Ancient Greece, renowned for its extraordinary achievements in philosophy, art, and politics, was also home to some of the earliest recorded ghost stories. From the epics of Homer to the tragedies of Aeschylus, Greek literature brims with chilling accounts of spirits who haunted, cursed, and reached across the threshold of death to contact the living. Whether appearing as vengeful specters or unburied souls seeking release, these ghosts held a powerful and unsettling presence in Greek thought and storytelling.

In the spirit of Halloween, we’re uncovering the layers of myth and history to explore some of these eerie tales—stories of lost souls, revenants, and dark rituals that haunted the ancient Greek world. Join us as we venture into the shadowy underworld that continues to stir curiosity, unease, and fascination to this day.

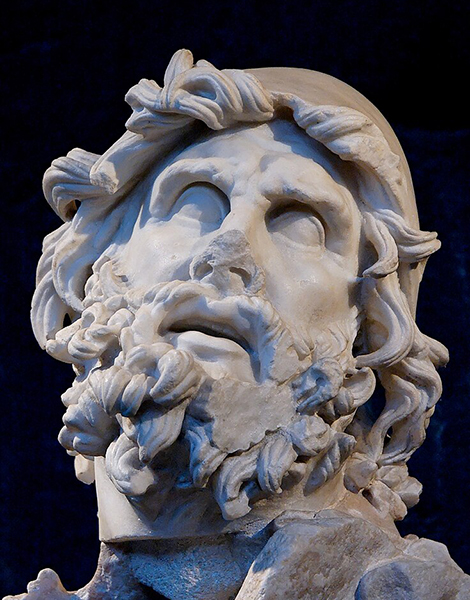

Odysseus and the Ghosts of the Underworld

In Book XI of Homer’s “Odyssey” (c. 8th century BC), Odysseus—the indomitable hero longing to return home from the Trojan War to his island kingdom of Ithaca—embarks on a harrowing journey to Hades, the land of the dead. This grim undertaking is instigated by the enchantress Circe, who urges him to seek guidance from the ghost of the blind prophet Teiresias on how to reach Ithaca. Following her counsel, he sails to the “land of the Cimmerians”—thought to lie in the Pontic-Caspian steppe—where he performs a gruesome ritual to summon the spirits.

In a haunting scene, Odysseus digs a trench, fills it with blood from sacrificial animals (a ram and a ewe), and adds milk, honey, and wine to pacify the restless dead. The spirits gather quickly, drawn by the vitality of the blood, each one desperate for even a fleeting taste of life. Among them are figures from his past: his deceased mother, Anticlea, whose mist-like form slips agonizingly through his fingers as he tries to embrace her, and his fallen crewman, Elpenor, who pleads for a proper burial so he may finally find peace.

Through Odysseus’s encounter, we catch a glimpse of a Greek worldview where the souls of the dead linger close to the living, especially those denied proper rites. Burial was not merely a ceremonial act but an essential ritual to bring peace to a spirit; without it, the dead remained restless, waiting for any opportunity to re-enter the realm of the living. Death seemed but a thin, fragile curtain—one that could be breached by the right ritual or by neglecting one’s sacred duties to those who had passed beyond.

