During events that shaped the identity of modern Greece, these poets stepped up to give voice to the collective spirit.

The poet Katerina Anghelaki Rooke, in her “Notes on Modern Greek Poetry,” wrote of Giorgos Seferis that “He traced the itinerary of the Greek man, who, like a new Argonaut, sets out not to find the golden fleece but his Greek identity.” It was a quest Rooke believed was shared by many: “… the poet… like a soothsayer or like a rhapsodist, like an historian or a psychoanalyst, a revolutionary or a conservative, was always the one who was trying to define, through his poetry, the position of a Greek soul in the modern world.”

Modern Greek poets have carved a place for the Greek soul, while also shaping the modern Greek experience. Poets have been on the front lines of events that have shaped the identity of modern Greece and those that have shaken it to its core, stepping up repeatedly to give voice to the collective spirit when it’s been needed most. Throughout Greece’s brave and turbulent history, it has been this way, even pre-dating the emergence of the modern Greek state: Dionysios Solomos’ Ὕμνος εἰς τὴν Ἐλευθερίαν” – “Hymn to Liberty”- served to inspire courage long before the War of Independence was won, and only later was set to music and adopted as Greece’s National Anthem.

Poetry continued to serve the Greek people throughout periods of darkness. Yannis Ritsos’ “Epitaphios,” honoring a victim of the Tobacco Workers’ strike of 1936, circulated widely before it was banned and burned. During the Nazi occupation, Angelos Sikelianos’ recitation of his work “Palamas” at the funeral of Kostis Palamas (the poet who wrote the Olympic hymn) blossomed into an expression of resistance that overtook the crowd, culminating in the singing of Greece’s National Anthem. Meanwhile, Nikos Engonopoulos’ poem “Bolivar” served to fuel Greek resolve in the face of Nazi oppression. At the funeral of Giorgos Seferis in 1971, in a powerful display of opposition to the military dictatorship of 1967-1974, a crowd of thousands joined in singing Seferis’ banned poem “Denial,” which had been set to music years earlier by Mikis Theodorakis.

The connection between the world of Homer and the contemporary paradise of archaeological treasures and sparkling beaches that today define Greece in the eyes of many can sometimes be elusive. Works of these six modern Greek poets resonate with the elemental, inviolate integrity of the Greek spirit, illuminating the continuity of the Greek experience through the ages.

Cavafy photographed in Alexandria.

Constantine Cavafy (Alexandria, 1863 – 1933)

W. H. Auden, as noted by Edmund Keeley, remarked on the distinctive quality of Cavafy’s voice, unmistakable in any language. Cavafy led a quiet life; his ambitions flourished in the cultivation of a rich inner world of intellect and palpable sensuality, felt in the intimate works for which many of his most ardent fans adore him. His emotionally vulnerable poems, such as “Comes to Rest,” “Half an Hour,” and “He Swears” evoke poignant moments of universal relevance so easy to identify with, particluarly in the reflective state that they inspire.

Cavafy belonged to the well-established Greek diaspora in Alexandria; a sophisticated relationship to his Greek identity comes through in his familiarity with history, so profound that it sometimes takes a wry, ironic turn. In To Have Taken the Trouble, it’s not an Agamemnon or an Alexander we meet, but rather Zabinas, Hyrkanos and Grypas. These rivals for power in Antioch are seen through the cynical eyes of a civil servant who is by no means averse to using the privileged information he has on Kakergetis (the ‘Malefactor’) of Alexandria, where he was previously posted, in order to secure a comfortable position.

Cavafy also scoffs deftly at the Spartans in his poem In the Year 200 BC, on account of their refusal to participate in any campaign they did not lead. This was why Alexander, in an inscription accompanying spoils of victory from the battle of Granicus that were sent to Athens, made such a point of excluding them: ‘Alexander the son of Philip and all the Greeks except the Lacedaemonians from the Barbarians who dwell in Asia.’

For the strength and virtues of Hellenism itself, and – perhaps especially as a Greek of the diaspora – above all for its unity, he has nothing but reverence, as he expresses in his work “In the Year 200 BC”:

“We the Alexandrians, the Antiochians,

the Selefkians, and the countless

other Greeks of Egypt and Syria,

and those in Media, and Persia, and all the rest:

with our far-flung supremacy,

our flexible policy of judicious integration,

and our Common Greek Language

which we carried as far as Bactria, as far as the Indians.

Talk about Lacedaimonians after that!”

