Sacred Summits: Greece’s Ancient Mountain Sanctuaries

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...

The 1908 "Xylothravstis" (Wood Breaker) statue located opposite the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens covered in snow.

© Myrto Papadopoulos

February of 2021 saw one of the biggest snowstorms of recent years sweep over Greece. Dubbed “Medea” it brought snow even to the center of Athens, creating otherworldly scenes as the Acropolis Hill and other familiar landmarks were blanketed in white.

While heavy snowfall is a regular feature in winter time for northern regions of the country, where it is not uncommon for temperatures to fall below freezing, it is a relatively infrequent phenomenon at lower elevations and along the coastal regions.

Nevertheless, even in Attica, Athenians are no strangers to winter snow which will usually settle at least a few times each winter on the mountains surrounding the city.

The Acropolis Hill blanketed in snow on February 16, 2021

© Reuters / Alkis Konstantidis

But what was winter like for the ancient Greeks? And did it ever snow?

Scholars have long assumed the climate of ancient Greece (1st millennium BC) to have been broadly similar to today’s mild Mediterranean climate of long, hot summers, and short, relatively mild winters.

In ancient Greek art, notably in statues and vase paintings from the 5th and 4th centuries BC, both men and women are often depicted wearing simple, loose-fitting clothing, evocative of warm, dry weather.

Even so, snowfall in winter, while probably infrequent, was not altogether unknown. When confronted with such cold, wintry conditions, ancient Greeks would have donned a cloak called a himation (ἱμάτιον), a single, large rectangular piece of thick woollen cloth, draped over the left shoulder and wrapped tightly around the rest of the body.

In ancient Greek literature, the mention of snow or extreme cold appears in several prominent texts. Among them, Hesiod’s Works and Days (536–544), a didactic poem composed around 700 BC, offers some practical advice for keeping warm in the cold winter months:

At that time wear, as I bid you, something that will

shield your skin,

a soft cloak and a tunic that reaches to the feet.

You must weave thick wool on a thin warp.

Wear this, and the hairs will not bristle,

standing on end all over your body.

As for your feet, fasten onto them tight-fitting boots

made from the hide of a slaughtered ox.

Make them snug with felt on the inside.

When the frost comes around in due season,

stitch together the skins of first-born goats

with the sinew of an ox.

Left: A Greek youth named Kleonikos wearing a himation robe. From the Gymnasium at Eretrea, Euboea, 1st century BCE. (National Archaeological Museum, Athens). Right: Statues at the "House of Cleopatra" in Delos depict a man and woman wearing the himation

© Left: Mark Cartwright - CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 / Right: CC-BY-SA-3.0

In this passage from the Odyssey (19.204–209), Homer describes snow melting as a simile for Penelope weeping for her long-lost husband, Odysseus:

Penelope wept as she listened, for her heart was

melted. As snow melts away

upon the mountain tops when the winds

from the South, East, and West have breathed up it

and thawed it till the rivers run full with

water, even do did her cheeks overflow with tears for

the husband who was all the time sitting by her side.

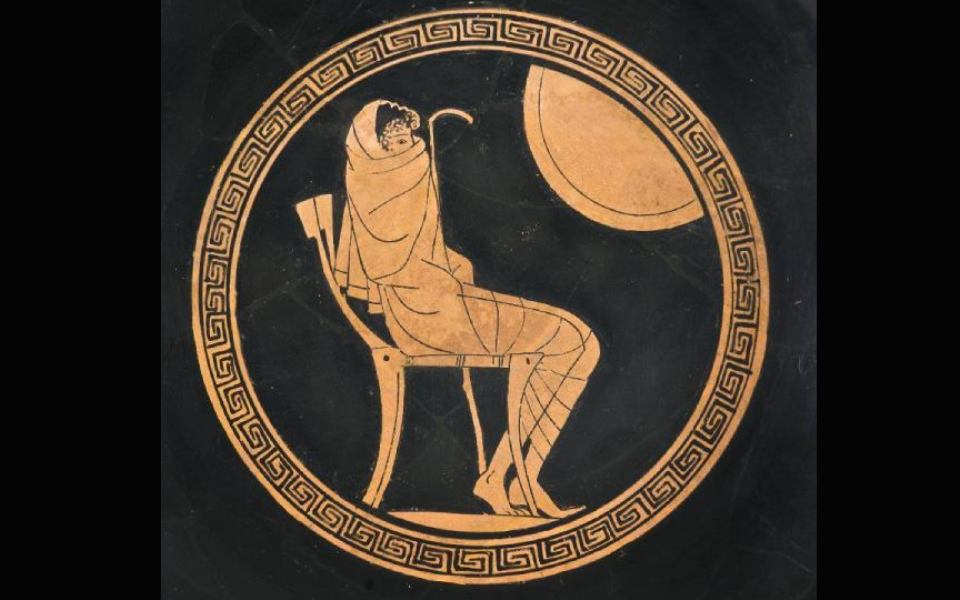

Sitting Achilles wrapped in a himation, depicted on a greek kylix from ca 500 BC.

© Margareta Sjöblom 1988 / Public domain

In Greek mythology, Chione (or Khione – from the Greek χιών, “snow”), was the daughter of Boreas, god of the north wind and “bringer of cold winter air.” She appeared as a snow nymph from Thrace – a minor goddess, albeit vain and conceited on account of her stunning beauty.

She claimed her attractiveness and charm rivalled that of Artemis, goddess of the hunt and twin sister of Apollo. Outraged, Artemis sought retribution and killed her with an arrow.

Her father’s name, Boreas, is the root of the adjective “boreal”, meaning “(far) northern” (e.g. boreal climate). The ancient Athenians believed serpent-tailed Boreas dwelt in a cave on Mount Haemus, high up in the Balkan Mountains. He blew cold wind in the winter months, impregnating the whole land of Attica, bringing forth flowers in the spring.

During the Persian Wars, the Athenians successfully invoked Boreas to destroy King Xerxes’ fleet off the coast of Pelion (480 BC). In gratitude, they founded a sacred precinct of Boreas on the banks of the River Ilissos in Athens.

In another tradition, Chione was the daughter of the Oceanid Callirrhoe (“beautiful flow”), an ocean nymph, and Nilus, one of the Potamoi (river gods) of the Nile. She was raped by a mortal and transformed into a snow cloud by Hermes.

While the depiction of snow and extreme cold seldom appears in ancient Greek literature and art, it is easy to imagine the ancients themselves being awe-struck at the otherworldly beauty of snow blanketing their sacred temples and monuments. And whenever Boreas whips his tail today and causes snow to settle even in central Athens, there is something timeless about seeing the very same monuments covered in snow.

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...

A major restoration project is bringing...

Cultural leaders reflect on Thessaloniki’s layers...

Before passports and package tours, pilgrims...