Beyond Delphi: Exploring the Lesser-Known Centers of Ancient...

Discover the lesser-known oracles of ancient...

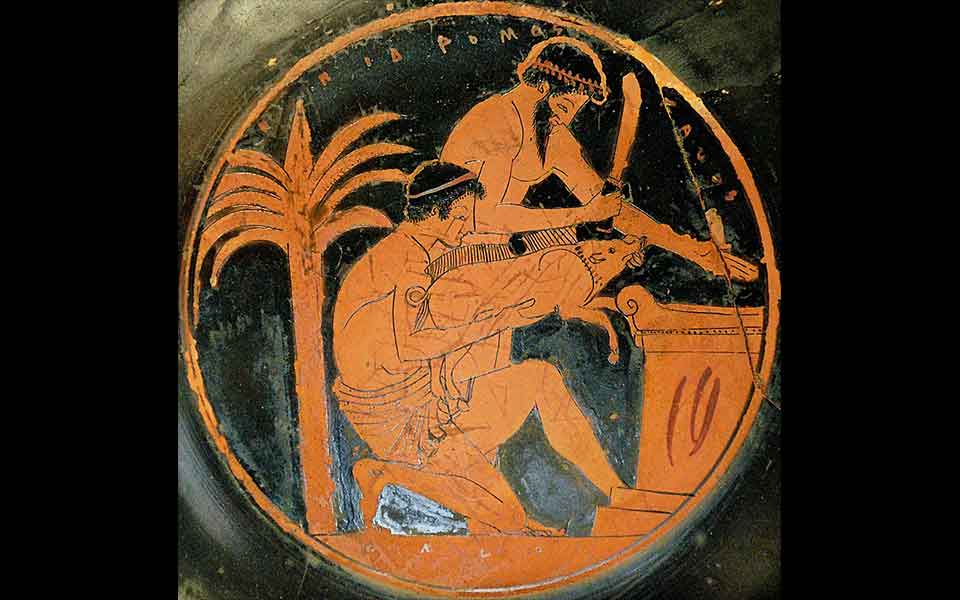

Meat was often roasted or boiled for public consumption after a blood sacrifice to the gods. Here, two men prepare to sacrifice a pig (Attic red-figure cup, 510–500 BC, by the Epidromos Painter).

As the aroma of sizzling meat fills the air on Tsiknopempti, or “Smoky Thursday,” Greeks everywhere prepare for a feast steeped in history. This annual celebration, held during the Greek Carnival season, is a time to indulge before the fasting of Lent begins. But the tradition of coming together over grilled meats goes back much further than modern street barbecues and the local “souvlatzidiko” (purveyors of the beloved meat on a skewer, souvlaki) – it reaches deep into the religious, social, and even athletic life of ancient Greece.

So, how did the Greeks of antiquity consume meat? Was it an everyday staple or a sacred luxury? And what would a Homeric hero, an Olympian wrestler, or a Pythagorean philosopher think of our modern-day feasting? Let’s take a journey through the rituals, banquets, and even fast-food culture of the ancient Greek world.

A modern echo of ancient traditions: the smell of grilled meat fills the night air on “Tsiknopempti” (“smoky Thursday”).

© Shutterstock

In ancient Greece, meat was more than just food – it was a divine gift, a conduit between mortals and the gods. One of the most common ways for a Greek, especially the poor, to eat meat was through religious sacrifice, known as “thysia.”

A typical sacrifice involved slaughtering an animal – often a cow, pig, sheep, or goat – and offering the gods their share. The process was meticulous: the animal was consecrated by a priest, its throat slit, and select bones, such as thigh bones and tail vertebrae, were wrapped in fat and burned on the altar, sending up fragrant smoke (“knise”) to the heavens.

The epic poet Homer (8th century BC) describes these rituals in vivid detail. In Book I of the “Iliad” (458–472), the Achaeans honor Apollo with a sacrifice, burning the thigh-bones while a priest pours a libation of “gleaming wine over them.” After “tasting the entrails,” the remaining meat is “cut into pieces and pierced with spits” and roasted and distributed among the men – an early version of souvlaki or “kontosouvli” (spit-roasted pork) as we know it today!