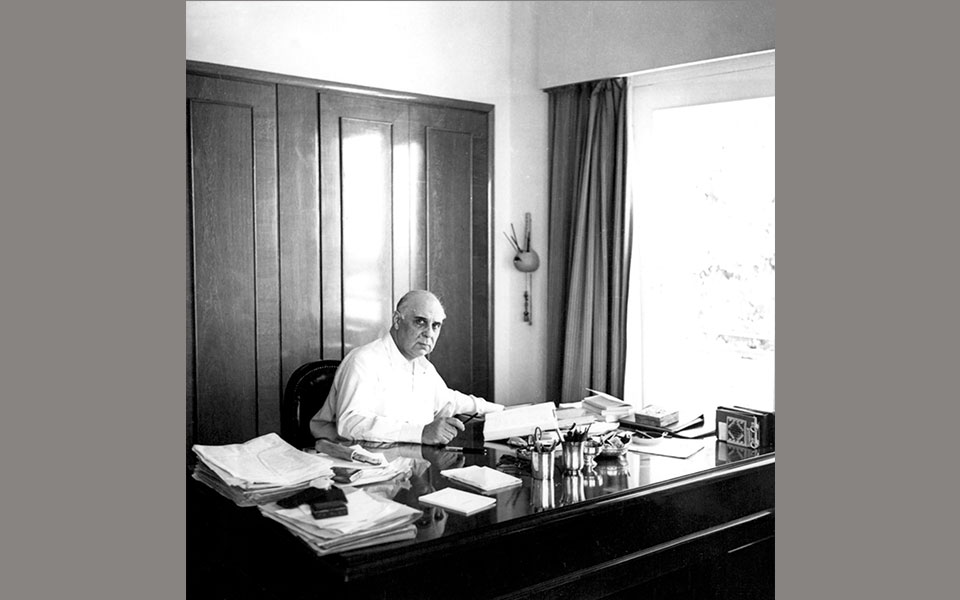

Giorgos Seferis at his desk in his office in Beirut.

© "Giorgos Seferis" Photo Archives / National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation

Giorgos Seferis (Smyrna, 1900 – Athens, 1971)

Giorgos Seferis, born in Smyrna, educated in Paris, and resettled in modern Greece along with over a million others following the 1922 catastrophe of Asia Minor, embodies an exploration of Greekness that is both his own personally, and that of a group of artists across all disciplines that came to be known collectively as “the Generation of the ‘30s.”

Seferis is as comfortable in the monumental world of history and myth as he is on the summer streets of contemporary Athens: “In the Manner of G. S.,” with its memorable beginning: “Wherever I travel, Greece wounds me,” they effortlessly intertwine. There’s not the barest trace of pretension in his references to the lands of the centaurs and of Agamemnon; they’re as much a part of the landscape of his psyche as are Syntagma Square and Omonia Square.

He conjures the drama of Greece’s ancient past, both of nature and of myth, with mastery in “Mythistorema”: twenty-four short poems inspired by the Odyssey. An on-site experience of the ancient world inspired The King of Asini, a work conceived during Seferis’ wanderings around the ancient acropolis of Asini in the 1930s, while it was being excavated by his friend, Swedish archaeologist Axel Persson. In this poem, the narrator speaks of a king who was once “forgotten by all, even by Homer, only one word in the Iliad, and that uncertain” while this same unnamed speaker gazes out at the view the monarch once commanded, and, as the poem poignantly concludes, “sometimes touching with our fingers his touch upon the stones.”

Seferis served Greece on an international level both through poetry, as the first Greek recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature (1963), and through diplomatic service, with postings in London and countries throughout the Middle East; he concluded his diplomatic career as Royal Greek Ambassador to the United Kingdom, retiring in 1961. In 1967, Greece fell to a military dictatorship; in response to this oppressive regime, Seferis ceased to publish his works, and issued a statement in 1969, broadcast by the BBC: “…. It has been almost two years now that a regime has been imposed on us which is totally inimical to the ideals for which our world – and our people so resplendently – fought during the last world war….” He did not survive to see the Junta fall; while still under the dictatorship, Athens “vibrated with the spirit of freedom that overflows in his poetry” at the funeral of Seferis in 1971, as a crowd of thousands sang his banned work “Denial,” in a spontaneous expression of resistance.

