The ancient Greek poet Hesiod, in his didactic poem Works and Days written at the end of the 8th century BC, at some point advises his brother Perses how to prepare the grapes in order to make sweet wine: “When Orion and Sirius have come to the middle of the sky and the rosy-fingered Dawn can see Arcturus, then, Perses, cut and bring home all the grapes. Show them to the sun for ten days and ten nights and then in the shade for five and on the sixth day put into the jars the gifts of Dionysus, generous in joys.” This excerpt is the first from which we learn that in Greek antiquity sweet wines were produced from grapes that were laid out in the sun so that part of the water contained in the berries could evaporate and their juice would be concentrated. They were then crushed and the must was collected in jars and left to ferment. However, the must from grapes semi-dried in the sun was very thick because of its high sugar content, as we know today, which is why fermentation took several months and stopped when the cold winter weather set in, without all the sugar having fermented. So the wine remained sweet.

In fact, most of the famed wines of Greek antiquity were sweet. This technique has survived for centuries to the present day. The wines produced today in Greece from grapes semi-raisined in the sun are called liasta, the wines of the sun. They are of course made using modern technological methods. The production of another type of sweet wine, fortified wine, is based on the fact that the yeasts that turn the must into wine are living organisms with a lesser or greater tolerance to alcohol. Consequently, if during fermentation the winemaker adds enough alcohol, it will prevent the yeasts from multiplying and remaining active, resulting in a sweet wine that owes its sweet taste to those sugars in the must which did not ferment, and it will contain alcohol not only from the fermentation of the sugars but also from the aforesaid addition.

Naturally, sweet wines of this type could not be made in ancient and Byzantine times. They began to be produced in western Europe when the distillation of raw materials became widespread, particularly – at first – in monasteries where the various elixirs were made. In Greece today, both these methods are used to produce many splendid semi-sweet and sweet wines. I shall limit myself to a brief presentation of certain wines in the Protected Designation of Origin category.

“The “new” wines of Samos have all the aromatic richness of muscat grapes, while those which undergo long aging acquire the character of rancio wines.”

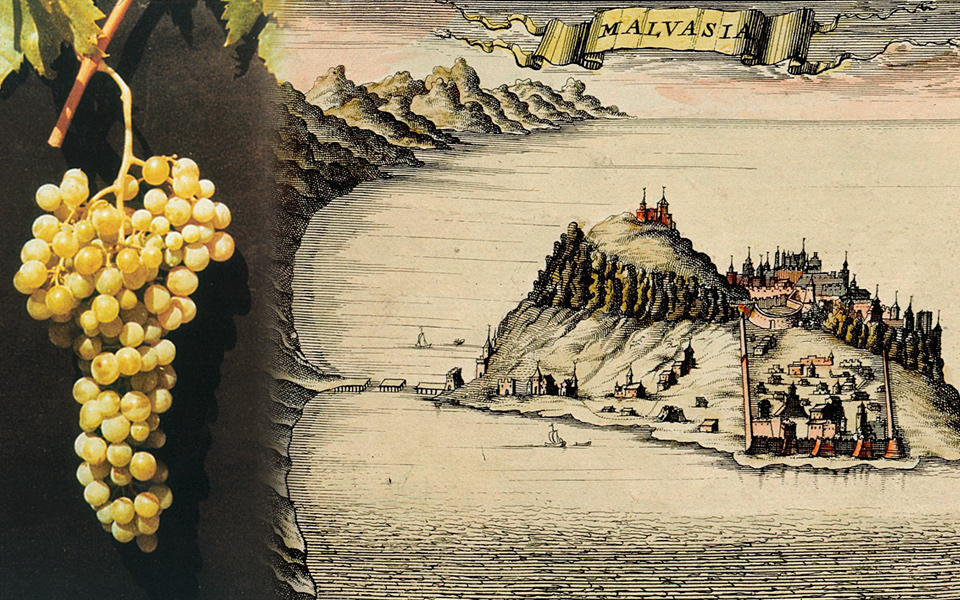

MALVASIA

In the Peloponnese, on the southeast shore of the Parnon mountain range, stands the Byzantine fortified town of Monemvasia, built in the 8th century on a towering rock separated from the mainland. According to written sources, the wine produced across the narrow stretch of water in the Laconian hinterland was exported for at least five centuries (11th-15th). Monemvasian, Venetian and Genoese ships loaded the wine in the harbor of Monemvasia, the fortress town at the foot of Malevos – as Parnon was known at the time – from which the Frankish name for the town, Mal(e)vasia, derived. And because in sea trade a commodity would often bear the name of the port in which it was loaded, the wine became known in foreign markets as Monemvasia or Malvasia, depending on the nationality of the traders.