Another passage, this time in Book III of the “Odyssey” (5–10), describes the visit of Telemachus, Odysseus’ son, to king Nestor at Pylos. He arrives amid a grand sacrificial feast in honor of the sea god, Poseidon. On the shore, the Pylians sacrifice 81 “black bulls to the dark-haired Earth-shaker,” roasting the meat before partaking in a communal feast.

These sacrificial feasts were more than just meals – they reinforced social bonds and hierarchies. Prime cuts were reserved for elites or priests, while the rest was divided among the other participants. The historian Herodotus (c. 484–c. 425 BC) recounts that in Sparta, meat from sacrifices was allocated based on civic rank, ensuring that food distribution reflected societal structure:

“At all public sacrifices the kings first sit down to the banquet and are served first.” (Histories 6.57 ff)

According to archaeologist and historian Gunnel Ekroth, meat in large-scale sacrificial feasts was often boiled in a cauldron, making it more tender and easier to distribute. This process also eliminated distinctions between different cuts of meat, which often included entrails, inner organs (offal), and occasionally even meat from dogs, horses, and donkeys …!

But what about meat that wasn’t part of a sacrifice?

Cooking rabbit stew in a clay cookware pot over a wood fire in rural Crete.

© Shutterstock

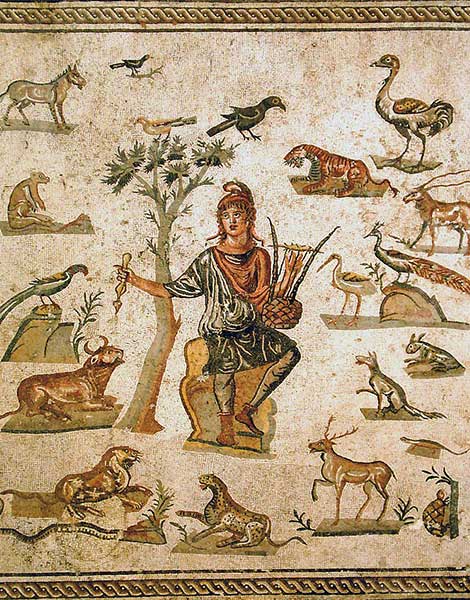

Although religious sacrifice was the most culturally significant way to eat meat in ancient Greece, it wasn’t the only one. Osteological evidence from archaeological sites suggests that hunting and trapping provided another source of meat, particularly in rural settlements. Wild game such as deer, boar, rabbit, hare, and a variety of birds – including pheasants, partridges, quails, thrushes, blackbirds, and ducks – regularly appeared on Greek tables, alongside farmyard animals like chicken and geese.

Writing in the 4th century BC, Xenophon describes how wild boars, deer, and “all manner of beasts of the chase” were hunted at Artemis’ sanctuary in Skillous (Scillus), near Olympia in the northwest Peloponnese. These animals were later roasted and enjoyed during festivals (Anabasis 5.3.8 ff.).

Beyond hunting, butchers in the agora (marketplace) played a key role in meat consumption. The philosopher and naturalist Theophrastus (c. 371–c. 287 BC), in “Characters” (9.4), humorously remarks that if one cannot get a proper cut of meat from a butcher, they should at least get “something for the broth.” While a commercial meat trade existed in towns and cities, allowing some Greeks to purchase meat outside religious contexts, it remained an expensive commodity for most. Aristophanes, the 5th-century BC comic playwright, notes in “Peace” (line 374) that a young pig cost three drachmae, equivalent to three days’ wages for a public servant.

While meat-eating in the Homeric epics is often linked to ritual sacrifice, there are instances where characters eat meat without first offering it to the gods. Perhaps the most striking example is the notorious suitors of Penelope, Odysseus’ long-suffering wife, who constantly gorge on the absent king’s livestock in Ithaca without offering the gods their share in true piety (Odyssey 1.106 ff., 17.332 ff.). Their gluttonous and disrespectful behavior reinforces the idea that large-scale feasting should be accompanied by the proper rituals.

Athletes wearing "perizoma" (loincloths) while training. Attic black figure kantharos, c. 520-500 BC.

Meat wasn’t just for religious or communal feasts – it also played a crucial role in athletic training and military life.

According to some sources, early Greek athletes followed mostly vegetarian diets, relying on figs, cheese, and barley. But by the 6th century BC, meat had become a key component of an Olympian’s nutrition plan. Wrestlers and boxers, in particular, consumed large quantities of meat and bread to build muscle, a practice known as “forced nutrition.”

