The Best Archaeological Day Trips from Nafplio

From Mycenaean citadels to ancient stadiums,...

The Mycenaean "Toumba" tholos tomb in the settlement of Dimini, below the Acropolis.

© Vassilis Makris

Approximately 11,500 years ago, humans, who until then had spent the majority of their existence as hunter-gatherers, learned how to cultivate the land, domesticate animals, and began establishing permanent settlements. This extraordinary transition is widely known as the Neolithic Revolution.

In the territory that is now Greece, this transition took place during the 7th and 6th millennia BC, and two of the most well-known Neolithic settlements are located in Magnisia, southeastern Thessaly: Sesklo and Dimini (approximately 15km and 5km away from the present-day city of Volos, respectively). Humans gathered and settled in advantageous positions on the hills surrounding this fertile land. To this day, contemporary settlements with the same names are filled with vegetable gardens and surrounded by vineyards and fields with almond, olive and pomegranate trees, as well as fragrant herbs.

As revealed by archaeological research, a prerequisite for the land’s continuous habitation from the Neolithic period until the end of the Late Bronze Age was the arable land and its connections with the Aegean Sea, thanks to proximity to the Pagasetic Gulf. Archaeological findings offer valuable information regarding the new organizational models that were developed, as people gradually began to procure their food in different ways. At the same time, they settled into permanent communities, developed new forms of architecture, and engaged in a range of other activities such as pottery making, which was used to manufacture clay vessels for storing and transporting food. Over time they established trade networks by exchanging pottery and food, and, in the later 5th millennium BC, gradually developed metallurgy.

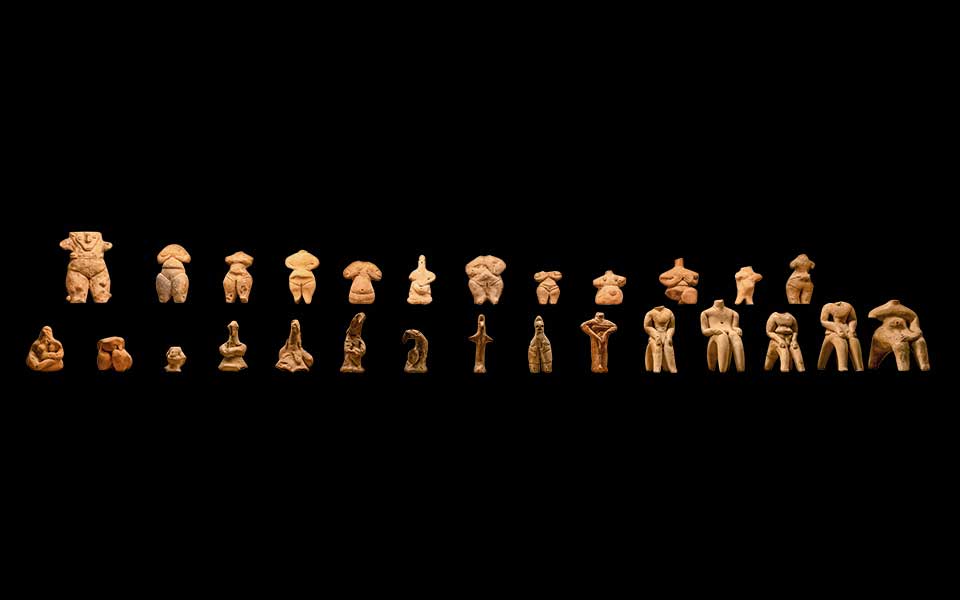

Clay figurines from the Neolithic ("New Stone Age") Era, from settlements in Thessaly. Athanasakio Archaeological Museum of Volos.

