The written entry in the works diary was brief but momentous, indicating the end of an era in Athens: “July 7, 1870 – Hut of the stylites on the columns of the Olympieion demolished. Cost of demolition 160 drachmas.” Thus wrote archaeologist Panagiotes Eustratiades, Greece’s general ephor of antiquities between 1854 and 1884.

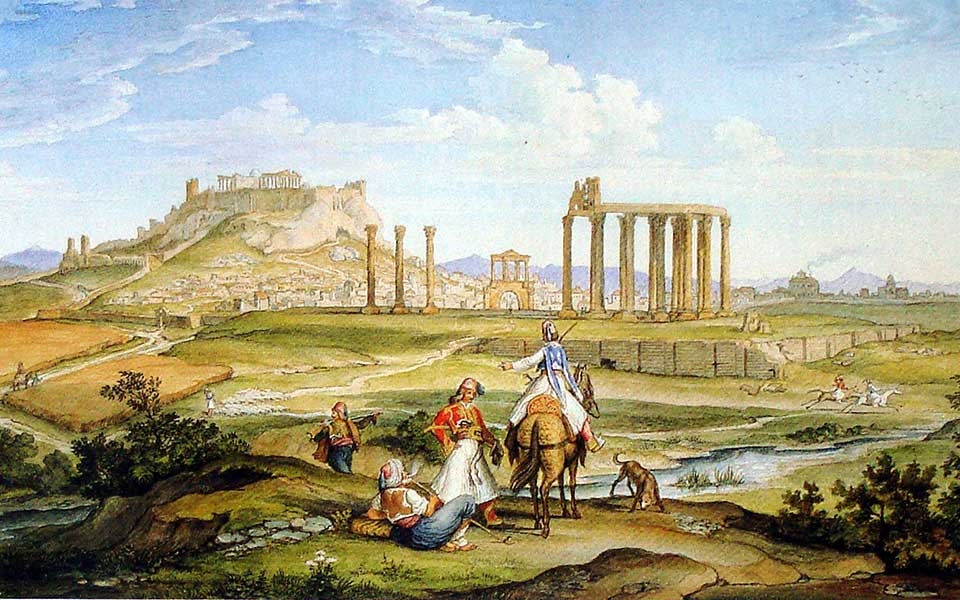

The “hut” (kaliva) referred to in Eustratiades’ diary was the dilapidated ruin of a possible Byzantine structure of brick and/or stone that had long appeared in numerous drawings, paintings and photographs by early modern artists and photographers in Athens.

For centuries, this distinctive but little-noted architectural feature had perched high up on the columns and horizontal architraves of the Greco-Roman Temple of Olympian Zeus (aka the Olympieion) – some 20m above the ground – like a lonely eagle’s aerie. Apparently it was inhabitable, as Athenians and foreign visitors at various times reported it was being used as a shelter by an ascetic, stylite monk seeking elevated, isolated solitude.

© The Museum of the City of Athens, Vouros-Eutaxias Foundation

Draconian Policy

During the 19th century, however, this humble but familiar detail of the Athenian landscape, like so many other Byzantine and medieval structures on the Acropolis and elsewhere, fell victim to a draconian archaeological policy, which called for the stripping away of unwanted architectural additions that had come to obscure Athens’ ancient, especially Classical remains.

The removal of these post-Golden Age accretions allowed the fledgling modern Greek state to present only select archaeological monuments as symbolic, less encumbered reminders of the past glories of ancient Greece. In 1870, therefore, the “hut of the stylites” was dismantled and disappeared forever, a little-remembered archival detail in Athens’ fascinating medieval and early modern history.

A Mysterious Ruin

Today, no trace of the stylites’ refuge is visible to Olympieion visitors. The masonry one can presently see on top of the temple’s lofty columns belongs to modern rubble caps that cover iron beams installed in 1892 by architect Ernst Ziller to reinforce the monument’s entablature. Nevertheless, questions have arisen concerning this incongruous, oddly situated structure that once stood atop the temple’s striking ruins.

Some observers have begun to doubt that stylite monks ever occupied the late construction, seemingly after a brief examination of the subject in 1996 by the late Charalambos Bouras, professor of ancient architecture at the National Technical University of Athens.

Yet despite Bouras’ assertions to the contrary, early 20th century testimony from a then-living informant suggests that as recently as the middle of the 19th century a stylite monk was indeed in residence on top of the Temple of Olympian Zeus – only a few years prior to its demolition.

Early Christian Asceticism

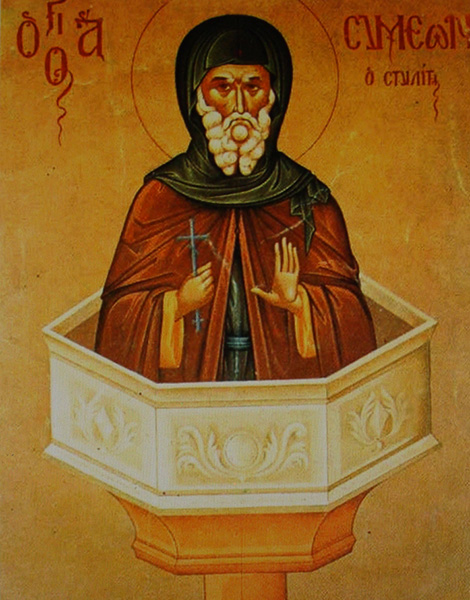

The practice of stylitism – living upon a column or pillar (stylos) – was an extreme form of asceticism in late antiquity, which may have originated in the early 5th c. AD and was known for many centuries thereafter.

