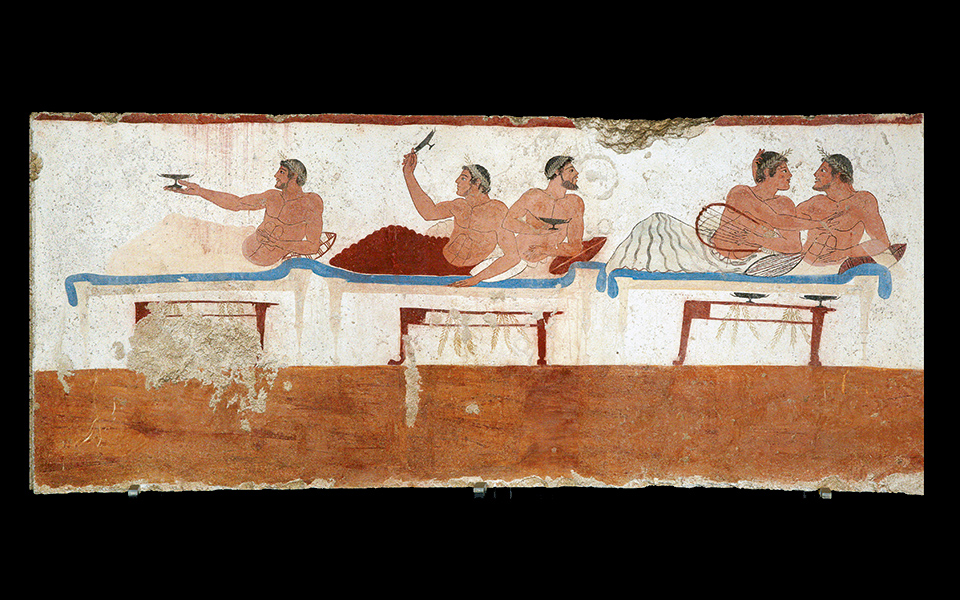

Wine and its consumption played a regular role in religion during Classical times (5th, 4th c BC), most ostensibly through the cult and festivals of Dionysus. In Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, the Athenian women confirm their agreed conspiracy, to abstain from sex until their menfolk have ended the Peloponnesian War, by swearing a solemn oath over a bowl of Thracian wine. In early comedic contests, the prize for the winning poet was a basket of figs and a jar of wine. Where wine was most lavishly dispensed, however, was at symposia. Peter Bing observes: “The symposium is not just one of the most central but arguably the best attested social institution of ancient Greece.” We learn of these drinking parties through poetic, historical and philosophical texts, painted scenes on ceramic drinking wares and the archaeological exploration of countless private and public rooms in which they were set.

Every Athenian of means had a room in his house specially designed and reserved for male parties. This “andron” (men’s room) was lined with couches, on which the host and his guests would recline on their left elbows, enjoying food, drink, games and conversation, as well as music, dancing and often sex provided by hired female entertainers (hetairai). A favorite game was kottabos, in which revelers flung at each other, and tried to catch, the dregs of their wine. Many vase painters, according to Bing, depict uninhibited communal sex as the climax to the symposium; the guests themselves are shown as lustful, wine-swilling satyrs, grossly-featured men with horses’ tails and ears – followers of Dionysus, who may best be remembered as prototypical “party-animals.”

The andron was also furnished with low tables and a sophisticated array of banqueting equipment, including a footed wine amphora (pelike), water jar (hydria), large, standing mixing jar (krater), smaller mixing vase (stamnos), wine-chiller (psykter), serving pitcher (oinochoe) and various types of drinking vessels (shallow, stemmed kylix; two-handled kantharos; large skyphos). The room’s centerpiece was the krater, adorned with garlands, symbolizing (with its wine) the god Dionysus himself.

The most popular wines consumed at symposia came from Chalkidike, Ismaros, Chios, Cos, Lesbos, Mende, Naxos, Peparethos (Skopelos) and Thasos. “Bibline” wine may have been a local imitation of Phoenician wine from Byblos, produced on Thasos. Theophrastus (ca 371 – ca 287 BC) describes various substances commonly added to wine, including perfume, honey, seawater, brine, oil, herbs, resin and spice. The symposium’s host was in charge of the mixing jar: he decided how much wine his guests would drink and how inebriated they would be allowed to get. Eubulus (ca late 370s BC) offers a humorous list of guidelines, spoken as Dionysus’ own words, cautioning how many kraters a moderate host should mix and what effects his guests might expect from overconsumption:

“The symposium’s host was in charge of the mixing jar: he decided how much wine his guests would drink and how inebriated they would be allowed to get.”

“As wine’s economic and social value increased in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, so did the interest taken in it by scholars, scientists, comedic authors and common wags.”

Three kraters only do I mix for the temperate – one to Health, which they empty first. The second to Love and Pleasure, the third to Sleep. When this is drunk up, wise guests go home in peace. The fourth krater is mine no longer, but belongs to Insolence; the fifth to Shouting; the sixth to Drunken Liberties; the seventh to Black Eyes. The eighth is the Court Summoner’s; the ninth belongs to Irritability; and the tenth to Madness, Arms and Death.

Although ancient symposia are often associated today with sophisticated philosophical discourse concerning beauty, wisdom or virtuous love, thanks to such literary works as Plato’s Symposium, or that of Xenophon, in reality they were frequently occasions for excessive drinking, leading to licentiousness, mayhem and violence. A later Symposium, penned by Lucian in the 2nd century AD, describes a banquet that descended into a bloody brawl – led by the Cynic philosopher Alcidamas – which left guests with broken bones, smashed teeth and other serious injuries. The stock ancient joke was that the worst-behaved guests at a symposium were the philosophers.

As the party ended or became boring, it was usual for guests to depart in groups, riotously roam the streets and enter other symposia uninvited. In many cases, symposia served as regular gatherings for disgruntled aristocrats, increasingly weak in the face of rising democratic power, who drank wine and commiserated together, afterwards taking to the streets to show their drunken defiance of a distasteful authority.

As wine’s economic and social value increased in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, so did the interest taken in it by scholars, scientists, comedic authors and common wags. Theophrastus, originally a student of Plato, produced a study of vineyard soils and which of these best served specific grape varieties. He also revealed that by reducing their yields, winemakers could achieve greater quality and stronger flavor in their products. Aristotle, ever the sober scientist, was keen to understand the effects of wine consumption, but may have been going too far when (in a now-lost treatise On Drunkenness, cited by Athenaeus) he offered formalized observations on how drinkers fall when under the influence of certain intoxicants: people drunk on barley wine fall only on their backs and lie face up; people affected by all other drinks fall in all directions – to the left, the right, on their faces or on their backs. Drunkenness was a favorite source of humor for writers of comedies in Classical Athens, who included in their plays such stock characters as the female Old Drunkard. By Roman times, another comedic figure had appeared that still rings true today: the blockhead, lackadaisical student, Scholastikos, who knows more about popular songs than his tutors’ teachings and squanders all his parents’ wealth on wine.