There are two important and extremely interesting facts that we still don’t know about the Olympic Games of ancient times. The first is when exactly they began and the second is the performance of the winners in the various events.

The former may possibly be answered with the discovery of some ancient papyrus scroll or marble tablet engraved with the information we need to solve the mystery. The latter, however, will never be answered for the simple reason that there is no evidence to be found regarding athletes’ records. The process of recording time and performance was of no interest back then – not to the judges, the coaches or even to the athletes themselves – as a means of gauging their improvement. The science of sport was not even of interest to the fans who flooded the stadium at ancient Olympia to admire the winners, the great Olympians from different city-states, and to enjoy the exciting competition. No one cared.

A comparison with today’s necessary and compulsory recording of performance – a demand that comes mainly from the sponsors and the dictates of the Games’ massive commercialization – highlights the greatness of the men who created the Games back in those days.

“Our ancestors believed that putting emphasis on the performance of an athlete was not in tune with the ideals of athleticism and, therefore, they never kept such a record, even though there was a system for assessing the athletes.”

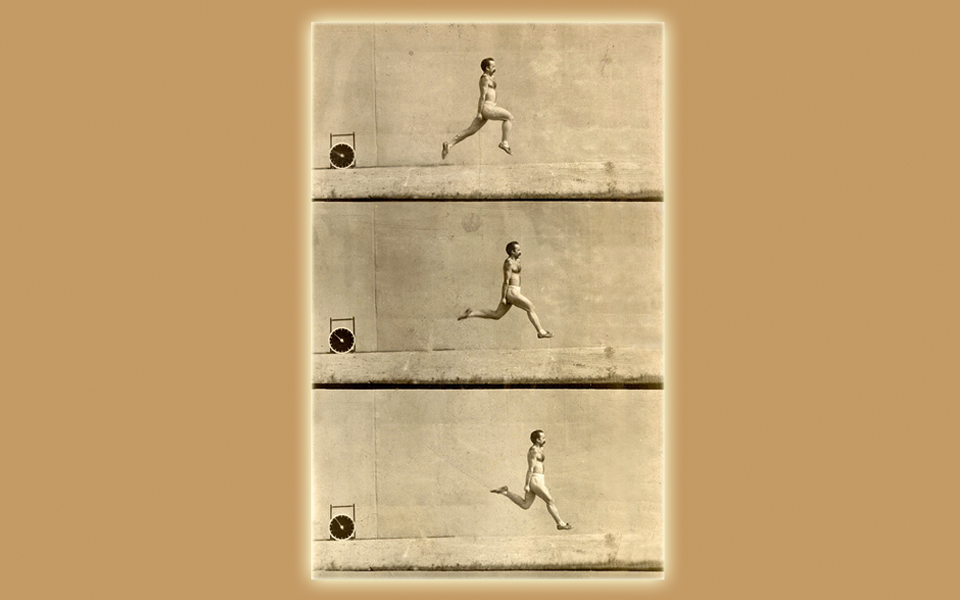

The answer to the first question, which holds true so far, is 776 BC, though it is almost certain that the Olympics had begun much earlier. In terms of history and sport, the first event was a race along the road of a stadium that was 192.27m in length. It is said, in fact, that the distance equaled the length of the foot of the demi-god Heracles, multiplied by 600. Interest, however, lay exclusively in who would cross the finish line first, rather than in how much time they did it. The same was later the case with the long jump, for example, where who won was more important than the distance they covered.

Our ancestors believed that putting emphasis on the performance of an athlete was not in tune with the ideals of athleticism and, therefore, they never kept such a record, even though there was a system for assessing the athletes. What the judges were looking for was an honest, courageous and persistent effort at improvement, with the ultimate goal being only to outdo oneself.

The term “record” did not exist in their vocabulary and this indifference may be directly associated with the changes observed in the regulations or even in the supervisory bodies from competition to competition. In contrast, as everyone in the world knows, the ancient Greeks loved their legends. So it was that our ancestors often tried to present reality with descriptive myths that usually diverged significantly from the truth. They said, for example that an athlete named Polymus Nestor – and this information has been recorded – could run fast enough to catch a hare, thus proving his speed.

Nowadays – starting with the modern Olympics of 1896 – performance records, and subsequently statistics, have become an inextricable part of athleticism and of the institution of the Games. Athletes and nations are judged almost exclusively by the numbers. When, for example, Jamaica’s Usain Bolt – the fastest man ever to have run – crosses the 100m finish line first, our eyes automatically turn to the numbers on the electronic scoreboard, looking for just one thing: has a world record just been broken, before our very eyes? Have we at least just witnessed the second-best performance of all times?

Victory alone is not as important today, particularly when it is achieved by the event’s favorite, as has been the case throughout Bolt’s reign from 2008 to the present.

Indeed, on consideration, there is something incredibly sad about how a victory, a personal achievement, becomes so downplayed when it is judged against the numbers produced by an electronic timer. In short, a Bolt victory alone impresses no one unless it comes with an impressive number after it – as though the fastest runner didn’t really break the ribbon first.