Perhaps no one embodied this meat-heavy diet more than Milo of Croton (fl. 540–511 BC), a legendary six-time Olympic champion from Magna Graecia. Ancient sources claim he ate 20 pounds of meat per day, washed down with copious amounts of wine. Writing in the 1st century BC, Diodorus Siculus describes how Milo wore a lion’s skin and carried a club, mimicking the divine-hero Heracles.

The Spartans, famed for their warrior society, also valued meat as a source of strength. Their diet included the infamous “black soup,” a dish made from pigs’ legs and blood. Another staple, made with pork, salt, vinegar, and blood, was often served with “maza” (barley flour dumplings), along with figs and cheese – a meal designed to sustain hardened warriors in battle and training.

However, not everyone approved of such meat-heavy diets. Writing centuries later, the Greek physician and philosopher Galen (129–c. 216 AD) criticized excessive meat consumption, believing it could be detrimental to health.

Despite the debate, the connection between meat, strength, and endurance was firmly established, shaping Greek views on nutrition, athleticism, and warfare for generations.

Orpheus surrounded by animals. Ancient Roman floor mosaic, from Palermo, now in the Museo archeologico regionale di Palermo

© Giovanni Dall'Orto / Public domain

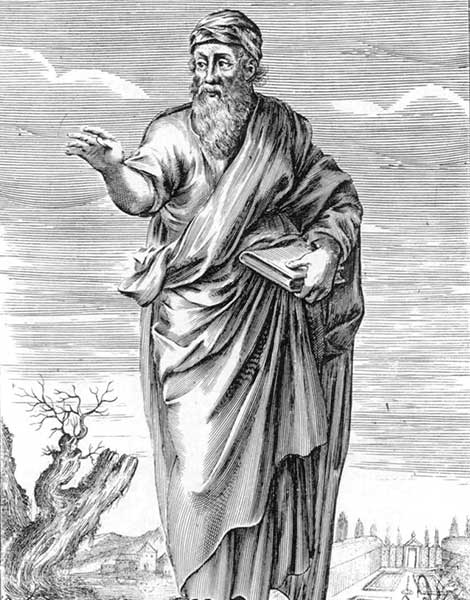

Greek mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras (c. 570-495 BC) voiced his moral objection to the mistreatment of animals.

Of course, not all Greeks embraced meat consumption. Certain religious and philosophical movements actively promoted vegetarianism, viewing it as a purer way of life, rooted in nature.

The Orphics and Pythagoreans, for example, saw meat-eating as spiritually corrupt. Pythagoras, the 6th-century BC philosopher, famously condemned eating animals, equating it with cannibalism:

“Oh, ponder a moment such a monstrous crime – vitals in vitals gorged, one greedy body fattening with plunder of another’s flesh, a living being fed on another’s life!” (Ovid, Metamorphoses 15.60 ff)

He and his followers instead promoted a diet of fruits, grains, and legumes, believing that all living beings possessed souls. Though not widespread, such ideas planted the seeds of ethical vegetarianism, which would re-emerge in later historical periods.

Meat or no meat, the average Greek diet was frugal, revolving around the “Mediterranean triad” of cereals, olives, and grapes. By the 5th century BC, references to meat consumption become less prominent in the ancient texts, leading many scholars to believe that it was a rarity, certainly when compared to today’s standards.

For more on the topic of meat abstinence in ancient Greece, click here.

