The ‘hole’ – that is how, for decades, passersby in the neighborhood of the Acropolis would refer to the cave that was visible on its South Slope.

In recent years, building materials and equipment denoted that one more restoration project was underway, similar to those undertaken at other sites on Athens’ Sacred Rock. But now the crane has been removed, the site restored, and Sunday walkers on the pedestrian street of Dionysiou Areopagitou are left wondering about the imposing monument that draws their gaze from its location above the Theater of Dionysus.

The tourists who reach the plateau with its enormous pine tree and informative signs learn the history of this unique monument which has adorned the Acropolis for 23 centuries. The Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos, as it is known, is impressive from whichever angle one looks at it. It was, after all, constructed to be seen by all of ancient Athens. Today it looms imposingly above the busy pedestrian streets of Areopagitou and Makrygianni, it transfixes one’s gaze from the Parthenon Gallery in the Acropolis Museum, it towers over you when looking at it from the Theater of Dionysus.

© K. Arvanitaki

The monument was first created circa 320 BC by Thrasyllos, a judge (agonothetai) in the Great Dionysia (a large ancient Athenian festival featuring theater competitions). It consisted of a marble facade in front of a large natural cave and was a form of a choragic monument – monuments created by sponsors to commemorate the awarding of prizes at the Great Dionysia. Three structural parts of it had survived in place, the rest had fallen to the ground. The monument collapsed after it was damaged by cannon fire in 1827 during the siege of the Acropolis by the Ottomans.

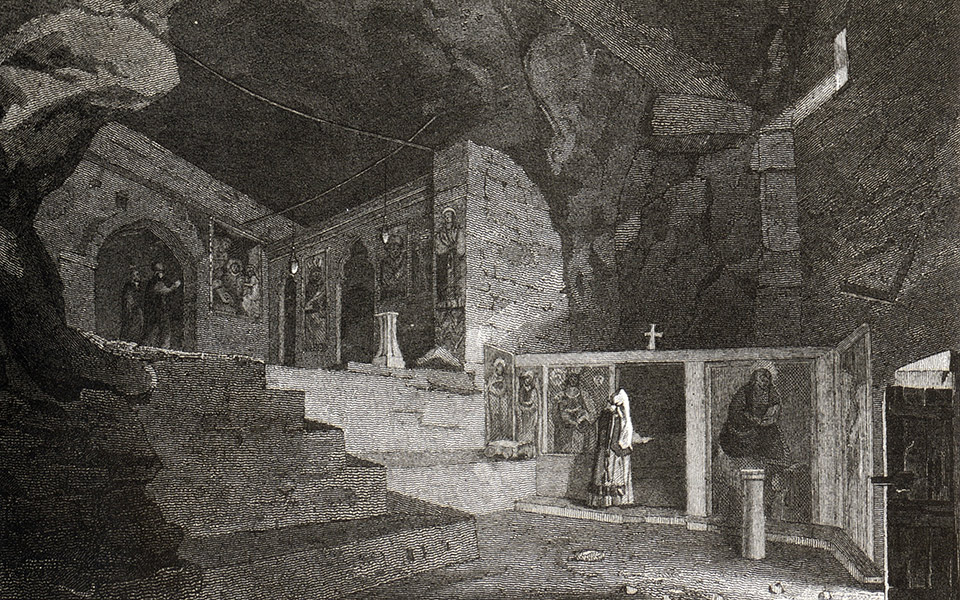

Today the metal railings indicate, in their own way, that there is something valuable inside. Older Athenians have heard of Panaghia I Spiliotissa (the Virgin Mary of the Cave) – the church which was created in the cave during the period of Ottoman rule. But most are surprised when they learn of the double history of the monument from the informative plaques.

Everyone, and particularly foreign visitors, want to get up close to the monument that combines both ancient and Christian elements. But the guard’s whistle prevents anyone from getting too close.

The Frescos

One sunny Friday, the architect-restorer of the monument, Konstantinos Boletis (a former president of the Scientific Committee for the Preservation of the Acropolis Southern Slope Monuments) took us inside – a truly one-of-a-kind experience. When the lock opens, an entire world is revealed. One fresco in front of us depicts a bishop and St. Spyridon; another wall features St John the Evangelist as well as a large representation of the Hospitality of Abraham with three seated angels. There are plexiglass installations to prevent the frescos from being damaged by the water that is dripping from the roof of the cave. In its depths there is an impressive marble icon depicting the Assumption of the Virgin Mary which has also been restored.