This sweet wine was made from a number of grape varieties, including a predominant one whose name has been lost. However, when the Venetians took vine cuttings for their vineyards on Crete, which they had ruled since the 13th century, they naturally called it Malvasia, after the name of the port of shipment. In many travelers’ books, there are references to the cultivation of Malvasia also on the Cyclades islands, where it survives to this day with the Greek name Monemvasia.

In the town of Monemvasia, there was a community of Venetian merchants who sent sweet Malvasia to Venice via Crete. But after the Ottoman Turks occupied the Peloponnese, Malvasia was produced and exported only from Crete, thanks to the commercial activities of the Venetians.

However, the grapes of the Malvasia variety cultivated on Crete represented only a small percentage of the native varieties grown on the island, from which the sweet wines were made and for which Crete had been famous since ancient times. For this reason, during the centuries when the Venetian-Cretan wine trade was at its height, the Malvasia wine of Crete was a blend of several varieties. What is undisputed is that the celebrated Malvasia (Malmsey) wine was produced for eight centuries in the geographical triangle of Monemvasia – Crete – Cyclades. Which is why the wines of the sun produced today in these regions are the only Greek wines that are permitted to be traded under the name of Malvasia, accompanied by one of the four geographical names that have been given PDO status: Monemvasia, Candia, Sitia and Paros.

SAMOS

The island has been known since earliest times for its “Muscat with small berries,” which is the official name of the white cultivar from which the muscat wines of Samos are produced. Three different types of liqueur wines are produced (Vin doux, Grand Cru, Anthemis) along with one liastos, the Nectar. The “new” wines have all the aromatic richness of muscat grapes, while those which undergo long aging acquire the character of rancio wines.

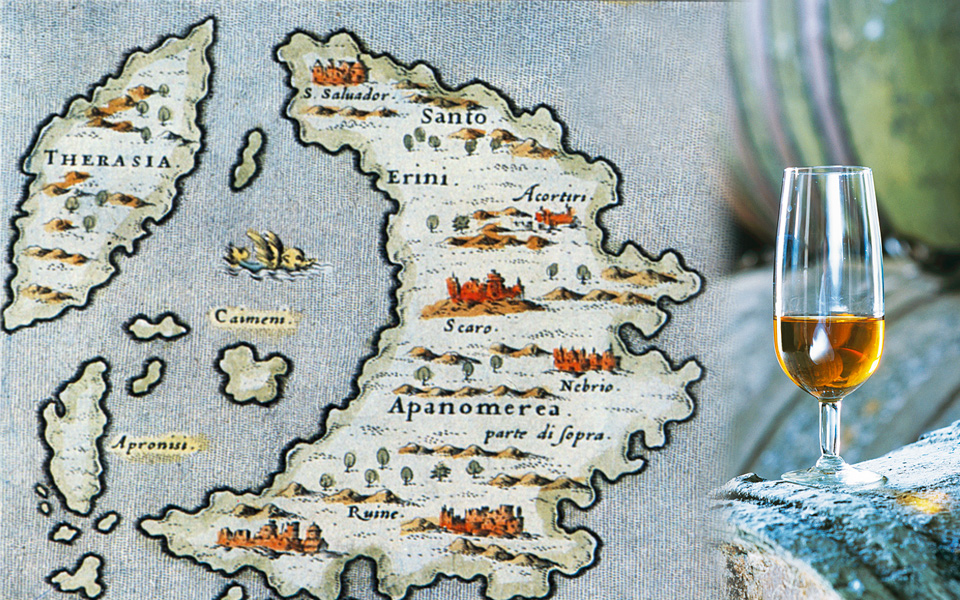

VINSANTO

On Santorini, there is a liastos wine that is made predominantly from the Assyrtiko variety, a notable multi-dynamic winegrape. According to maps and books by travelers, this type of wine was being produced on the island from as early as the 16th century and went by the name of Vin Santo. According to Abbe Pegues, prior of the Monastery of the Lazarists on Santorini (1824-1837): “The vin Santo is even better when it has aged. Then it is like a balsam which one feels in the mouth and the stomach. It can be served at the table of kings and given distinction in their toasts.”

This name, carried to this day by some dessert wines of northern Italy, is a vestige of Frankish rule on Santorini and the involvement of the Venetians and the French in the trade of the island’s wines. In the framework of EU legislation, this indication is permitted to be written on the labels of Italian wines accompanied obligatorily by a geographical name (e.g. vino santo di Gambellara). Thus, the indication Santo, from a geographical appellation, has degenerated into a generic designation of the type of wine, but the Greek Vinsanto is a PDO: Vin[de] Santo[rini]. This view was accepted after negotiations, ratified by the relevant EU regulations and reflected by the labels of the contemporary Santorinian Vinsanto.