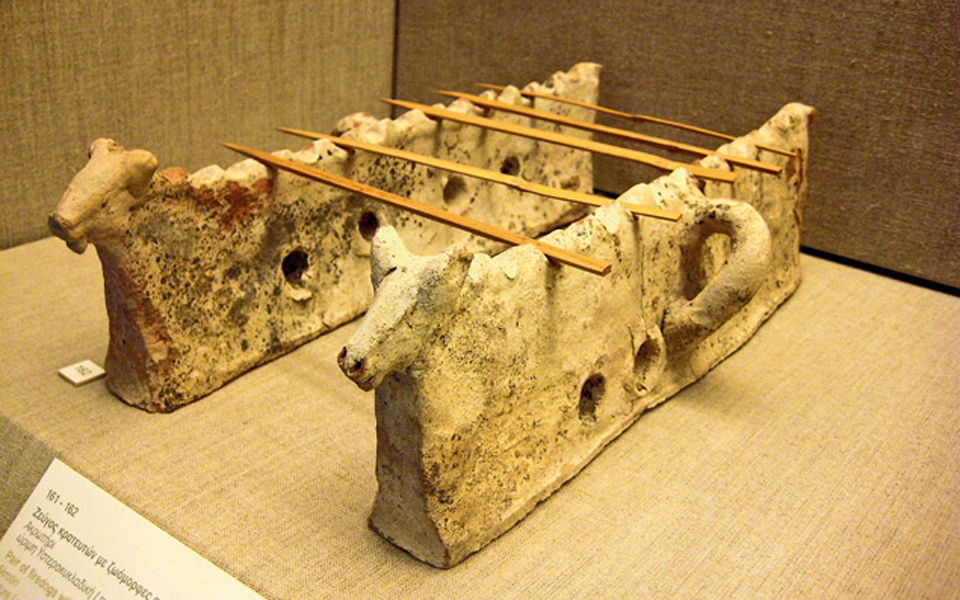

Prehistoric souvlaki tray: a pair of clay supports (firedogs) used to grill meat on skewers, shaped with bulls-head finials (c. 17th century BC). On display at the Archaeological Museum of Thera.

If you think fast food is a modern invention, think again – the ancient Greeks also enjoyed quick, handheld meat snacks.

While meat was generally expensive in the city marketplaces, pork and sausages were more affordable exceptions, making them popular among both rich and poor. Sausages, in particular, were widely consumed, and sausage vendors were a common sight in the agora. In “The Knights” (424 BC), Aristophanes mocks these rowdy, shrewd merchants, portraying them as crafty businessmen vying for customers in the bustling marketplace.

The tradition of grilled meat skewers dates back even further. At the Bronze Age settlement of Akrotiri on Santorini, archaeologists discovered grilling racks and a firebox with a flat griddle, providing evidence of souvlaki-style skewers and pita dating back some 3,700 years.

In the bustling agoras of Greek cities, street vendors sold quick meals to busy citizens, particularly those who lacked their own kitchens. Though the fixed food stalls known as “thermopolia” (literally “a place where something hot is sold”), were a later Roman development, Greek marketplaces were home to independent food sellers offering grilled meats, bread, and other prepared dishes. Among the most popular street foods were grilled pork skewers (“obeliskoi,” an early form of souvlaki), wrapped in bread and often served with a dollop of mustard – a popular Greek condiment mentioned by Theophrastus (“Enquiry into Plants”).

Other condiments enhanced flavors: mustard mixed with olive oil and vinegar added a bold kick to meats, while a garlic-and-yogurt sauce, similar to tzatziki but without cucumber, was also common. Meanwhile, fish-based sauces and honey glazes provided either a savory depth or a touch of sweetness to grilled dishes.

These street food vendors were more than just a place to grab a quick bite – they created lively social hubs where citizens, merchants, and travelers gathered to eat, gossip, and debate. The agora, filled with the aromas of roasting pork and lamb, became a culinary hotspot, proving that the love for fast, affordable, and flavorful street food has deep roots in Greek history.

For more on the earliest evidence for Greece’s most beloved street food, click here.

Fast forward to today, and Tsiknopempti continues Greece’s long love affair with grilled meats.

Eleven days before Clean Monday, which marks the start of Lent, Greeks gather to feast on meat before the fasting period begins. Streets, tavernas, and homes fill with the smoky aromas of souvlaki, sausages, and steaks. In fact, the name “Tsiknopempti” comes from “tsikna,” meaning the savory smell of roasting meat, and “Pempti,” meaning Thursday.

In some regions, Tsiknopempti has its own unique customs. In Serres, for instance, men leap over barbecue flames once the meat is cooked – a practice believed to bring good luck. On the island of Corfu, locals gather in town squares for lively gossip sessions, playfully parodying public figures in a tradition of lighthearted satire.

Despite the millennia of change, one thing remains the same: meat feasting is a time for community, celebration, and tradition.

So, as you take a bite of juicy souvlaki this Tsiknopempti, remember – you’re not just enjoying a meal. You’re partaking in a tradition that stretches back to Homeric feasts, Olympic champions, and the smoky altars of the gods themselves.

Discover the lesser-known oracles of ancient...

Before passports and package tours, pilgrims...

Antiques expert and collector Dimitris Xanthoulis...

Souvlaki joints started appearing in earnest...