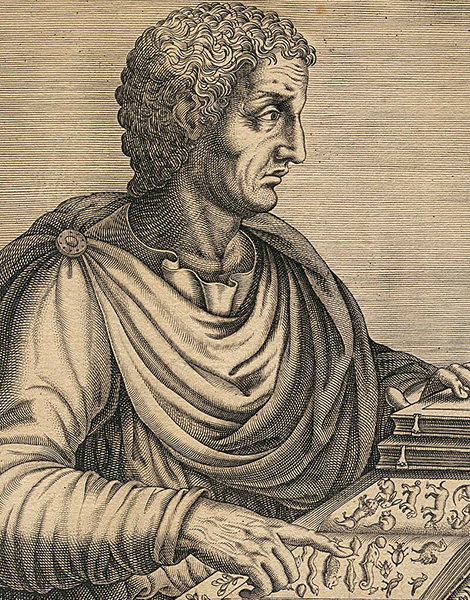

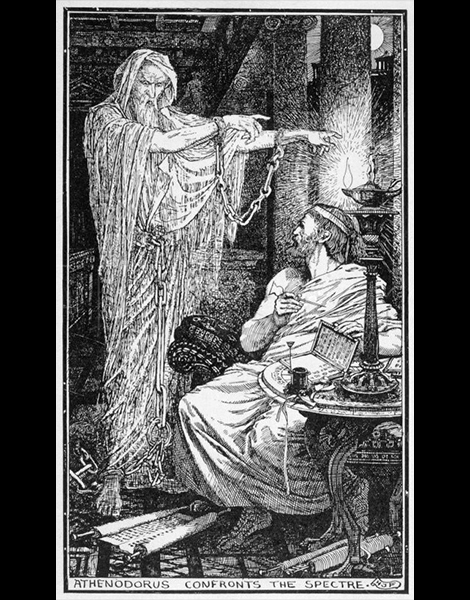

The Philosopher and the Haunted House

Athenodorus Cananites, a Stoic philosopher of the 1st century BC, was renowned for his disciplined mind and skepticism of superstition. Yet, as recorded by the Roman writer Pliny the Younger (61 – c. 113 AD), Athenodorus once found himself caught in a chilling encounter with a ghost.

While seeking affordable lodging in Athens, the young Athenodorus learns of a suspiciously inexpensive mansion rumored to be haunted. Intrigued rather than deterred, he seizes the chance and moves in. On the first night, he settles in for quiet study, unshaken by tales of eerie disturbances. But soon, the sound of clinking chains reverberates through the silent house, growing louder until a spectral figure—a pale, skeletal form bound in chains—appears in the doorway, beckoning him to follow.

Remarkably, Athenodorus does not flee. Instead, he follows the apparition to a spot in the courtyard, where it points before vanishing into the ground. The next day, he reports his experience to the city officials, who excavate the site and uncover a shackled skeleton. After giving the remains a proper burial, the hauntings cease. Like Elpenor’s plea to Odysseus, this story highlights the belief that failing to honor the dead with proper rites could doom a soul to restless wandering, awaiting release. Even for a skeptic like Athenodorus, reason alone was not enough to escape the pull of tradition and the haunting influence of the spirit world.

The Phantom Bride

The tale of Philinnion and Machates, as recounted by the 2nd-century AD Greek writer Phlegon of Tralles, takes place in the city of Amphipolis, Macedonia, during the reign of king Philip II (382–336 BC). Philinnion, a young woman whose life was tragically cut short, left her family heartbroken and distraught. Sometime later, a visitor named Machates arrives in Amphipolis and stays at her parents’ home. He is startled when a mysterious woman appears in his room late at night, bringing gifts and showing him deep affection.

For three nights, Machates shares his bed with this beautiful stranger, unaware of her true identity. When her parents discover these midnight trysts, they recognize the woman as their deceased daughter, Philinnion. The gifts she had been giving to Machates were her grave goods. Horrified, they confront her, breaking the spell, and Philinnion retreats to her tomb. Fearing her restless spirit might return, her parents – and the terrified townsfolk – burn her remains outside the city walls to prevent further hauntings.

Philinnion’s tale underscores the Greek fear of revenants—spirits that could force their way back into the land of the living. Her return serves as a reminder that, in ancient Greece, death was not a firmly closed door but a portal that could, under certain conditions, swing open. Some scholars consider this story as one of the earliest examples of a vampire-myth, especially when read in conjunction with the tale of another ghostly young woman who seduced the youth Menippos and fed on his blood, the Lamia of Corinth. Though the Greeks may have accepted such occurrences as part of fate or divine will, this story highlights the unsettling possibility that the dead might not always remain in their graves.

Necromancy and the Power of the Dead

In ancient Greece, communing with the spirit world was not always for solace or reunion. Necromancy—divination through communication with the dead—was a dark art that sought to access hidden knowledge from those who had crossed over. Derived from the Greek words for “corpse” (nekros) and “divination” (manteia), necromancy involved elaborate and often frightening rituals that summoned the spirits of the deceased, sometimes to seek revenge, deliver curses, or extract forbidden knowledge. This practice thrived in ancient Greece, especially near sites believed to be gateways to the underworld, such as the Oracle of the Dead at Ephyra—the famed Necromanteion of Acheron in northwest Greece.