© Vassilis Makris

The prehistoric settlement of Sesklo, one of the oldest to be discovered in Europe, developed on the hill of Kastraki (referred to as “Sesklo A” or Acropolis) and in the surrounding area, southwest of Volos. Driving through the verdant route alongside the low hills, you can imagine what it would feel like to walk along the cobblestone path, the trail that connected the settlement with the sea (the present-day Golden Beach) thousands of years ago. A few minutes later, Sesklo surprises you. Two well-preserved cobblestone pathways lead visitors from the tree-lined entrance of the archaeological site towards settlements A and B, the area inhabited during the Early Neolithic Period, from the middle of the 7th millennium BC,to the Middle Bronze Age (1600 BC). Excavations at the site were carried out by archaeologist Christos Tsountas in the early 20th century, while in the 1960s, Dimitris Theocharis expanded the search to the flat slope on the western part of the hill, at “Sesklo B.” An interesting stratigraphy, with remains from the settlement’s habitation periods, is exhibited at the Athanasakio Archaeological Museum of Volos, in the room dedicated to Neolithic Civilization, which houses artifacts from all over Thessaly.

The Sesklo settlement is one of the most important Neolithic sites in Greece (end 7th millennium – 5th millennium BC), as it represents the so-called “Neolithic triad” (permanent settlement, agriculture, and livestock farming) and develops simultaneously on two levels (Sesklo A and Sesklo B). The expanse of the entire settlement has not been excavated entirely, yet a basic characteristic of its architecture is the diversity of the buildings and the variety of materials, as findings show stone foundations of houses, walls made of mudbrick, and structures made of clay, protected externally with large “upright stones.”

The House of the Potter is one of the most significant finds at Sesklo, as many vessels were preserved there from the fire that destroyed the settlement, c. 5200 BC.

© Vassilis Makris

Reconstruction of the Sesklo settlement floor plan, with architectural remains similar to those of the houses in the settlement. Athanasakio Archaeological Museum of Volos.

© Vassilis Makris

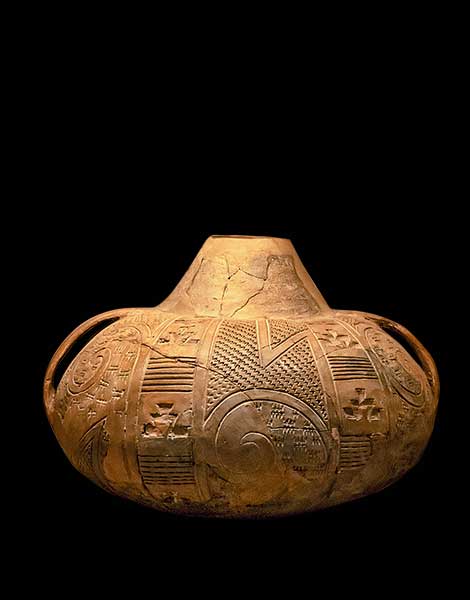

Clay pots, samples of written ceramic production in Thessaly, from Dimini (left) and Sesklo (right). Athanasakio Archaeological Museum of Volos.

© Vassilis Makris

The architectural ruins visitors can see today at the archaeological site of Sesklo (A and B) belong to the Middle Neolithic Period (5600 – 5200 BC), the peak period of the settlement. The houses have stone foundations, mudbrick superstructures, dual-pitched roofs covered with clay, wooden beams and a central opening for the smoke from the hearth to escape from. The diagrams on site, depicting plans of the settlements and architectural designs of the buildings, help us understand the organization of the spaces: the streets between the houses were narrow, and where there were larger openings, squares were formed.

One of the most interesting houses from the Middle Neolithic period on the Acropolis is the House of the Potter, where many vessels were preserved from the fire that destroyed the settlement in the late Middle Neolithic Period. We saw some of these and other interesting find during our visit to the Athanasakio Archaeological Museum of Volos. Among them, the pots for domestic use with characteristic red motifs, resembling flames, on the incised pottery (known as Sesklo pottery) stand out. These motifs were used to decorate the vessels, large storage jars for food, clay figurines, and tools for various tasks.

After 500 years, in the Later Neolithic Period* (4800-4500 BC), the Acropolis area of the site was inhabited once more, with the creation of a Megaron (a large hall) with three enclosures similar to those of Dimini. The area continued to be inhabited until the Middle Bronze Age. Some of the remains of houses that we see today on the Acropolis belong to this period, as well as the tombs found in both settlements (A and B).