Its apparent founder was the Syrian Symeon the Elder, a resident of Antioch, who first ascended a pillar in AD 412. Symeon and his like-minded followers sought out such isolated retreats in order to distance themselves from the concerns and sinfulness of an ordinary material existence.

Moreover, their elevated dwellings placed them symbolically closer to heaven and allowed them to be viewed by those below as leading an exemplary life more like that of angels than of humans.

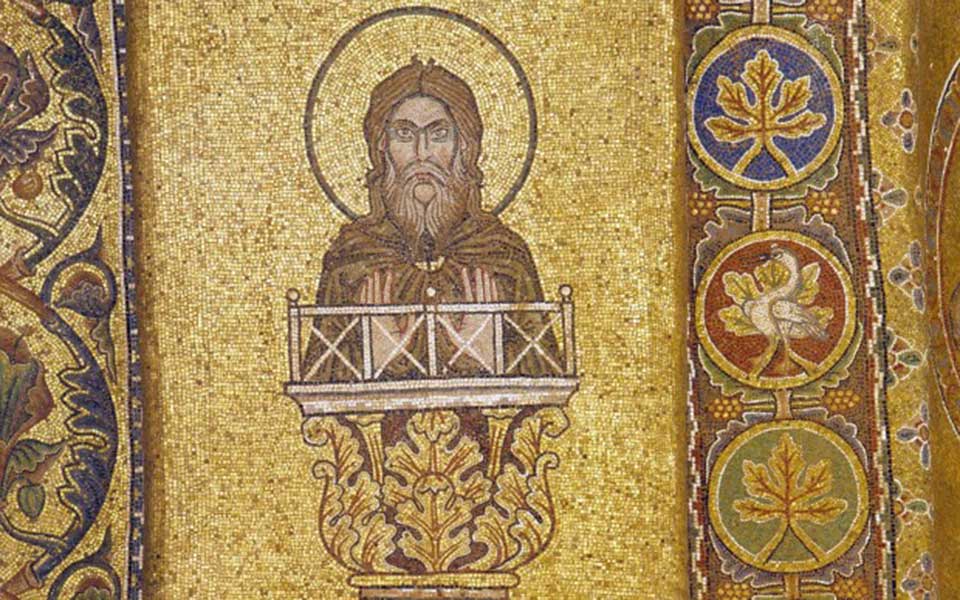

Byzantine icons and other pictorial or textual evidence reveals that stylites often built small platforms or boxes, usually of wood, which could be accessed when necessary by removable ladders. Temporary scaffolding was also sometimes erected beside a column or pillar at the end of a stylite’s life to remove his body.

In the case of the Olympieion in Athens, one has to wonder, given the temple’s gigantic size, how any stylite monk would have been able originally to reach his secluded aerie, and how, after death, his worldly remains would have been retrieved.

Near Eastern archaeologists have identified stylites’ columns through cuttings sometimes made in the stone to accommodate iron clamps or sleeves needed for reinforcing the monks’ improvised pedestals.

Larger niches carved in the columns held sacred objects, icons, or relics of the deceased stylite. Perhaps niches visible today in the Olympieion’s columns were late additions intended for a similar purpose.

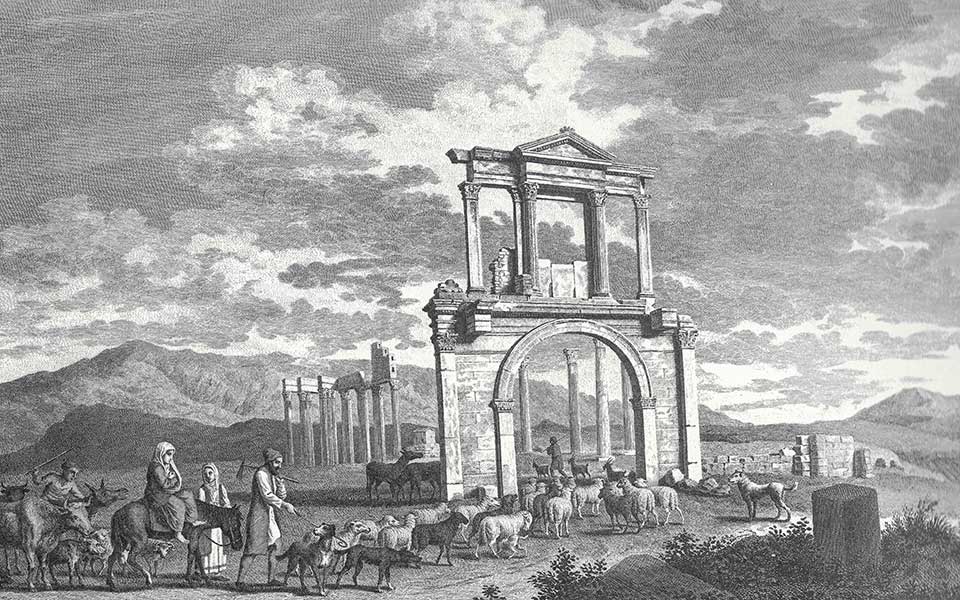

© Stuart & Revett, Antiquities of Athens III, Ch.3 Pl.1

Hadrian’s “Palace”

