When my father was a small boy in Galveston, Texas, with no siblings to play with or anything like a helicopter parent regimenting his time, he roamed the inscrutable world of adults all around him. On one such sortie, rummaging behind his neighbor’s property, he found a neglected box of books, the names of which he recalls to this day with awe and precision. The first and most important was Will Durant’s 1926 classic, “The Story of Philosophy.” In its pages, he was immediately drawn to an image of Socrates, whose features reminded him of his grandmother’s pig. Far from repulsed, he lingered on the image, longing to comprehend why this funny-looking man who never wrote a word was revered throughout the ages.

Galveston is a port town, and even amid the segregation of the 1940s, the color line fluctuated. There was more cultural and class exchange than contemporary narratives of racial deprivation tend to allow for. My father’s family was not educated, yet the neighbor in question was the principal of the local Black elementary school. The house previously belonged to European immigrants. Ownership of the books was unclear. What my father knew was that he needed whatever was inside them, and so he asked to keep them. His neighbor’s generosity that day sparked a passion for reading and inquiry that would shape his entire life and alter its trajectory.

This story swelled long ago to the dimensions of a foundational myth. My father is our family’s First Man, a figure who created himself from scratch, initiating patterns of behavior and taste that did not exist before him but will outlast him now. If this were fiction, the symbolism would be heavy-handed: the fatherless Black boy stumbles upon Wisdom itself, is transformed by the Socratic injunction to know thyself and, through sheer imagination and willpower, weaves together an intellectual and ethical lifeline stretching back to Attica. Yet this story is essentially true, and it reverberated throughout my own childhood, guiding my course of study in college and throughout my adulthood.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

© Dimitris Tsoumpekas

That story was very much on my mind as our delayed Air France flight landed in Athens in July, for the first vacation out of the country that my wife, Valentine, and our two children, Marlow and Saul, seven and three, had taken together since the novel coronavirus upended the seasonal habits I’d grown so fond of after moving to Paris a decade earlier. Summer, in my mind, was synonymous with Italy. My best friend, Josh, who is my daughter’s godfather and had decamped to Moscow from Brooklyn, made an annual tradition of flying west to meet us.

For nine straight years, we found each other in Ischia or Florence or Puglia. Valentine preferred the stripped-down purity of the Greek islands but was always outvoted. It had taken COVID-19 to alter the calculus. Because returning from travel to Europe would be problematic for an American residing in Russia like Josh, Valentine found a whitewashed house above an undeveloped stretch of shoreline on the island of Tinos. We could spend part of the month there and another week in Athens. It was true that those colorful Italian bagni packed tight with sun loungers and umbrellas that I’d always found so convivial had lost some appeal in the age of social distancing, while the Cycladic beaches offered seclusion. And here was my chance to see the Acropolis. We booked the trip and then, in the days before we left, Josh learned that Russia’s travel restrictions had been eased. He was feeling a lot less picky now, and would join us on Tinos a few days later.

That afternoon, at the sole restaurant below our rental on Tinos, over cold white wine and what I came to understand is the platonic ideal of the traditional Greek salad, Valentine and I gazed across the turquoise sea at the daytime moon and the sun-baked silhouette of Ermoupoli in the distance. The logic of new traditions was suddenly persuasive.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

MY ACADEMY

I had flown with a hefty blue plastic binder labeled WILLIAMS ACADEMIC SERVICES. It was stuffed with hundreds of pages of test-prep materials bearing the same logo, which my father had lovingly and painstakingly assembled for my daughter, and I intended to use them. When I was growing up, he ran a business out of our home that, for ease of understanding, I would describe to strangers and acquaintances as a “test-prep service,” but anyone who knew us better understood that it was an “academy” in the classical, informal connotation of that word. No degrees or certificates of mastery were issued, but students – hundreds that I witnessed over the years – would pay a fee and come and sit with my father in the living room or kitchen, and he would, quite simply, improve their ability to reflect and reason. Most of the people who did this were teenagers trying to lift their GPAs or their SAT or Advanced Placement scores, but I have seen children as young as five and adults well into their 50s at his desk with pencil and paper. Plenty who couldn’t afford to pay received instruction pro bono.