“The frescoes of Panaghia Spiliotissa include the best preserved examples of post-Byzantine iconography in the area of the Acropolis,” Boletis tells us. “After many years of research and restoration work by the Committee of the South Slope of the Acropolis and the Athens Ephorate of Antiquities, 190 years after its collapse due to Turkish bombardment on 1 February, 1827, the choragic monument of Thrasyllos is once again in dialogue with the rock above the Ancient Theater of Dionysus, enlightening us about the artistic and aesthetic value of the South Slope of the Acropolis.”

The Thrasyllos monument, which is dated by an inscription to 320/319 BC was modified in 270 BC by his son, Thrasykles. “Its facade, an almost exact copy of the west facade of the south wing of the Propylae of the Acropolis has the form of two door openings, with pilasters, a central pillar, a Doric architrave with continuous guttae, a frieze and a cornice. The frieze was decorated with ten olive wreaths, 5 on each side of a central ivy wreath, while above the cornice there were bases for the choragic tripods.”

After the construction of a small church in the cave, the monument was preserved almost intact until 1827 with some alterations, such as the blocking of its two openings with walls. And it was always a favored subject in the historical depictions of Athens’ monuments in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Boletis tells us that in a central location above the monument, many of these historical paintings depict a marble statue of Dionysus which had been placed there, most researchers agree, during the Roman era. This statue was removed in 1802 on behalf of Lord Elgin and is today on display at the British Museum. As for the Christian chapel behind the facade of the ancient monument, during the period of Ottoman rule it was visited by Athenians who would pray for the health of their sick children.

That said, this cave was also where adulteresses would be publicly shamed.

An Inspiration for Western Architecture

Following the establishment of the Greek state, the monument’s restoration was announced by the Archaeological Society, “however a large part of its stone was used for the restoration of the Byzantine Church of Panaghia Sotiras tou Nikodimou, better known as the Russian Church on Filellinon Street.” But what is important is the monument’s impact on western architecture. “When stone from the Thrassylos monument was transferred out of the area of the Theater of Dionysus like a common building material, ‘morphological borrowing’ from [the monument] had already rendered it a characteristic feature of the Greek Revival in Great Britain, via the depictions in the work The Antiquities of Athens by the British artists, J. Stuart and N. Revett.” The olive wreath, for example, was used as a decorative theme on many other buildings.

“In his analysis for the Schauspielhaus in Berlin, the great German architect, Karl Friedriech Schinkel, stated that it was a source of inspiration for his columns. Morphological elements ‘borrowed’ from the Thrassylos monument can be found in the Rotunda of the US Capitol Building and the Lincoln Memorial in Washington.”

The in-depth research for the monument’s restoration began in 2002. Konstantinos Boletis oversaw the implementation of the restoration plan, with the civil engineer Efrosyni Samba responsible for the structural aspects of the project. The funding of the project was marked by many ups and downs. Restoration work was restarted in 2011 funded by Structural Funds and the Program of Public Investment, while the project was completed by the Athens Ephorate of Antiquities. Four architects from the National Archaeological Museum were involved in the project, while a new frieze block with four wreaths was constructed, sponsored by the J. F. Costopoulos Foundation.

A changing city

“The restoration of the Thrasyllos monument has changed the area,” Eleni Banou says, the director of the Athens Ephorate of Antiquities. And she urges us to look at the city in a new light. “On the South Slope there is the Thrasyllos monument where the restoration of the ‘lost’ monument impresses visitors, but there is also the Asklepeion which is less visible – due to the tall trees; you can see it only if you take the path uphill. There is also the Klepsydra, which changed the landscape on the North Slope, while in the Roman Agora the interior of the Tower of the Winds is visitable for the first time, as is the Fethiye Mosque, one of the most impressive buildings of the Ottoman era in Athens which hosts low-key events such as the exhibition about Hadrian that we are preparing for mid-January.”

She says that visitors cannot enter the interior of the Thrassylos monument for safety reasons. “It is a difficult climb. We want to restore the stairs of the Theater of Dionysus. And neither has the walking route been entirely completed – that is also on the Ephorates program.”

All of these constitute new routes in the city, such as Aristotle’s Lyceum, a new archaeological site that was opened to the public a few years ago next to the Byzantine Museum. Monuments and sites that are “new destinations in the city.”