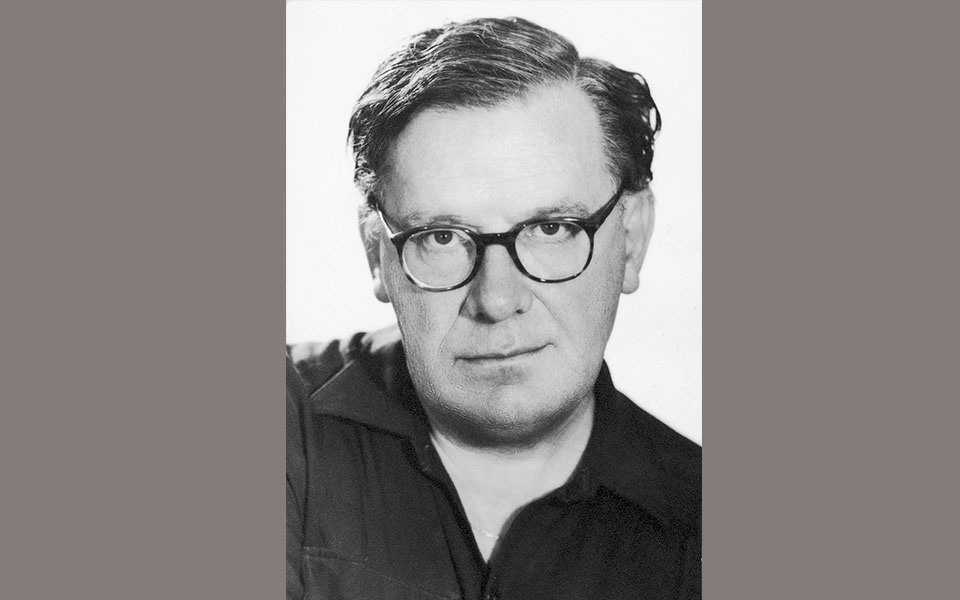

Nikos Engonopoulos

© From the archives of Errietti Engonopoulos.

Nikos Engonopoulos (Athens, 1907 – 1985)

Greece’s best known surrealist is famous outside the country chiefly for his paintings, which, in their profoundly Greek orientation, provide a rich context for his poems. He studied with three influential artists of the day, including Fotis Kontoglou, master of Byzantine painting. In the surreal landscapes of Engonopoulos’ paintings, visual elements of Greek identity in all its complexity coalesce: historic and mythological figures and allusions, architectural elements from both the ancient world and the Byzantine era, and the Greek seas and skies.

Elements of Greece are also woven into the dream-like landscape of the subconscious in which his poems unfold, such as in ”On Elevation.” He is most resolutely Greek in spirit; Engonopoulos, who fought on the Albanian front in the Greco-Italian war, also served the Greek cause through poetry, much as Solomos had. His poem Bolivar, celebrating the revolutionary hero who liberated much of South America from Spanish domination, incorporates the consciousness of Greece’s struggles against oppressors; written after the Nazi occupation of 1941, the poem was circulated in secret, to be read at meetings of the resistance. This ennobling spirit of resolve was replaced by a growing sense of despair by the time of the Civil War which followed WWII; Engonopoulos’ work “Poetry 1948” is eloquent in its expression of the futility of writing anything at all.

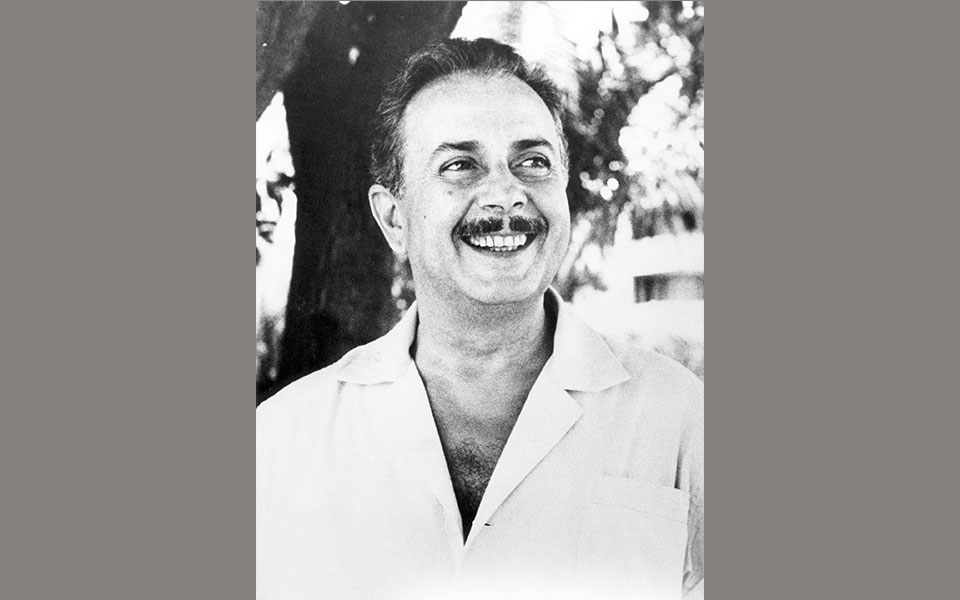

Yannis Ritsos

© From the "Yannis Ritsos" archives, courtesy of Eri Ritsou.