Anyone under the impression that he or she was merely cramming for a standardized exam was in for an awakening when my father offered a modern poem or a passage of Confucius or Plutarch’s “Lives” to mull over. These were conversation starters. The students would soon be caught up in the thrust and parry of dialectic. Many came back year after year, long after they had achieved any specific objectives. My brother and I lived within the walls of that academy. As far as I am concerned, those three words making up the logo spell out the most powerful mnemonic device in the English language.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

Marlow was now the same age as I had been when my father first sat me down to say that I’d need to follow a program of study during the summers. And with the same technique he used to silence my childish tears, I had resolved to bribe her until she could see the intrinsic value. She is far more indomitable than I ever was, but through an improvisational combination of carrot (fresh smoothies) and stick (less screen time), I was able on some afternoons to turn the table on our terrace into an Aegean replica of the setup I’d spent so many hours contemplating in my New Jersey bedroom. When it was too hot to be at the beach, too hot to think about moving a muscle, we read Aesop’s fables and worked through sets of spatial-reasoning exercises, which, to my relief, she found the opposite of a chore, something akin to play, much the way I had. I have seldom been physically farther away and yet closer to my father in spirit than in these moments of improvised pedagogy. With the sudden distress the math problems sparked in her, it was as if the generations were collapsing — I was simultaneously both of them.

These sessions planted in me overly ambitious plans of turning the Greek capital into an open-air classroom. We arrived in Athens after dark on a Friday, checked into a centrally located hotel with a pool and free breakfast buffet, and took the elevator up to the roof deck for dinner. The moussaka was forgettable, but the panoramic views onto the city froze me in my chair. The Parthenon glowed at eye level, a pile of orange ember in the sky. I lost track of time contemplating its significance, as I would frequently come to do over the course of the week.

We’d been warned about the extreme heat of the mainland, but it surpassed all expectations, making it hard to maintain the teaching discipline I established on the island. With temperatures topping 100◦ F and not a single cloud to block the sun, Valentine found a solution in the form of a trilingual wunderkind of a 14-year-old named Margot. The daughter of a friend of a friend, she gamely stayed in the air-conditioned room or at the pool with the kids.

I had wanted to impress upon my daughter the feminist aspect of Athens, a city brought to life by the mythological victory of Athena, goddess of wisdom and strategic warfare, over Poseidon, ruler of the sea. She was much more interested in the flesh-and-blood example of Margot, who quickly won the admiration of the adults as well when she helped finagle us a table at the packed neighborhood taverna near her family’s apartment. Stepping out of the taxi, she produced a notebook and delivered all our orders directly to the kitchen before retiring for the evening. Heaping plates of stewed rabbit, lamb, fish, potatoes, salad and meatballs and delicious, nondescript wine served in metal containers appeared before we fully grasped what had even happened.

Over the course of our stay, a relentless sun beat down on the nearly deserted ancient Athenian Agora, a small, parched and rocky patch of land that provoked in me the same telltale shiver down the spine that I’ve only ever felt in the garden of Gethsemane and parts of the Vatican. An overwhelming proportion of the world we take for granted today was birthed in these cramped spaces. Josh and I sat among the pillars and rubble, and I labored to envision Socrates darting through the hurried masses, pestering everyone with questions so insightful and inconvenient that he would eventually have to be killed for their perspicacity. When I looked up, it hit me that he was tried and convicted on the hill directly above us.

On our second-to-last day in Athens, we met Margot’s mother, Irène, and Valentine’s friend Sebastien in Exarchia, the traditionally anarchist neighborhood at the center of the 2008 riots that broke out in response to the police killing of a 15-year-old. Sebastien had recently moved from Paris to simplify his life and to work at Irène’s fashion label, Kimalé. After lunch, we visited the small, treasure-packed atelier where they produce clothing and handmade jewelry for women. While Valentine shopped, I realized there was someplace I needed to take Marlow. I ordered an Uber and 15 minutes later the two of us were standing in the blazing heat of a not particularly well maintained public park in the nondescript Akadimia Platonos quarter, next to modest apartment blocks, auto-repair shops and Orthodox churches. With the aid of some precise geotags I had found on a particularly helpful blog, we located the unobtrusive signpost giving context and directions to the rectangles of stones protruding from the dirt in several expanses. “What are we doing?” Marlow asked, and I explained again that we were looking for the footprint of a structure that, in some imagined but also not at all insignificant way, had reached across millenniums to grab her grandfather and nudge him beyond his circumstances.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

