In the pre-dawn hours, a lone monk moves silently through the shadowed corridors of a monastery on Mount Athos (Aghion Oros, or the “Holy Mountain”), the self-governing monastic republic in northeastern Greece. The scent of burning incense lingers in the cool air. He steps into a candle-lit chapel, where the flickering light casts shifting patterns over centuries-old frescoes blackened by time and devotion. Bowing deeply, he whispers the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” This simple yet profound invocation, endlessly repeated, lies at the heart of Orthodox monastic life – a tradition that has endured, largely unchanged, for over a thousand years.

Though Greece is celebrated for its ancient ruins, sun-drenched islands, and bustling cities, a very different world exists within its monastic enclaves. In places like Mount Athos and Meteora, monks withdraw from the distractions of modern life to embrace a rhythm of prayer, manual labor, and contemplation. But where did this tradition originate? And how did these monastic communities shape Greece’s spiritual landscape, transforming remote mountains and cliffs into sacred havens of devotion?

© Shutterstock

The Birth of Monasticism in Greece

Christian monasticism (from the Greek word “monachos,” meaning “solitary”) first emerged in the deserts of Egypt during the 3rd and 4th centuries. Pioneering ascetics like St. Anthony the Great (251–356 AD) and St. Pachomius (c. 292–348 AD) withdrew from urban life to seek God in solitude, fasting, and unceasing prayer. Their radical devotion inspired a growing movement that spread across the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, taking root in Syria, Asia Minor, and eventually Greece.

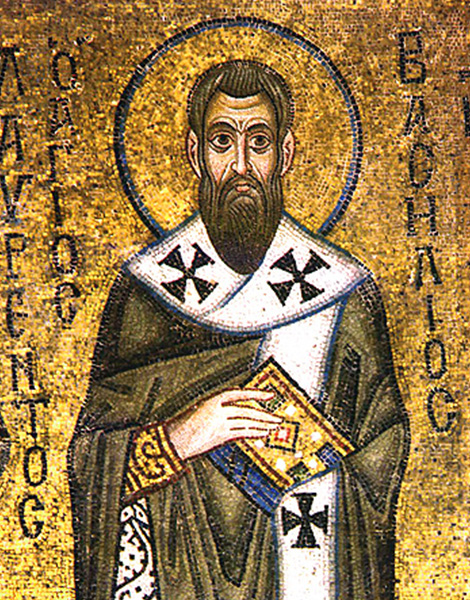

By the 4th century, Greek-speaking monks had begun establishing their own hermitages, often in remote caves or perched on rocky outcrops. Some embraced complete isolation, while others formed small communities, laying the foundation for organized monastic settlements. The most influential early figure in Greek monasticism was Basil of Caesarea (c. 330–379), also called St. Basil the Great, whose ethical manuals (the “Moralia” and “Asketika”) provided a framework that would shape Orthodox monastic life for centuries. Basil emphasized a balance between solitude and communal living, encouraging monks to dedicate themselves to prayer, manual labor, and acts of charity.

In Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey), monks carved entire churches and monastic dwellings into soft volcanic rock, creating natural fortresses that offered protection from persecution and invading forces. Similarly, in Greece, early Christian hermits sought refuge in the caves of Mount Olympus and the rugged landscapes of the Peloponnese. These isolated sanctuaries laid the groundwork for the great monastic centers that would flourish in the centuries to come.

One of the most extreme expressions of Christian asceticism was the “Stylite” movement. Stylites (from the Greek “stylos,” meaning “pillar”) were monks who lived atop tall stone columns, exposed to the elements, in a radical act of devotion. These towering ascetics were revered as living saints, drawing pilgrims who sought their blessings, confessions, or miraculous healings.

Among the most renowned Greek Stylites was St. Daniel the Stylite (c. 409–493), whose fame spread beyond the Byzantine world. Inspired by St. Simeon Stylites of Syria (c. 390–459), Daniel spent 33 years atop a column near Constantinople, offering spiritual guidance to emperors and commoners alike. His influence cemented the Stylite tradition as a revered form of asceticism, with similar practices emerging in parts of Greece.

© Shutterstock

Mount Athos: A Monastic Republic

By the 10th century, monasticism in Greece had evolved from scattered hermitages into large, organized communities. Nowhere was this transformation more profound than on Mount Athos, the easternmost of the three peninsulas of Halkidiki in northern Greece that became a sanctuary for monks seeking refuge from war and political upheaval.