Although the enormous Temple of Olympian Zeus was founded in the late 6th century BC, it’s construction was soon abandoned, sporadically continued in Hellenistic and possibly early Roman times, then completed by the Hellenophile Emperor Hadrian in AD 132. Eventually succumbing to destructive invasions and natural calamities, its picturesque ruins became the stuff of medieval and later legend.

From at least the 17th century, the Olympieion was popularly claimed to be Hadrian’s palace, while the singular structure rising above the columns was sometimes said to be the remains of the palace’s main complex.

With the arrival in Athens of architects James Stuart and Nicholas Revett in 1751, the urban myths were finally dispelled by their proper identification of the “Temple of Zeus Olympius.” Nothing was said of the purpose or date of the masonry addition at the top of the temple, however, despite it being clearly discernable in two of the architects’ engraved illustrations.

A Fortified Tower?

Two centuries later, Bouras, in asserting that the “stylite’s hut” was too substantial and atypical to be a stylite dwelling, notes it “had three stories and in general resembled a tower.”

His study of 19th century photographs revealed the now-lost structure, founded above the Olympieion’s inner-peristyle columns at its southeast corner, was composed of ancient or Early Christian spolia (reused material), with several apparent repairs or renovations.

At least two windows opened on each side, while the interior floor-space would have amounted to an area about 1.35 m wide by 7 m long. Bouras suggests a construction date in the early or middle Byzantine era, prior to AD 1000.

Bouras also concluded, “there is sufficient evidence to show that the structure…was never the cell of a stylite, as had been previously assumed.” Instead, it may have been a fortified lookout, from which two or three soldiers, equipped with weapons and provisions, “could observe events behind enemy lines during a siege of the Acropolis and also receive messages from other individual fortifications not visible from the citadel.”

Reports of Stylite Monks

However, at least two travelers’ accounts, apparently unknown to Bouras, refer to the Olympieion’s later addition being used as a stylite monk’s refuge.

The first belongs to the painter Edward Dodwell, who, during his visit to Athens in 1805-1806, noted, “the brick building that rests upon the architrave of the two western columns of the middle range [of the Olympieion] is supposed to have been the aerial residence of a stylite hermit: it is three stories high, and about twenty feet long, and seven broad; and must have been erected when the temple was much more perfect…”

This testimony implies that the monk had lived on the columns sometime prior to his visit, by which time this local figure had become only a memory and fascinating historical fodder for Dodwell’s tour guide or informant.

However, Dodwell also provides evidence of a monk residing on the Olympieion during his own time. He reports that, while preparing to record the temple, he was approached by “an old Albanian woman, by name Cosmichi, who… passing by… [was] surprised at the unusual appearance of my camera obscura,” a large, portable, box-like imaging device then used as an aide in drawing and painting.

Dodwell quotes her as saying: “You know where the sequins are – but with all your magic you cannot conjure them into your box! For a black watches them all day; and at night jumps from column to column!”

Equally intriguing, Dodwell further reports: “She then proceeded gravely to assure me that the brick building upon the architrave was the repository of great treasure…and the habitation of [this] black.” Cosmichi’s remarks, although somewhat eccentric, indicate that a dark-skinned, perhaps Syrian monk or other hermit was, at that moment, living on top of the ancient temple.

A second account, just over a century later, is provided by another visitor and sometime resident, Alexander Wilbourne Weddell, Athens’ former American consul, who also describes his cherished experiences in Greece.

In a National Geographic Magazine article entitled “The Glory That Was Greece,” (December 1922), Weddell relates that one day he enjoyed a stroll to the Temple of Olympian Zeus:

“We took a seat on the base of one of the columns and looked up to its top. There, during a series of years, a long line of hermits had passed their nights and days until death brought them release. During my stay at Athens I was assured by an old Athenian that he remembered as a child visiting the precincts of the temple and carrying gifts of bread and fruit to the stylite who then dwelt on the column and who would let down a basket to receive the offerings of visitors.”

If the “old Athenian” of Weddell’s account is to be believed, at least one stylite monk had again taken up residence in the isolated structure on top of the Olympieion during the middle years of the 19th century.

Although Bouras was right that the substantial construction of the “stylite’s hut” seems less characteristic of an original stylite construction than of a possible defensive tower, this does not negate the fact, based on written testimony, that this lost historical monument was, at some point prior to Eustratiades’ 1870 diary entry, home to a series of stylite monks, who found “Hadrian’s Columns” a perfect perch, suitable to their spiritual needs.