The Lost Cities of Ancient Greece: Rediscovering a...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...

Buried in meters of volcanic ash, Akrotiri stands like a time capsule of Late Bronze Age Cycladic life

© Getty Images/Ideal image, ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

These days, shipborne visitors landing on Santorini quickly come face to face with its impressive geological and cultural past, as they disembark at the foot of its sheer volcanic cliffs. Three main archaeological attractions – the houses and streets of “Pompeii-like” Akrotiri, the ruins of the hilltop town of Thera and the island’s once-fortified towns and watchtowers – bear witness to three major phases in Santorini’s lengthy history: the prehistoric period, Geometric through Early Christian or Byzantine times and the medieval to early modern era.

Recurrent features in all these times were war and peace, as Santorini (or Thera) evolved from being a quiet island settlement, to a key maritime crossroads, a frequent target for pirates and, most significantly for its native population, a political plaything of great Western and Eastern powers

One of the platforms that provide excellent views over the archaeological site

© Vangelis Zavos/Ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

The earliest inhabitants of Santorini arrived during the Neolithic era, by at least the 4th millennium BC. Minimal, scattered traces of their architecture and pottery reveal they were very few in number, probably attracted by the natural abundance of the volcanically-formed island – freshwater springs, rich, arable soils and an encircling sea well-stocked with fish and other marine creatures.

Obsidian was also a much-desired volcanic product in Neolithic times, used for tool manufacturing, and early sea travelers may have looked to Santorini as a potential source of this valuable raw material, supplementary to the region’s main supply on nearby Milos.

As prehistoric seafaring expanded in the Aegean, more and more people migrated to Santorini, settling especially on a peninsula (“akrotiri”) at the southwestern end of the island, beside a large, south-facing bay that offered a naturally protected harbor.

After limited Neolithic occupation, the site known today as Akrotiri was reinhabited during the Early Bronze Age, from ca. 2,500 BC, and then went on to become an increasingly populated, prosperous and architecturally elaborate urban center and maritime hub through the Middle and early Late Bronze Ages (ca. 2,000-ca. 1,627 BC).

Leaping dolphins, in a wall painting from ancient Akrotiri, 17th c. BC.

© Vangelis Zavos/Ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

In the last quarter of the 17th c. BC, however, one or more earthquakes and minor volcanic eruptions were followed by a massive, far more devastating explosion that altered the island’s landscape and buried the town of Akrotiri beneath meters of volcanic ash. Thus was created one of the Mediterranean’s great archaeological sites, covering an enormous area of about 200,000m2 (20ha), which serves as a long-sealed time capsule of Late Bronze Age Aegean life.

Rediscovered in 1967 by archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos, Akrotiri has been steadily unearthed to the point where now about one hectare of ruins can be viewed beneath a vast protective roof. Removal of the thick ash layer revealed a remarkable prehistoric town: a sophisticated Cycladic culture heavily influenced by the Minoans of Crete, who likely were frequent visitors for trade with Akrotiri or even long-term or permanent residents.

Cultural affinities with Knossos and other Minoan centers include a light-spirited appreciation of nature and life, reflected in the more than fifty-eight colorful frescoes so far recovered and conserved. Among the extraordinary images are semi-tropical and spring landscapes, papyrus plants, dolphins, monkeys, antelopes, nearly-naked boxing boys, a young priestess, elegant ladies harvesting saffron, a fisherman holding up his bountiful catch and a fleet of ships arriving at port. Scenes from a naval battle may be allusions to an historical event and may show that life on Santorini was not always serene.

A portable ceramic oven/stovetop from Akrotiri, 17th c. BC (Archaeological Museum of Thera)

© Vangelis Zavos/Ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

Minoan architectural influence is seen in Akrotiri’s multi-storied buildings, some with suites of rooms with multiple doors, light wells and lustral basins. Water and waste were managed through a complex system of pipes and drains. Akrotiri’s excavations, led by Professor Christos Doumas since 1975, have also yielded tens of thousands of ceramic vessels and other artifacts of stone, metal and ivory. Even traces of wooden furniture, bed frames and basketry have been preserved within the site’s volcanic overburden.

