From pre-wedding sacrifices to the distinctly unsavoury concept of pederasty, attitudes to sex and marriage in ancient Greece, on the surface at least, appear completely alien to our own.

Marriage and reproduction were vital for the maintenance and continuation of ancient Greek society, and viewed as a matter of public interest. In fact, criminal proceedings could be made against men who married too late in life, typically after the age of 35, as well as against confirmed bachelors who stubbornly refused to get married. It was the duty of every citizen, therefore, to raise up strong, healthy, and legitimate children for the good of the state.

Ancient Greece was a deeply patriarchal society, where freeborn women were expected to be chaste and modest: “The greatest glory [for women] is to be least talked about among men, whether in praise or blame,” according to 5th century BC historian, Thucydides. As head of the family, decision making in the “oikos” (household) was down to the husband, and was rooted in the innate belief in male sexual dominance and female subservience.

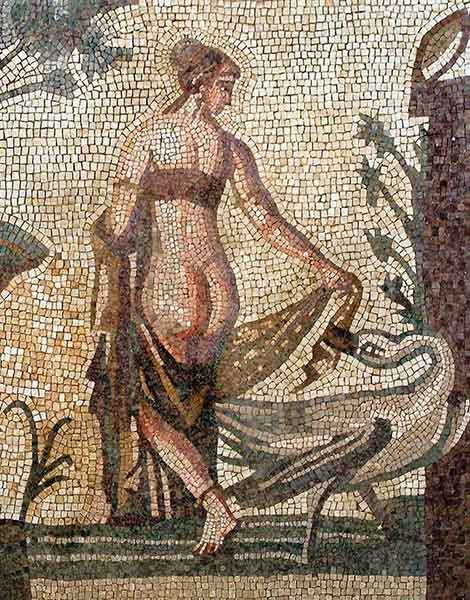

While sexual practices in ancient Greece may be shocking to our own, modern sensibilities, it’s important to remember that sex and marriage in ancient Greece ensured the fecundity of the family line, including the transfer of assets and property from generation to generation, especially among freeborn landowning elites. Wives were considered as instruments for bearing legitimate children, and marriage the “seedbed” of society.

© Public Domain

© Public Domain

Sex and sexuality

Attitudes towards sex in ancient Greece were deeply rooted in myth and religion, where sex was inextricably linked to the creation of the Universe, the gods, and the birth of humankind.

Hesiod described one of the earliest accounts of the creation story in his epic poem “Theogony” (or “Genealogy of the Gods”), composed towards the end of the 8th century BC. In his version, Uranus (Sky) mated with his mother Gaia (Earth), producing the “first generation” of 12 Titans, including Cronus and Rhea, and six monstrous giants – the cyclopes and the frighteningly weird Hecatoncheires (“100-handers”). Cronus and his sister-wife Rhea produced the first six of the Olympian gods, the “second generation,” including Hera and Zeus, who in turn produced Ares and Hephaestus, and so on.

Zeus, as the shape-shifting king of the gods, was notorious as the master of seduction, serial rape, and sexual oppression, of both gods and mortals, female and male. His seedy escapades spawned numerous illegitimate offspring (e.g., Helen of Troy, following his rape of Leda in the guise of a swan; Perseus, after he came to Danaë, an Argive princess, disguised as a “golden shower” of rain; and the Minotaur, after he morphed into a bull and abducted Europa). Zeus’ long-suffering wife Hera, despite her role as goddess protector of women, marriage and childbirth, was oftentimes depicted in Greek mythology as spiteful and jealous, enraged by her husband’s infidelity.

Laden with tales of incest, polygamy, and sexual violence, not only did the creation stories set the precedent for male sexual domination and the essentially submissive, reproductive role of women in ancient Greek society, they also shaped male insecurity about women. While it may be a bit of a stretch to think of ALL men in ancient Greece as sexual predators, during the Archaic and Classical periods (c. 750-323 BC), there was considerable power imbalance between men and women.

© Public Domain

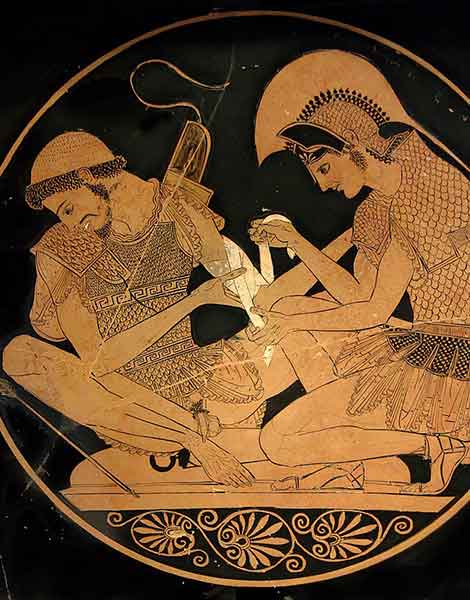

© Sosias Painter - Public Domain

Male bonding

Before exploring the role of marriage, it might be useful to consider the oft-discussed topic of male bonding, especially in the context of all-male drinking parties, “symposia,” which would often coincide with major religious festivals. During these celebrations, respectable freeborn men would gather to converse and amuse themselves, oftentimes in the company of “hetairai,” highly educated and expensive courtesans, trained in music, dance and poetry (akin to Japanese geisha women).

The most striking visual references to the goings-on at symposia can be found in the painted scenes on drinking cups (“kylikes”), depicting glimpses of graphic sexual behaviour. Their prevalence in the archaeological record – tens of thousands of Attic Red figure forms survive to this day – suggest they were a highly sought after decorative motif. Provocative scenes of group sex, romantic encounters between older men and younger boys (pederasty), and violent scenes of men beating women whilst simultaneously engaging in intercourse, shine a disturbing light patterns of ancient Greek sexuality.