With the support of Byzantine emperors like John I Tzimiskes (r. 969–976), Mount Athos was granted autonomy as a self-governing monastic republic. Over time, it became home to twenty grand monasteries, each preserving Orthodox traditions, priceless manuscripts, and sacred art. Unlike the rest of Greece, Mount Athos remained largely untouched during the four centuries of Ottoman rule (“Tourkokratia”), maintaining its independence as a spiritual stronghold.

Mount Athos also became the center of “Hesychasm,” a mystical tradition emphasizing inner stillness and divine illumination. Hesychast monks sought spiritual union with God through the continuous repetition of the Jesus Prayer, often in deep meditation.

© Shutterstock

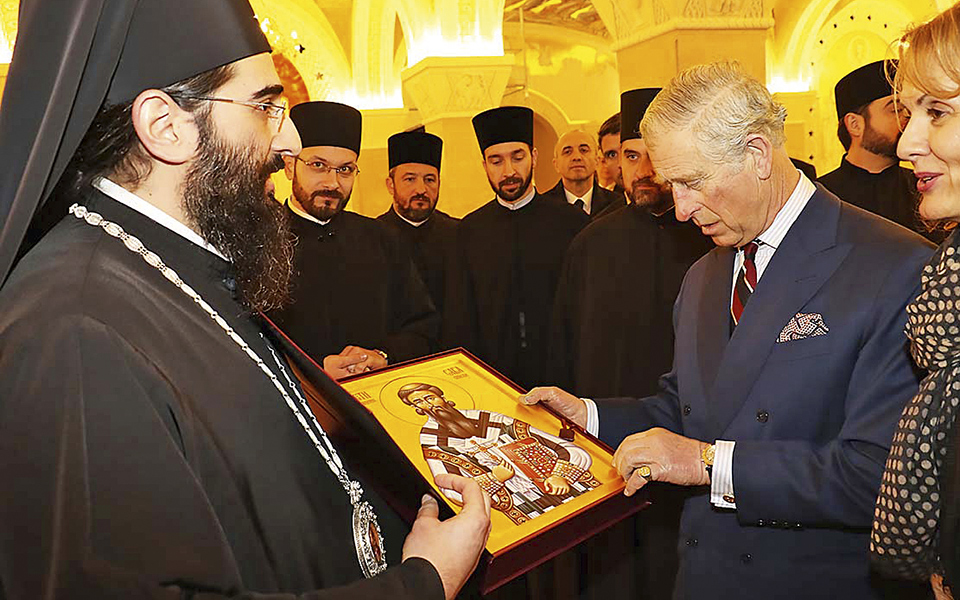

Even today, Mount Athos remains a living relic of medieval monasticism. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the mountain is home to around 1,400 monks, spread across its twenty monasteries (17 Greek, one Russian, one Serbian and one Bulgarian), as well as smaller “sketae” (daughter houses of the monasteries), “kellia” and “kathismata” (cells for one solitary monk). Ancient customs persist, from rigorous fasting and prayer schedules to the strict prohibition of women – a rule upheld for over 1,000 years.

According to tradition, the Virgin Mary (Panaghia) and the Apostle John visited Mount Athos while traveling to Cyprus, to visit the resurrected Lazarus. Their ship was caught in violent storm and blown off course. As they neared the peninsula, a divine voice proclaimed that the land was to be her personal garden. From that moment on, Mount Athos was dedicated to the Theotokos (Mother of God) – the “Garden of the Panaghia” – and no other women were permitted to set foot on its soil. The prohibition, known as the “Avaton,” is upheld to maintain the monks’ spiritual focus and to preserve the mountain as an earthly extension of Mary’s purity. Even female animals, apart from birds and insects, are generally not allowed on the peninsula.

Monks here see themselves as the spiritual successors of the desert fathers, preserving the Orthodox faith through prayer and study. Even in today’s digital age, most Athonite monks avoid modern technology, shunning phones, computers, and even electricity. However, some monasteries have cautiously adopted solar panels to provide essential lighting and heating during the harsh winter months.

Male visitors can apply for a special permit (“diamonitirio”) to enter Mount Athos, but only a limited number are allowed per day. Those who make the pilgrimage experience a monastic world almost untouched by modernity. For more information, visit the official website: mountathosinfos.gr

© Shutterstock

Meteora: Monasteries in the Sky

Rising dramatically above the plains of Thessaly, Meteora is one of Greece’s most awe-inspiring landscapes and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Towering rock pillars, shaped by wind and water over millions of years, provide a seemingly impossible foundation for ancient monasteries that appear to float between earth and sky. These secluded sanctuaries were originally accessible only by rope ladders and pulley systems, ensuring the monks’ isolation from worldly distractions – and from invading forces.