Some thirty-five buildings stand beneath the modern roof, separated by a network of streets occasionally punctuated by small open squares. There are lavish public buildings such as “Xesti 3,” where a small golden ibex offering was found in 1999, and the imposing “Xesti 4” with its monumental façade of squared blocks and a painted procession of life-sized male figures that flanks its stepped entranceway.

Private residences include the “West House,” which features storerooms, workshops, a kitchen, a mill installation, a weaving room, a storeroom stocked with ceramic vessels, a bathroom and two possible bedrooms splendidly decorated with murals.

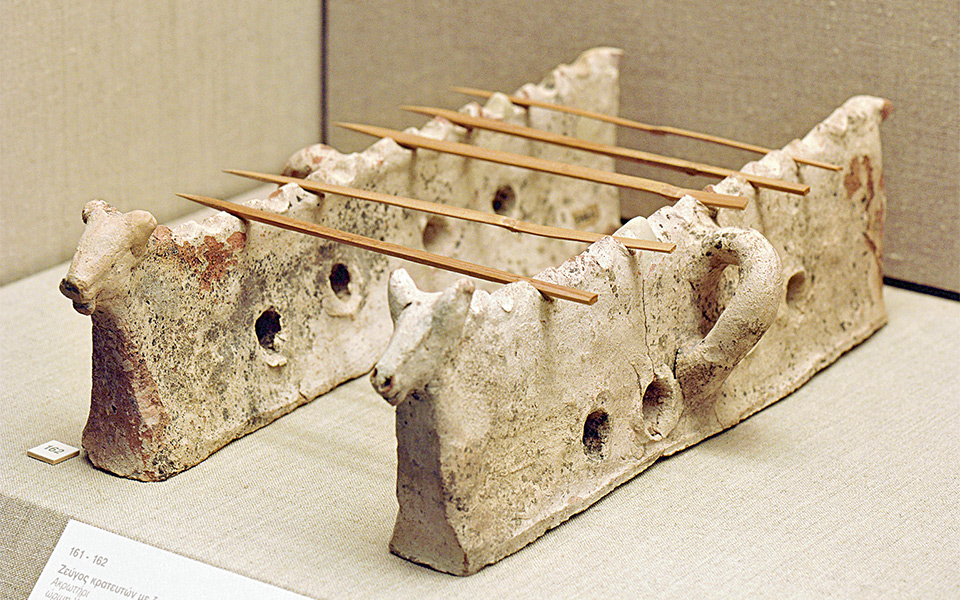

Firedogs or ''souvlaki trays'' with bulls-head finials, from Akrotiri, 17th c. BC (Archaeological Museum of Thera)

© Vangelis Zavos/Ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

The exotic subjects of some wall paintings and the many imported objects recovered at Akrotiri indicate the town enjoyed links with the outside world, including mainland Greece, Crete, other southern Aegean islands, Cyprus, Syria and Egypt. Its diverse population included traders, craftsmen, fishermen, farmers, shepherds, priests, priestesses and probably civic officials, at least some of whom were literate, judging from inscribed Linear A tablets discovered in “Building Complex D.”

To date, no royal palace or other evidence for a singular leader has been detected. Also lacking are any skeletal traces of the inhabitants themselves. This could mean they rightly took earlier seismic and volcanic events as signs of impending disaster, and thus were able to evacuate their doomed island before its final, cataclysmic eruption.

According to Doumas, further investigation outside the town – especially westward, where residents may have fled upwind to avoid smoke, ash and noxious gases – may still reveal burials or other archaeological clues regarding the ultimate fate of the exceptional and mysteriously absent Akrotirian people.