Prior to marriage, freeborn males were expected to engage in sexual experimentation from an early age, including the use of prostitutes and household slaves. Pederastic homosexual relations, especially for the elite, may have been seen as a right of passage – relationships that were both educational and sexual in nature between an adult man, known as a “philetor” (“befriender”), and a young teenage boy (“kleinos,” meaning “glorious”). Homosexuality in ancient Greece was not stigmatised in the way that is in certain societies today. The formation of the famous sacred Band of Thebes, an elite military force made up of 150 pairs of male lovers, suggest that homosexual relations were openly encouraged as a means of reinforcing intense male bonding, vital for success on the battlefield – something that scholars refer to as the “hoplite mystique.”

An important aspect to consider here is the idea of sexual dominance: as long as the man having sex was dominant and not passive, he could do whatever he desired, asserting his authority over all subordinate layers of society.

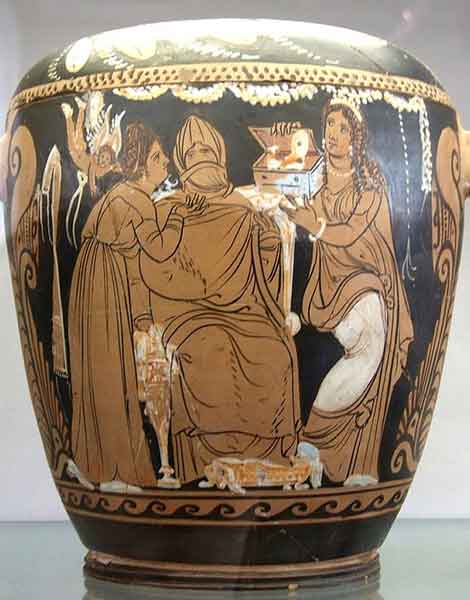

© Public Domain

The role of marriage

In stark contrast to their male counterparts, young freeborn women, especially in cities like Athens, remained strictly cloistered in the family home, and were carefully chaperoned when moving around in public. Virginity was a fundamental requirement of the marriage contract. In general, girls were married off the moment they reached puberty, between 14 and 16 years of age (the average age for men was 30), in order to begin the extremely dangerous process of child bearing and ensuring the male line of the family, her most important task.

In her book, “Birth, Death, and Motherhood in Classical Greece,” classical historian Nancy Demand asserts that Greek women bore children at an extremely early age, which was known to be dangerous by the men who controlled them, “at least in the extreme patriarchal form that it took in Athens and many other poleis” (city-states). Part of her argument is built on ancient medical writings, described in the “Hippocratic Corpus” as the “wandering uterus,” which was blamed for excessive emotion and hysteria. As such, the womb was believed to be the origin of all women’s diseases – “an animal within an animal,” according to Aretaeus of Cappadocia, a physician of the 2nd century AD. The only way to dampen the uterus was to have intercourse and get pregnant, the earlier the age the better.

Marriages were usually arranged by the fathers of the couple, often to increase the family’s finances and/or to improve their social standing; few, if any, married for love. Until a young woman was married, she was formally under the guardianship of her father. Once married, her husband became her “kyrios” (“master”). A dowry was given from the bride’s family to the groom, which was usually in the form of a lump sum of money or land and property. This was done to secure the financial stability of the wife in case the husband died, who reserved the right to select her next husband in the event of his death. The size of the dowry was likely a major factor in selecting a spouse in the first place, as well as her presumed fertility.

Once a marriage contract had been agreed between the two families, the father of the bride would formally announce the betrothal in front of a crowd of relatives, who served as witnesses: “I give you my daughter to sow for the purpose of producing legitimate children,” to which the intended groom would respond, “I take her.”

© Public Domain

© Public Domain

The marriage ceremony

A typical wedding event in ancient Greece took place over the course of three days – a preparation day, known as the “proaulia,” the ceremony itself, the “gamos,” and the giving of gifts on the third and final day, the “epaulia.”

Pre-marriage rituals, undertaken by the bride and groom, and performed on the proaulia, included sacrifices and dedications to the gods. Brides-to-be made sacrifices to the goddess Hera, a deity who represented the perfect wife, and to the virgin goddess Artemis, thanking her for her protection up until the age of marriage. Dedications were also made, including locks of the girl’s “maiden hair” and her girdle – a woven belt that she had worn since the onset of puberty, a symbol of her virginity.

On the day of the wedding, the gamos, the bride would take a ritual purity bath, attended by close female relatives. The bath water was drawn from a particular sacred source, depending on the location of the wedding – a nearby spring or sanctuary – and was thought to aid the couple in fertility.

Dressed in an ornate gown and and wearing a full face veil, the bride would then embark on a public procession through the streets with her groom to his “oikos,” her new home. The procession was either on foot or in a small cart, or, for wealthier families, in a chariot. The groom’s mother, waiting in the doorway and typically holding two lit torches, would welcome her new daughter-in-law to her home.

Feasting and merriment would then follow, including drinking, dancing and specific wedding songs, known as “hymen hymenaios.” Well-wishers would shower the couple with coins, dried fruits and nuts (in similar fashion to confetti), symbolizing prosperity and, most importantly, fertility. The last act of the night was the consummation of the marriage, which took place behind closed doors, while the guests continued the feasting and singing, which, according to some scholars, was to drown out the cries of the bride.

On the third day, known as the epaulia, gifts were given to the newly-wed couple, ensuring they had everything for their new family home, inlcuding furniture, cooking pots and pans, dinner plates, textiles and garments. The bride would then dedicate her ritual bath water from the gamos, carried in a “loutrophoros” (a water holder), to a nymph, in thanks for the marriage and in the hope of a good life ahead.