Yannis Ritsos (Monemvasia, 1909 – Athens, 1990)

The works of the prolific Ritsos – who wrote over a 100 published collections of poems, plus theater and prose and many unpublished volumes – capture both an eternal essence of Greekness and the exigent concerns of the Greek reality of his times. In the monologues of “The Fourth Dimension,” such figures as Agamemnon, Iphigenia and Orestes speak to us across the centuries about their introspective concerns, while in “Penelope’s Despair,” the poet renders a momentous mythical encounter known to all with intimate, relatable poignance.

The most compelling expressions of Greekness in Ritsos’ works are in anthemic works that celebrate the indomitable Greek character, itself tied inextricably to the Greek land and the Greek light. This is certainly present in the civil war-era work, “Romiosini,” whose very title shouts “Greekness.” Romiosini is another name for medieval Hellenism, based on the fact that the Byzantine Empire saw itself, in essence, as the heir of Rome.

Ritzos’ earlier work “Epitaphios” honors a tragic and polarizing episode in the social and political landscape of interwar Greece under the Metaxas regime. When the Tobacco Workers strike in Thessaloniki of May 1936 escalated into violence, the image of the mother of Tassos Tousis bent in grief, Pietà-like, over the body of her dead son compelled Ritsos to work day and night, by his own account “… often sobbing like a Maniot lamenter,” to write the first section of Epitaphios, which was published at once. A full version followed, all of which were sold but for the copies seized by the regime and burned at the Temple of Olympian Zeus, along with other works deemed subversive – a dark testament to the poem’s galvanizing power.

“Epitaphios” spoke to the core of Ritsos’ political identity as a dedicated Communist. He continued to serve as a voice of resistance in the turbulence to come. During the Civil War, he was exiled to a prison camp on the island of Makronissos along with other leftists and artists, including Mikis Theodorakis. Ritsos later sent him “Epitaphios.” Theodorakis credited the experience of composing a score for it – creating something positive from the lasting trauma from his experience on Makronissos – as transformative. Manos Hadjidakis orchestrated the work, with Nana Mouskouri singing, and other versions followed, including one performed by rebetiko singer Grigoris Bithikotis, whom Theodorakis had met on Makronissos, and the legendary bouzouki player Manolis Chiotis, and another version performed by Manolis Chiotis, with vocals by Mairi Linda.

Ritsos was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1975, and was awarded the Lenin Prize in 1977.

Odysseas Elytis

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Odysseas Elytis (Heraklion, 1911 – Athens, 1996)

“May I be permitted, I ask you, to speak in the name of luminosity and transparency?” So began Odysseas Elytis’ Nobel lecture upon winning the 1979 prize in Literature, by evoking the radiant essence of Greece.

In Elytis’ richly descriptive and accessible works, the elemental glory that is Greece washes over the reader in sensuous imagery of green seas and mountainous land, sea-urchins, cicadas, jellyfish, intoxicating birds thriving under a radiant sun, and trees laden with pomegranate and quince. The works transcend the sensual; Greece’s tangible beauty represents an ideal worth pursuing. In the words of Anghelaki-Rooke, Elytis, “…., through a mystification of the ‘sparkling’ Aegean, saw a natural and eternal value, which was there to sustain the Greek soul: all this light to be shed in the dark path of our contemporary world!”

Odysseas Elytis’ personal experiences serving on the Albanian front during the Greco-Italian war inspired his “Heroic and Elegiac Song for the Lost Second Lieutenant of the Albanian Campaign,” in which the young man and the Greek land itself merge into the embodiment of the eternal valor of the Greek spirit:

“… What a proud map his naked chest

Where freedom, where the sea resounded…”

The noble and the heroic in the Greek spirit and in life itself is the theme of his most prominent work, the poetic cycle “Axion Esti.” The title, repeated within the body of the work, references another aspect of Greek identity; axion esti – “worthy it is” – appears frequently in the divine liturgy of the Orthodox Church. This cycle of three sections – “Genesis,” “The Passions’‘ (Psalms, Odes, Readings), and “Gloria” or “Praised Be” – begins with the miracle of creation, then expresses the challenges and afflictions of life, and concludes with the praise of life in its bountiful pleasures, so worthy indeed of its struggles.