© Getty Images/Ideal image, ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

After the great Theran eruption, there is scant archaeological evidence for inhabitants on the island for many centuries. The historian Herodotus, however, reports that during this period, “…Theras…was preparing to lead out colonists from Lacedaemon [Sparta]. This Theras was of the line of Cadmus… and…held the royal power of Sparta… On the island now called Thera, but then Calliste, there were descendants of Membliarus…a Phoenician…[who had] dwelt [there]…for eight generations…It was these that Theras was preparing to join…to settle among…and not drive them out but claim them as in fact his own people.”

The presence of such mainland Greek (Dorian) colonists is well attested in the 9th and 8th c. BC by Geometric graves and pottery, which indicate the island’s new center of settlement was now on its east coast – on the slopes and summit of the mountain Mesa Vouno, overlooking the bays of Kamari and Perissa. It was here that the Geometric-through-Early Byzantine town of “Ancient Thera” was established.

Thera, named after its mythical founder, grew to be a far-reaching trade station, as shown by hundreds of excavated coins (6th c. BC) linking the town with Athens and Corinth to the west, and Rhodes and Ionia (western Anatolia) to the East. It also sent out its own colonists when, as Herodotus further reports, a seven-year drought (ca. 630 BC) led Therans to sail to Libya and establish the great port city of Cyrenaica.

Geometric-period vases are the earliest surviving works of art from Ancient Thera. (Archaeological Museum of Thera)

© Vangelis Zavos/Ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

Thera’s zenith came in Hellenistic times, during the 4th–2nd c. BC, when Alexander the Great’s rivalrous successors and later the Egyptian Ptolemaic navy exploited its port facilities as a strategic naval base. The fortified mountain-top town was reorganized with a more regular plan of paved, often stepped streets; affluent courtyard houses appeared; and religious/public life was enhanced with numerous temples, sanctuaries, gymnasia, Doric stoas (colonnaded walkways), a theater and/or council house (capacity 1,500) and, in Roman times, a bath complex.

German and Greek archaeologists, excavating since 1895, have unearthed a central marketplace and administrative center (agora); a major sanctuary honoring the Spartan deity Apollo Karneios; a large manmade terrace for hosting the annual Karneia festival; another sanctuary adorned with statues and relief-carvings, founded by the Ptolemaic admiral Artemidoros of Perge and dedicated mainly to Poseidon, Zeus and Apollo; a shrine for the Egyptian gods Serapis, Isis and Anubis; a natural grotto dedicated to Hermes and Hercules; and many dwellings, including an impressive residence thought to belong to the commander of the Ptolemaic fleet.

In early Christian times, Thera became the seat of a bishopric – the first bishop was Dioskouros (AD 324-344) – and several basilicas or smaller churches were soon established, sometimes on the spot of a previous pagan temple or shrine whose stones were reused for the new building. By the 8th or 9th c. AD, Thera had declined and was finally abandoned, perhaps partly as a result of renewed threats from the island’s volcano, such as the heavy barrage of pumice stone recorded as having fallen on the town in AD 726.

Serving dish; a representative example of Theran pottery in the Geometric and Archaic periods. (Archaeological Museum of Thera)

© Vangelis Zavos/Ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

Clay figurine dating to the 7th c. BC, with amazingly well-preserved colors. From the position of the arms above the head, it is believed to depict a woman mourning

© Vangelis Zavos/Ministry of culture and sports/General directorate of antiquities and cultural heritage/Ephorate of antiquities of Cyclades

In addition to the dangers they faced from volcanic activity, Santorinians were also plagued by seaborne bandits and covetous foreign powers. The story of Santorini in the medieval and early modern era represents a microcosm of the larger history of the Aegean islands during this period.

Many coastal communities, seeking greater security, moved inland after the mid- 7th c. Marauding Saracen (Arab/Muslim) pirates took control of Crete in the early 9th c. and began exacting tribute or “taxes” from the Cycladic islands. Through the following centuries, Santorini held little political or military significance and suffered greatly from poverty.

