylish coffee houses along pedestrianized Nikolaidou Street. From these vantage points, they admire views of the ancient ruins and the small Church of Panagia Mesospilitissa, a local incarnation of the Virgin Mary to whom Eleusinians offer baskets filled with grains and legumes.

Local residents have been enthusiastic participants in the Capital of Culture events hosted at the city’s various cultural spaces so far, turning up in numbers at venues such the Old Olive Mill and the former Iris factory. Driven by curiosity or genuine interest, they’re actively engaging in the city’s embrace of culture as a cornerstone of its new identity. At the ceremony kicking off Eleusis’ reign as European Capital of Culture, the city’s twelve civic associations, each representing members of a different ethnic background, comprised the event’s heart. Today, Eleusis is skillfully leveraging its ancient history and the rise and fall of its industrial legacy to lay a robust foundation for its future. The title of the European Capital of Culture does not promise a panacea for the city’s challenges. However, it serves as a beacon and an opportunity, ensuring that the city will continue to evolve and not stagnate. The people, the true lifeblood of the city, will chart their own path to the future. This journey may remain a mystery, just like the ancient Eleusinian mysteries, but it is one they are happy to embrace.

• Mystery 3 Elefsina Mon Amour: In Search of the Third Paradise (07.07–30.09). This international group exhibition, curated by Katerina Gregos – Artistic Director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens – features 16 artists from nine countries and posits a socio-political reading of Eleusis and the Thriasio plain. It constitutes both a study of and a testimony to modern Eleusis.

• Mystery 35 Αeschylus Project – The Eumenides (15-16.07, The Old Olive Mill) The trial that features in the play The Eumenides (The Furies) is one of the earliest accounts of a legal hearing in world literature. This court case examines questions of guilt and innocence as well as issues of judgment. Residents of Eleusis are invited to take an active role in the trial, playing a part in the proceedings.

• Mystery 35 Αeschylus Project – Iannis Xenakis: Oresteia (23.07, The Old Olive Mill) The Athens State Orchestra will perform a work considered one of the most important of the musical avant-garde of the 20th century, by the Greek musician, architect, mathematician, intellectual and philosopher Iannis Xenakis.

• Mystery 35 Αeschylus Project – The Persians _ a journey in the array of souls (29-30.7) This show, with performance elements directed by Nikita Milivojević, will start from the port of Perama Megaridos at sunset and take spectators by boat to the island of Salamina and, when night falls, to a deserted area of the island facing the stretch of sea where the 480 BC Battle of Salamis took place.

• Mystery 11 Ma (01-13.9, The Archaeological Site of Eleusis) This new creation by Romeo Castellucci is a walking experience/performance specially designed for Eleusis᾽ main archaeological site. The protagonist of Romeo Castellucci’s performance will be a matricide who is also non-Greek – that is, a foreigner. The dramatic action reactivates ancestral and contemporary tensions in relation to the earth, the same tensions that once gave form to the Mysteries

of Demeter.

• Mystery 14 Human Requiem in Eleusis (22.9-1.10, The Archaeological Site of Eleusis) The ancient Eleusinian Mysteries constitute the starting point of this site-specific re-creation of Human Requiem, a work based on Johannes Brahms’ Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem). Conceived & directed by Jochen Sandig, choreographed by Sasha Waltz, and with set design by Brad Hwang.

From Michelin-starred tasting menus to sushi...

From Santorini sunsets to ancient ruins,...

Recycling is an age-old tradition in...

On her first ever holiday alone,...