The first hermits arrived in Meteora during the 11th century, drawn to its sheer cliffs and natural caves as places of solitude and prayer. Over time, scattered hermitages evolved into organized monastic communities. By the 14th and 15th centuries, at the height of Meteora’s monastic era, 24 monasteries stood perched atop the rock formations. Today, only six remain active, carefully preserved as living centers of Orthodox spirituality.

© Shutterstock

The Holy Monastery of Great Meteoron is the largest and most historically significant. It was founded in the mid-14th century by St. Athanasios the Meteorite, a scholarly monk from Mount Athos. His successor, Saint Joasaph, was a Serbian king of Byzantine descent who renounced his throne to embrace monastic life at Meteora at the age of 22. These monasteries became strongholds of Orthodox faith, safeguarding religious traditions and manuscripts through centuries of political turmoil.

Unlike Mount Athos, Meteora welcomes both men and women. Visitors can explore the monasteries, admire centuries-old frescoes, and experience the quiet devotion still preserved within these sacred walls. Though Meteora has become one of mainland Greece’s most popular tourist destinations, attracting thousands of visitors each year, its monastic communities of both monks and nuns remain committed to prayer and hospitality.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

The Unchanging Rhythm of Monastic Life

For Orthodox monks, time moves to a different rhythm – one shaped not by the modern world but by the ancient monastic “Typikon,” a liturgical book that has governed monastic life for centuries, and the three basic virtues: celibacy, obedience, and poverty. Their days revolve around three core pillars: liturgical prayer, manual labor, and inner stillness, known as “hesychia.” The monks devote themselves to long, solemn church services filled with haunting Byzantine chants, to the work of their hands – tending gardens, making wine, painting icons, and preserving manuscripts – and to silent prayer and meditation, centered on the ceaseless repetition of the Jesus Prayer.

At 3.30 am, while the outside world remains in deep slumber, the monks awaken for the Midnight Office (known as “Matins” in the Western rites) – the first prayers of the day. As they chant the Psalms in Byzantine Greek, their voices rise and fall in rhythmic prayer, connecting them to generations of monks who have stood in the same place before them.

After morning prayers, they gather for a silent meal at 7.30 am, known as the “Trapeza.” Food follows strict fasting rules – meat is never consumed, and dairy is often restricted. As they eat, one of their brethren reads aloud from the “Lives of the Saints,” ensuring that even mealtime is an opportunity for spiritual reflection.

For more on the food cooked by the monks on Mount Athos, click here.

Though many imagine monks as detached from the world, their daily labor – referred to as “common obedience” – is both practical and deeply spiritual. On Mount Athos, some monks devote their time to winemaking and beekeeping, producing Athonite wines and honey that are renowned worldwide. Others train as iconographers, following the Byzantine artistic tradition and painting religious icons through prayer. Some dedicate themselves to the careful restoration of ancient manuscripts, preserving Orthodox heritage one fragile page at a time. Others work as farmers and carpenters, growing olives, wheat, and vegetables or crafting wooden artifacts to support their monastic communities.

Even time itself moves differently here. Mount Athos still follows the old Julian calendar, making it 13 days behind the rest of the world. Within its monasteries, time is not marked by the ticking of a clock but by the rhythmic ringing of the “semantron” – a wooden or metal board struck with a mallet, calling the monks to prayer.

The Future of Orthodox Monasticism

The traditions established by Greek Orthodox monks – solitude, prayer, and ascetic devotion – continue to shape the spiritual landscape of Orthodox Christianity. Pilgrims journey to Mount Athos and Meteora, seeking wisdom and guidance from those who have preserved these ancient practices for centuries.

In recent years, monasticism has seen a quiet revival, as young men (and women), disillusioned by materialism and nihilism, turn to monastic life in search of deeper meaning. New monasteries, inspired by the Mount Athos tradition, have been founded in the US, Europe, and Australia, offering spiritual refuge in an increasingly restless and uncertain world. This renewed interest is not confined to Orthodoxy – Catholic monastic orders, such as the Benedictines and Carthusians, and even certain Protestant communities, continue to attract those drawn to contemplation, prayer, and simplicity.

As long as there are those who seek a deeper spiritual life, the monasteries of Mount Athos and Meteora will endure – silent islands of prayer in a world that never stops moving.