The facade of the Athanasakio Archaeological Museum, Volos.

© Vassilis Makris

Arriving at the Acropolis of Dimini one cannot help but admire its prominent position, overlooking the entire Pagasetic Gulf. Built on a low hill, the settlement was founded in the middle of the 5th millennium BC, during the Later Neolithic Period. It consisted of 30-40 houses, and its inhabitants were engaged in agriculture, animal rearing, and fishing.

Dimini stands out from other Neolithic settlements due to its original architecture, featuring six concentric enclosures made of slate, upon which the houses were built. Even today, visitors can immediately discern the areas defined by each enclosure. With the assistance of the plan located at the entrance of the archaeological site, we identified the four points where these large walls were intersected by long and narrow passages leading to a central courtyard. There has been much discussion regarding the purpose of these enclosures. As the settlement was not fortified, the most plausible explanation is that they had been constructed to support the hill’s terrain, to delineate the living spaces and mark the areas for storage and for work.

A visit to the archaeological site may still provide an understanding, even today, of the architectural innovations that took place, but it cannot convey the progress that the inhabitants made here during the Middle Neolithic Period, when people realized what they could create with clay and developed the art of pottery. The ceramics of Dimini are characterized by vessels with dark-colored decorations, dominated by geometric patterns. One of the rarest finds from this time is the tight, almost closed ceramic kiln, indicating that the artisans were able to achieve and control high temperatures for firing their ceramics. Many of these engraved vessels are intricately crafted with thin walls, revealing an extraordinary level of technical skill. A collection of aesthetically pleasing utensils for storing liquids and solids, tools, as well as clay figurines from this period in Dimini are displayed in the Neolithic collection of the Athanasakio Archaeological Museum.

The construction of tools helped humans transition to agro-pastoralism in the mid-7th millennium BC.

© Vassilis Makris

Clay pots, samples of written ceramic production in Thessaly, from Dimini (left) and Sesklo (right). Athanasakio Archaeological Museum of Volos.

© Vassilis Makris

Approximately 300m from the settlement, in the flat area east of the hill and closer to the sea, we come across the newer settlement established by the inhabitants of Dimini during the Late Bronze Age (Mycenaean Period). According to samples of Linear B found in Pefkakia and Dimini, archaeologists identify this great palatial center as one of the three settlements of Mycenaean Iolkos.

The Mycenaean settlement, which flourished during the 14th and 13th centuries BC, consists of residences and an imposing architectural complex featuring two Megara (A and B, today protected by large canopies), two-storey buildings with white and red plaster, framed by peristyle courtyards, areas of worship, metalworking workshops, pottery workshops, storerooms, and more.

Among the most significant findings from this time are the two tholos tombs attributed to the kings of the settlement. Known as the “Lamiospito,” this tomb is located opposite the entrance to the archaeological site. Even though it is not accessible (you can view it only from the outside, from a distance of 20m), it impresses visitors as it protrudes from the hillside. The entrance to the interior was an opening measuring 3m in height and 1.90m wide, while the lintel with a large relieving triangle above it is visible. The dome was constructed with small, irregular limestone stones without any connecting material. The findings it yielded were not many, mainly consisting of bronze weapons, jewelry, and ivory objects, which are exhibited at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. The second large tholos tomb is called “Toumba” and is located on the hill with the Neolithic settlement, under House X. This tomb was found looted. You can visit the interior, even though it is not in good condition as the dome has collapsed. However, its proximity to the settlement enhances the experience of reliving the past in the archaeological site.

The term Period refers to a subdivision of the Neolithic Era.

Archaeological Site of Sesklo

Tel. (+30) 24210.951.72

Open daily except Tuesdays

08:30-15:00

Entrance €3

Archaeological Site of Dimini

Tel. (+30) 24210.859.60

Open daily except Tuesdays

08:30-15:00

Entrance €4

From Mycenaean citadels to ancient stadiums,...

At 1,160m, Metsovo blends preserved mountain...

A compact archaeological guide to the...

As its historic estates fade and...