Priests and practitioners would inhale noxious fumes believed to open a path to Hades, invoking chthonic (literally “beneath the earth”) deities like Hecate, goddess of witchcraft and magic, or Melinoe, a figure associated with restless spirits. Curses were often inscribed on thin lead tablets and buried with the dead, meant to carry messages to the rulers of the underworld. For the Greeks, these acts underscored their awareness of death’s proximity and the potent, dual-edged power it held—capable of revealing forbidden knowledge or enacting dark vengeance.

© Olga Charami

One such bizarre and macabre tale of necromancy comes from the writings of Apuleius, a philosopher and rhetorician of the 2nd century AD. In this story, a man named Thelyphron visits the Greek city of Larissa (Thessaly), where he is hired to guard the corpse of a recently deceased man on the night before burial. Alone with only a lantern, Thelyphron endures a tense vigil beside the body. During the night, a bird flies into the room, and as he reaches to catch it, he suddenly falls into a deep sleep.

At dawn, Thelyphron finds the body undisturbed, collects his payment, and prepares to leave. But just then, a mob accuses the widow of poisoning her husband. A necromancer is summoned to raise the dead man’s spirit, who, to the crowd’s shock, confirms his wife’s betrayal. Even more disturbingly, the ghost reveals that the “bird” was, in fact, a witch who hypnotized Thelyphron and stole parts of his nose and ears, replacing them with wax. Horrified by his disfigurement, Thelyphron flees, pursued by the mocking laughter of the crowd.

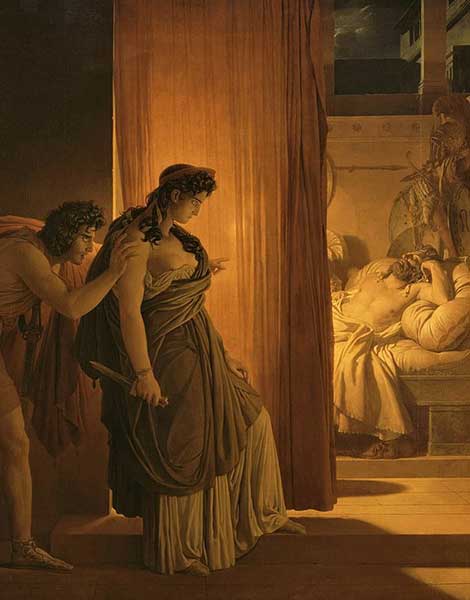

Vengeance Beyond the Grave

One of ancient Greece’s most chilling tales of vengeance from beyond the grave unfolds in Aeschylus’s “Oresteia,” a tragic trilogy of plays composed in the 5th century BC. The story begins with the return of the warrior king Agamemnon from Troy to Mycenae, where he is promptly murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, with the help of her lover, Aegisthus, as retribution for the sacrificial death of their daughter, Iphigenia. But Clytemnestra’s vengeance does not end with Agamemnon’s death. Soon after, their son, Orestes, encouraged by his sister, Electra, murders Clytemnestra to avenge his father, a violent act that shatters the family’s moral order.

From the underworld, Clytemnestra’s spirit summons the Furies—chthonic goddesses of vengeance who enforce divine justice—to haunt and relentlessly pursue her son. These terrifying figures, embodying pure rage, hunt Orestes across Greece, from the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi to the city of Athens, tormenting him for the crime of matricide.

The Greeks believed that spirits could haunt not only individuals but entire bloodlines, and Clytemnestra’s revenge reflects a cultural belief that moral breaches, especially within families, could spark catastrophic, intergenerational curses. For Orestes, the Furies’ relentless pursuit embodied the wrath of the dead, serving as a grim reminder to the living that moral transgressions could reverberate far beyond the grave. The boundaries between life and death were fragile, and vengeance, once summoned, could endure beyond time and mortality.

These ghostly tales from ancient Greece reveal a world in which the dead were rarely at peace, where spirits lingered just beyond sight, and the fragile veil between worlds could be pierced with a ritual or an unresolved grievance. This Halloween, as we celebrate our own fascination with ghosts and the supernatural, these ancient stories remind us that our curiosity about life beyond death is nothing new. The allure of the unknown transcends centuries and cultures, proving that even in our modern world, the shadows of Hades still call to us.