PLATO ‘S ACADEMY

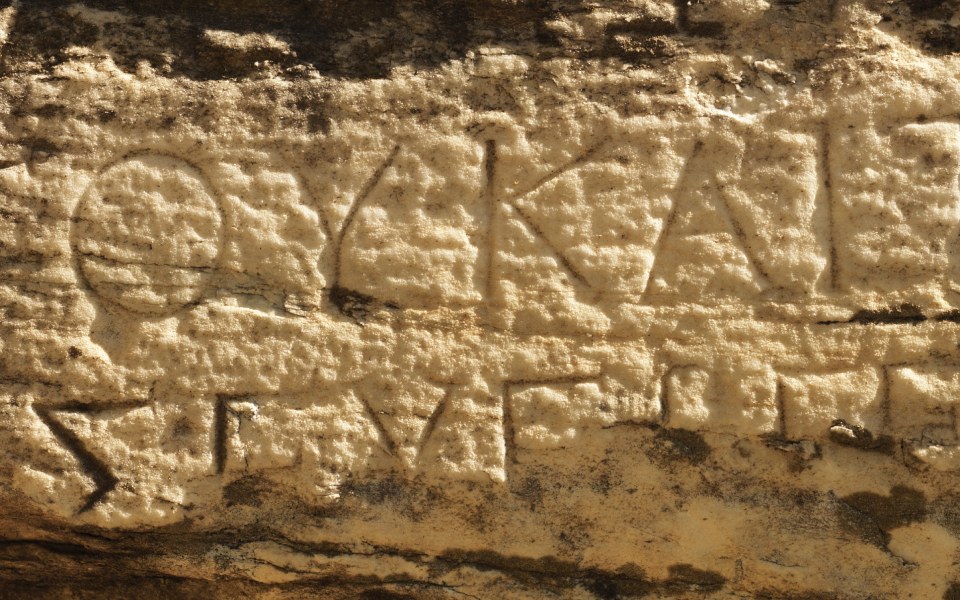

I repeated to her the anecdote about how my father discovered the image of Socrates, which led to a lifelong devotion to his student Plato, in whose dialogues his genius is preserved. Somewhere in this park were the archaeological ruins of Plato’s Academy, where he taught, among others, Aristotle, tutor of Alexander the Great and one of the finest minds the world has ever witnessed. These men actually studied here, I told her. The academy endured from 387 BC until the death of its last head, Philo of Larissa, just over 300 years later. The ruins had been lost to history until the 20th century. In another era, we would have missed it.

We stood now in the original Grove of Academe, and I asked Marlow if she recognized the word from the top of all the papers her grandfather had given us. According to classical mythology, this plot of land was sacred; it had been a haven to Athena since the Bronze Age and was subsequently named after its legendary owner, the hero Akademos, who’d revealed to the Spartans where King Theseus had hidden Helen (not yet of Troy) and spared Athens bloodshed. It was for this reason that Plato called his school, set on Akademos’ land, an “ακαδημία,” and it’s because of that choice that centuries later the French “académie” would filter into English and eventually inform those toner-stained sheets of paper we both pored over.

This was where we know that Plato developed and lectured on the Good — or value itself, something even “greater than justice and the other virtues” — which he made famous in “The Republic” through Socrates’ ventriloquy. Some things are better than others, and it is necessary to distinguish. In his own framework, what we have been left with is a vastly inferior form of philosophical transmission. For Plato and Socrates, speech was inherently superior to writing because writing was no longer living. The pupils who had the chance to sit before Plato in this garden were some of the luckiest in all of intellectual history. They practiced their discipline as it was meant to be practiced and, it occurred to me then, as my father practiced it with me, and as I was now trying my best to capture in my sessions with my daughter.

As I talked, Marlow nodded at me the way I used to nod at him. She would encounter all this history later; we would revisit it. Now I simply wanted her to understand what stores of hope and motivation he had drawn from this place that, I reflected, he’d never set foot in but had nonetheless taught himself to yearn for. It may just be a testament to the very success of his endeavor that she cannot — not fully — intuit the force and improbability of his self-invention. What she could tell was that I do, and she hugged me tightly as we fell into a happy silence.

I took her hand as we followed the instructions across the field for several hundred feet, not a single soul around us. Then, in a clearing of trees, the ground dipped slightly, and we were upon it. Large rectangular stones formed the outlines of rooms, the very rooms whose walls once reverberated with the voices of the philosophers. I told my daughter then that I don’t believe it is an exaggeration to say that – in some small but very real way – these rooms made possible our own fleeting existence.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times Magazine.