Born Odysseas Alepoudellis, his adopted name Elytis is composed of allusions to the concepts he valued most and explored in his works; “El” refers to “Ellas” (“Greece”), to freedom (“eleftheria”), to beauty and erotic sensuality as personified in myth by Helen (“Eleni”), and to hope (“elpida”).

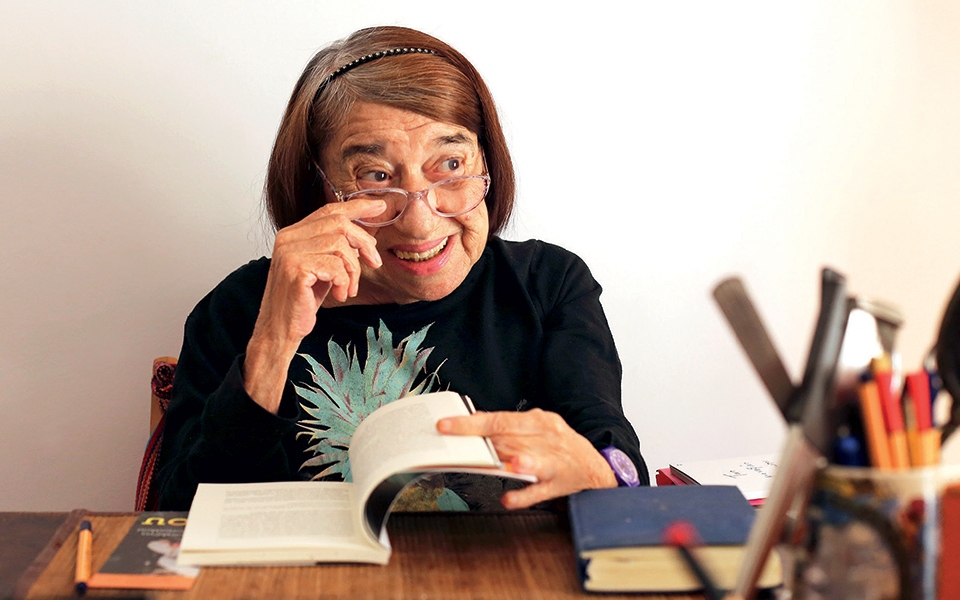

Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke

© Nikos Kokkalias

Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke (Athens 1939 – 2020)

Anghelaki-Rooke’s voluptuous, sensual poetry unites the body, the soul and the mystery of existence. Her poetic voice had an early start; she published her first poem, “All Alone,” at seventeen, in the magazine New Era, with the encouragement of her godfather, Nikos Kazantzakis. By her twenties, she was well on the way to being an established poet, as well as a translator of literature from Russian, English and French into Greek.

Anghelaki-Rooke was one of the best known poets of the group known as “the Generation of the 70s,” united by a repressive era in modern Greek history. In contrast to Seferis, who refrained from publishing under the dictatorship, she responded to the censorship of the 1967-1974 regime by working with a group of other young poets and the translator Kimon Friar on an anthology. She also published her own second volume of poetry, Poems 63-69, in 1971. In an interview, she addressed the spiritual challenges of the era: “What makes this generation the generation of the ‘70s is that Greece experienced a second civil war, 30 years after the first one…. Our second civil war was a division between who was cooperating with the Junta and who was not. I cannot even breathe when I remember those days.”

Her poetry, however, expresses more eternal concerns. Professor Karen Van Dyke captures Anghelaki-Rooke’s universal relevance beautifully: “Hers is a poetry of flesh, indiscretion, and the divine all rolled into one. For Anghelaki-Rooke, the body is a passageway anchoring the abstract metaphysics of myth in the rituals of everyday life.” In “Heat,” she illuminates the profound connection through a distinctively Greek experience, evoked through the palpable imagery of an August afternoon, from the stillness of the violently sizzling afternoon heat to the relentless cicadas and the call, over his megaphone, of the watermelon man.

For Further Reading

A Century of Greek Poetry 1900 -2000

Selected and Edited by Peter Bien, Peter Constantine, Edmund Keeley, Karen Van Dyck

Cosmos Publishing, 2004

The Essential Cavafy

Selected by Edmund Keeley, with Translations by Edmund Keeley and Phillip Sherrard, Notes by George Savidis

Ecco Press, 1995

Modern Greek Poetry

Translation, Introduction, Commentaries, and Notes by Kimon Friar

Notes on Modern Greek Poetry

Katerina Anghelaki Rooke

The City, the Spirit, and the Letter: On Translating Cavafy

André Aciman