With the European Crusaders’ victory over Constantinople in 1204, the Venetians moved into the Aegean; Mark Sanudo took Naxos in 1205; and his relative Jaccopo Barozzi was initially granted “Santorini,” a name that recalls the conspicuous church of Santa Irini (Aghia Irini) in coastal Perissa.

As wealthy, adventuring lords divided up spoils from the Fourth Crusade, a feudal system was imposed in the Cyclades much like that in Europe; sea routes through the region were made safer; and maritime trade flourished. In Santorini, wine and cotton became profitable products. An aristocratic culture also developed. John IV Crispo, a governor of the Duchy of Naxos (1518-1564), is said to have fostered a lavish court life and tried to emulate locally the Western Renaissance.

The Kasteli of Emporio.

© Shutterstock

Despite such lofty aspirations, the Aegean remained fraught with risk. The Santorinians of the 13th through 17th c. increasingly found themselves on the fringes of a watery battlefield, caught between disputatious Byzantines, Venetians, Genoese, Catholics, Orthodox, Spaniards (Catalans) and Turks. Commonly heard on Cycladic streets and wharves were Greek, Italian and Turkish, while even the multi-lingual wording of contemporary legal documents reflected this rich mixture of cultures.

Pirates of diverse origin also continued to pose a threat, as they repeatedly raided Santorini and neighboring Aegean islands. Among them were the Barbary Pirates (from North Africa) and the infamous Barbarossa, Grand Admiral of the Ottoman Navy, in the 16th c. Albanian, Maltese and other Christian pirates – such as Hugues Creveliers, “the Hercules of the seas” – defied the Turks’ increasing hegemony in the 17th c., often aided by priests and monks who gave them provisions.

Francois Richard, a Jesuit, recorded at this time that Santorini had poor resources and suffered from severe drought when rainwater did not fill the islanders’ rock-cut cisterns. Moreover, he noted that, to counteract the danger of pirates, “most of the villagers’ houses or farmhouses, even churches and chapels, are underground. Thus, many families have over their roofs the fields, vineyards and gardens they cultivate.” Santorini’s wines, according to Richard, were exported to Chios, Smyrni, Chandakas (Heraklion) and Constantinople.

Panoramic view towards the island of Thirasia from the castle ruins at Aghios Nikolaos, Oia.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

The larger towns or important manors on Santorini were fortified by the island’s Venetian lords with stout, castle-like walls. These “kastelia,” equipped with gateways and “goulades” (watchtowers), existed at Skaros (or present-day Imerovigli), Oia (Castle of Aghios Nikolaos or Apanomerias), Pyrgos, Emporio and Akrotiri (Punta Castelli). Although heavily damaged by the earthquake of 1956, remains of these defensive structures are still visible today. They stood on strategic spots, difficult to attack from the sea, and served as nuclei for expanded settlement during later, more peaceful times. The best-preserved outlying watchtower is that of the Venetian Bozzi family in the island’s present-day capital of Fira.

Santorini’s fortunes greatly improved following the Greek War of Independence in 1821. Despite characteristically arid soils and few fresh water resources, agriculture and industry developed and commercial shipping flourished through the 19th and early 20th c. Before steam ships eclipsed sailing vessels in the late 1800s, Santorini possessed one of the largest merchant fleets in the Aegean, while Oia came to be known as “the village of the captains.”

The devastating 1956 earthquake severely altered the island’s upward course; many homes were destroyed, lives were losts and livelihoods were wiped out. The people of Santorini once again returned to poverty and hardship. However, since the economic resurgence of the 1970s, Santorini has, with the help of its unique history, stunning geology and burgeoning wine and tourism industries, now reached new heights of world-wide popularity as a vacation destination.

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...

Beneath the busy streets of modern...

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

A major restoration project is bringing...